At its core, colonialism is an exercise in smoke and mirrors. The colonized subject becomes an object of state terror while historically, government agencies and the media have repackaged these imperial projects as “foreign aid,” giving way to more indirect neocolonial endeavors. Back home, the rhetoric remains the same; politicians’ fiery speeches continue to convince their domestic population that intervention abroad is in their best interest.

Public relations campaigns do much of the heavy lifting in manufacturing deceptive appeals to “peace” and “democracy,” and otherwise misleading through psychological operations (or psyops). During the Vietnam War, President Lyndon B. Johnson told wealthy business owners that “the ultimate victory will depend on the hearts and minds of the people who actually live out there,” as part of a counterrevolutionary strategy to suppress the Viet Minh army. He used the phrase “winning hearts and minds” in 28 public statements to sell the war.

Carriage Trade Gallery’s latest exhibition takes its name from Johnson’s now-infamous words. Curated in partnership with Rectangle, Brussels, Hearts and Minds brings together the works of 12 artists critiquing popular notions of economic nationalism and capitalist expansion. From Belgian colonialism in the Congo to the US occupation of Vietnam, the show analyzes how the spread of Western imperialism coincides with the history of deceit in the media.

A 1995 photograph of Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) embodies the typical burden of Western occupation. Vietnamese boaters float serenely in modest vessels before a barrage of gigantic corporate billboards — Xerox, Nestle, Carlsberg Beer, Nokia, among others. The corporate realm looms over the people in the foreground, as if threatening to overtake them. Photographer An-My Lê took this picture while visiting her hometown, which she fled during the war in 1975, and it begs the question of who these advertisements are for exactly.

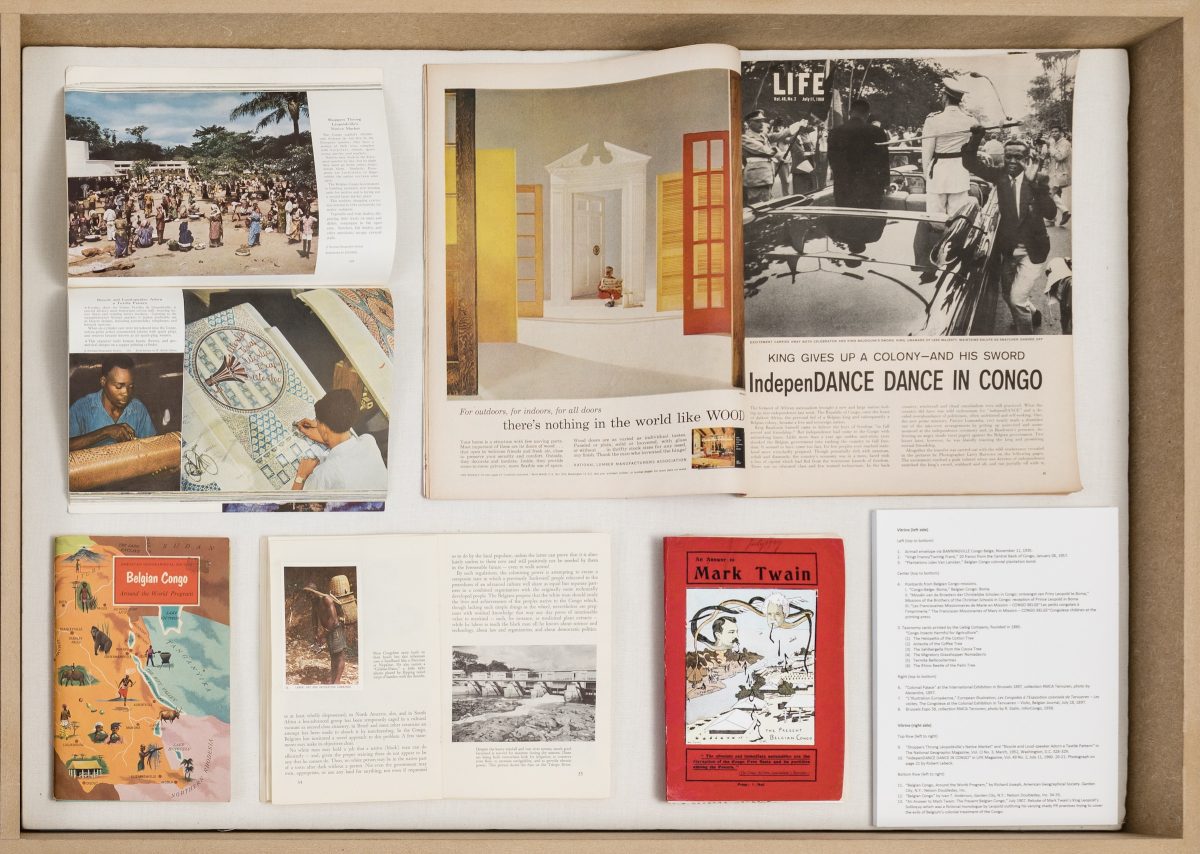

This narrative of disappearance and imposition continues across three rooms of the gallery, detailing how PR disguises imperial methods of social control. A vitrine displays 20th-century literature from various psy-ops and propaganda campaigns. US counterinsurgency leaflets, dropped over North Vietnam in the 1960s, appear alongside their English translations. Belgian posters from the 1950s promote mock villages that ensnared Congolese refugees — literally called “human zoos” — which were set up at the estate of King Leopold II and the 1958 World’s Fair. Above, Marina Pinsky’s photographs of the fingerprinting process add an overarching element of surveillance, linking the historic documents to the present.

The juxtaposition of archival materials unearths subtle contradictions even within a single booklet or magazine. An open issue of LIFE magazine shows a color advertisement for lumber, with a white child seated in a pristine home setting. On the next page, in black and white, a Congolese man has snatched the sabre off the Belgian King Baudouin, who remains unruffled, perched atop his motorcade in Leopoldville. Robert Lebeck took this photo one day before Congo legally achieved independence. (Just seven months later, Congo’s first democratically elected leader, Patrice Lumumba, would be assassinated with the help of the US and Belgium.)

“Although this independence of the Congo is being proclaimed today by agreement with Belgium, an amicable country, with which we are on equal terms, no Congolese will ever forget that independence was won in struggle, a persevering and inspired struggle carried on from day to day, a struggle, in which we were undaunted by privation or suffering and stinted neither strength nor blood,” Lumumba said on Independence Day.

Belgian director Chantal Akerman combatted 20th-century Cold War rhetoric by filming ordinary people in Russia, Poland, and Czechoslovakia after the Berlin Wall fell. The video plays in a dark room at the far corner of the gallery, allowing the work to loop uninterrupted. A mesmerizing compilation of romance and fraternity, From the East (D’Est) (1993) finds beauty in the mundane goings-on of people disappeared behind headlines. Meanwhile, in the present, billionaire-funded media campaigns continue to spread misleading propaganda about countries with histories of socialism, making it unclear where foreign policy ends and journalism begins.

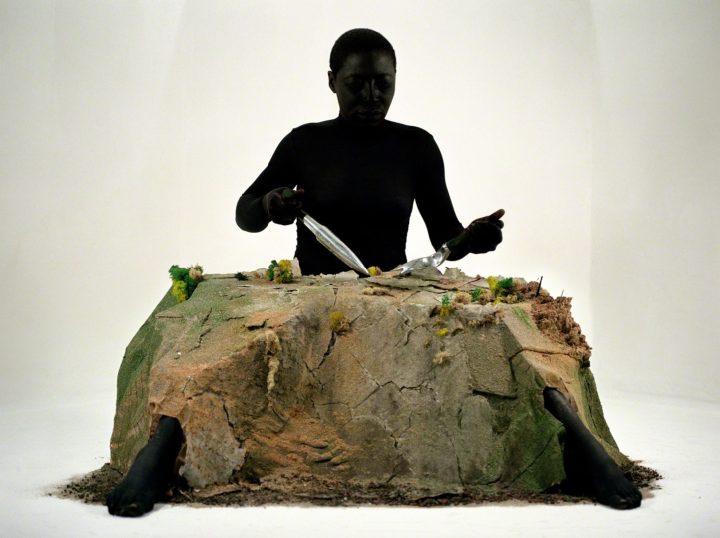

In Alterscapes : Playground (E) (2015), Nigerian conceptual artist Otobong Nkanga photographs herself seated with a landscape over her lap like a dinner table. She wields two large metal utensils to cut into the rocky terrain, alluding to British colonial endeavors in the oil-rich African country. Half a century later, Nkanga replicates the violent act like a sort of dystopian ritual. The scene is equally absurd and austere, making a folly of extractive violence while hinting at its long-term effects.

There is a common misconception that countries in the Global South are “developing,” when in reality, many of them are still recovering from centuries of imperial dominance. As Michael Parenti once said, “The most powerful ideologies are not those that prevail against all challengers but those that are never challenged because in their ubiquity they appear as nothing more than the unadorned truth.” Right now, a broad neoliberal coalition is consolidating through intersectional imperialism, using “woke” branding to whitewash abuses by government agencies, media outlets, universities, and museums. This is perhaps why politicians’ appeals to civility ring so hollow. But uprisings are spontaneous and, as Hearts and Minds reminds us, they can persist even in spite of the most expensive disinformation campaigns in history.

Hearts and Minds continues at Carriage Trade (277 Grand Street, 2nd Floor, Chinatown) through June 13, 2021. The exhibition is a joint project of the gallery and Rectangle, Brussels.

0 Commentaires