SAN FRANCISCO — Artists with shorter and less varied careers have been celebrated with retrospectives, so it’s hard to believe that an icon such as Judy Chicago has had to wait this long for her flowers. But that injustice makes the experience of seeing Judy Chicago: A Retrospective at San Francisco’s de Young Museum — the exhibition’s only venue — even more rewarding. This blockbuster show spanning six decades of the artist’s career may actually be worth the wait — it’s expansive and satisfying, leaving the viewer with much to think about.

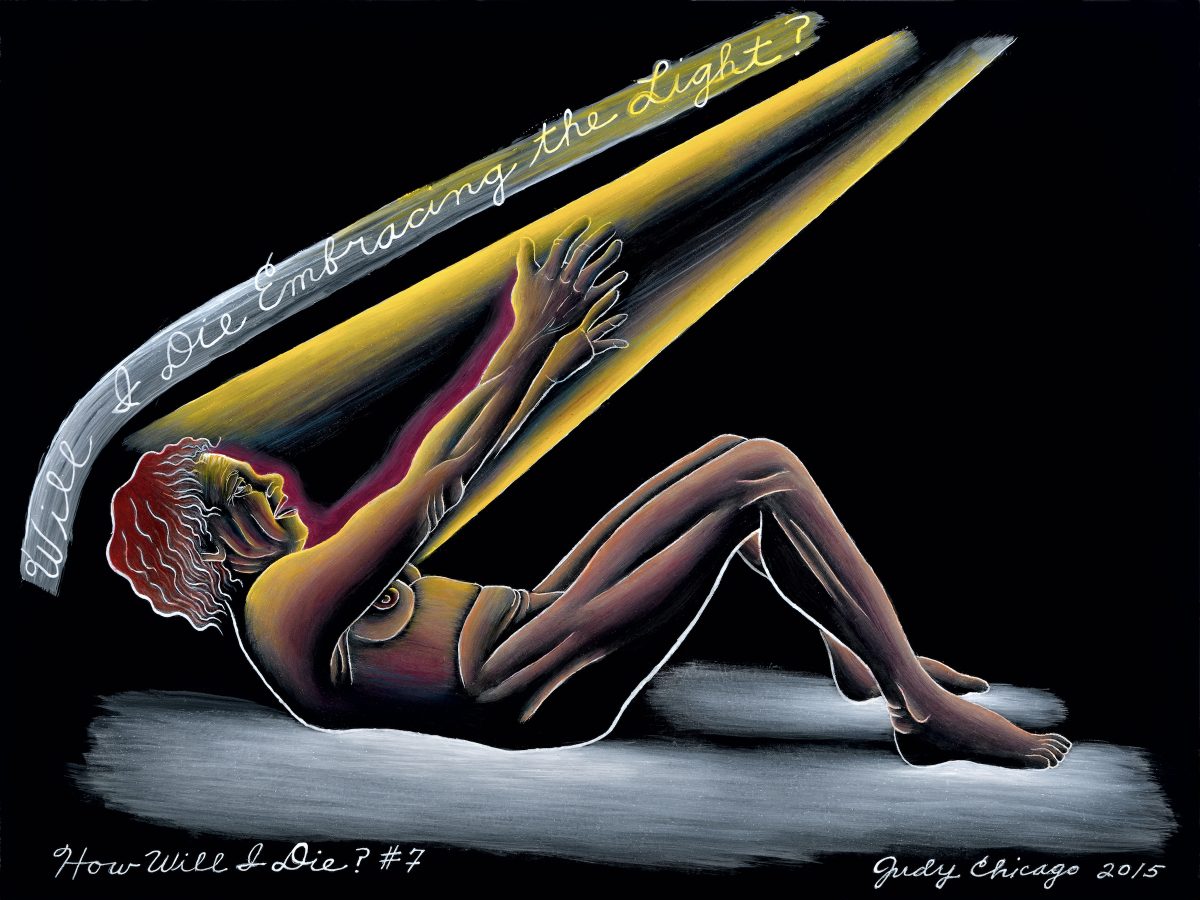

The exhibition, curated by Claudia Schmuckli, takes a unique approach by presenting Chicago’s work in reverse chronological order, with each room organized around a theme. The first room contains her most recent body of work, The End: A Meditation on Death and Extinction (2015-19). One is immediately confronted with “Mortality Relief” (2016), a life-size bronze relief depicting Chicago on her deathbed holding a bouquet of flowers. A series of small-scale, intimate paintings on black glass show Chicago’s meditations on death and dying in other cultures as well as a deeply personal sequence on “How Will I Die” that asks questions such as Will I die in my husband’s arms? Along the opposite wall are companion paintings in the same style on the theme of extinction, lamenting the destructive impact of humans on plant and animal species including rare orchids, endangered elephants, and sharks that are cruelly mutilated to harvest their fins. The parallel focus on her innermost fears — what will happen to me? — along with the most all-encompassing grief — what are we doing to the planet and other living things? — is both astute and incredibly moving.

Holocaust Project: From Darkness into Light (1985-1993) is a series of mostly paintings and sculptures and a tapestry mural representing the artist’s examination of her Jewish heritage and the atrocities of the Holocaust. This body of work culminates in a darkened room with black walls where a magnificent stained-glass piece, “Rainbow Shabbat” (1992), literally lights up the space with a vision of a more equitable world represented by diverse individuals seated together, heads turned towards a standing Mother Teresa-like figure at the head of the table.

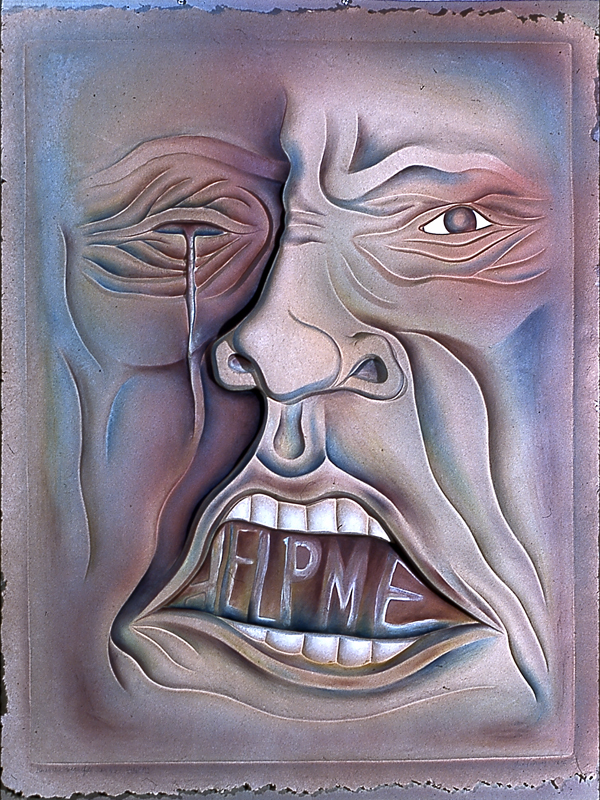

The huge canvases in the PowerPlay series (1982-87), exemplified by “Driving the World to Destruction” (1985), portray muscular male figures engaged in acts of aggression, subverting the classical beauty of Renaissance nudes by showing the ugliness of patriarchy and toxic masculinity.” Two paintings of oversized, square-jawed faces depict expressions of anguish with the words “Hold Me” and “Help Me” appearing in the figures’ open mouths like a silent wish to express vulnerability. Many of the paintings showcase Chicago’s trademark rainbow palette, but what’s truly striking is how relevant they are to the present moment and the lingering turmoil of the Trump presidency, even though these works were made more than 30 years ago.

No one can deny that Chicago tackles “big” topics like the environment and genocide, but paradoxically it’s her most intimate and personal work that comes across as universal. While her recent output reflects on the end of life, Birth Project(1980-85) contains some of her most famous artwork celebrating female bodies, the act of childbirth, and various creation myths. These tapestry and mixed-media works exemplify Chicago’s interest in elevating fringe techniques such as needlework and embroidery, often maligned as too domestic or feminine for serious art. Many of them were created collaboratively with women who specialized in needlepoint, weaving, and quilting.

It’s impossible to write about Judy Chicago without mentioning “The Dinner Party” (1974–79). This monumental installation — consisting of a large, triangular table adorned with intricate embroidery and 39 sculptural place settings named for important women in history such as Virginia Woolf, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Sojourner Truth, along with a tiled heritage floor inscribed with more than 900 additional names — was first exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art in 1979 and is now permanently housed at the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art at the Brooklyn Museum. While the installation itself is not included in the De Young exhibit, an entire section is devoted to a variety of “test plates” featuring suggestive floral and vaginal imagery that caused a huge sensation when first exhibited, plus sketches of some of the designs and a short film. The work is essential to an understanding of Chicago’s career and influences, although she has expressed her frustration that it tends to overshadow the rest of her oeuvre. Indeed, it was created more than 40 years — half her lifetime — ago.

Chicago’s work has been written about extensively, and more recent scholarship pays tribute to the breadth and ambition of her achievement while acknowledging shortcomings. She has said that she intentionally creates art that will be legible to mainstream viewers, eschewing the cool detachment and irony of postmodernism. That accessibility is both a blessing and a curse — it has the potential to reach a broader audience, but its literalness is also its downfall. For example, her effort to be inclusive with “The Dinner Party” by listing hundreds of women from history only served to highlight who was noticeably left out. There are only a handful of Black, Indigenous, and Latinx women, and no women at all from Asia, South Asia, or the Pacific Islands (unless you count the Hindu deity Kali). Notable women from the most populous region of the planet are completely absent. It’s a perfect example of the limitations of art with a social justice lens: The more noble the intention, the more harshly it will be judged.

The works featured in the “Feminist Art Project” section offer a fascinating glimpse into Chicago’s feminist awakening. There’s a memorable advertisement from a 1970 issue of Artforum in which the young artist, then known as Judy Gerowitz, publicly “divested” herself of the patriarchal convention of taking her father’s and then husband’s name in order to freely choose her own name: Judy Chicago. A short film documents “Womanhouse” (1972), a collaboration with Miriam Schapiro that was a house in Burbank, California filled with installations focused on conventionally female topics such as the body and domesticity made by Chicago and her art students as part of the feminist arts education program she established at Cal State Fresno, which later moved to California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). The work from this period is important as it marked her radicalization and subsequent focus on making art outside of — and often in opposition to — the male gaze. Although celebrated as one of the pioneers of feminist art, Chicago speaks candidly about being rejected by the male-dominated art establishment and the difficulty of forging her own path largely unsupported.

The final room in the exhibition presents Chicago’s earliest work under the theme of “Minimalism and Atmospheres,” which includes the large-scale sculpture “Rainbow Pickett” (1965, recreated 2004), groovy painted car hoods, and a playful series of lifesaver paintings and other minimalist compositions. Videos of her Atmospheres (smoke performances) play in the adjacent hallway.

Just outside the main exhibition space, past the museum gift shop, is a set of large banners in jewel tones hanging from the ceiling, on the theme of “What If Women Ruled the World?” It was unclear to me whether these were actually part of the retrospective — they are excluded from the catalogue and audio tour, and I had to ask museum staff for more information. The banners are from “The Female Divine,” a project commissioned by Dior for its 2020 spring couture show held at the Rodin Museum in Paris. My first thought was that the banners didn’t fit the overall narrative for the exhibit — one focused on Chicago’s outsider-ness and pursuit of a vision that was oblivious to trends and uncorrupted by the art market. The invitation to collaborate with a prestigious high fashion brand was “the greatest creative opportunity of my life,” according to Chicago, and perhaps a prelude to her recent resurgence. (In addition to the De Young retrospective, Chicago’s work is currently featured in at least two other Bay Area venues — an exhibit on art and feminism at the Berkeley Art Museum, and an exhibit focused on the lyrics of Leonard Cohen at the Contemporary Jewish Museum.) One can’t claim to be anti-fashion and then suddenly show up on a Dior runway.

But the more I thought about it, the pieces from “The Female Divine” provided a more fitting close to the exhibit than her early experiments with minimalism. They echo the utopian impulses of her most explicitly feminist work and bring us full circle back to the present. The banners speculate on what life might be like if women were in charge — Would God be female? Would men and women be equal? Would there be equal parenting? Would the earth be protected? — and they invite us to imagine a future that is better than the hyper-polarized, pandemic-ravaged world we live in today. With everything we’ve been through, it’s undeniably appealing to dream of being reborn into a society that’s less divided, less hostile to women, and more just for everyone. To me, Chicago is at her most powerful not when she shows us “what is,” but when she asks us, “what could be?”

Judy Chicago: A Retrospective continues at the de Young Museum (50 Hagiwara Tea Garden Drive, San Francisco) through January 9, 2022. The exhibition is curated by Claudia Schmuckli.

0 Commentaires