I research and write about the history of visual culture in Canada, ranging from mass-produced images to fine art, with my most recent work focusing on commercial tattooing from the late 19th century to the 1990s. My research sites are common to art historians and scholars of visual culture: museums, archives, and library special collections. More recently, I have found myself utilizing a far less familiar location: the court room (and, due to COVID-19, the digital court room). In the process, my methodological toolkit, which previously included archival research, visual analysis, and the examination of print media sources, has expanded to heavily rely on governmental access to information legislation, a method seldom used by humanities researchers and even less so by those who study images.

Starting on May 11, I will begin several related cases against the Ministry of Public Security, which oversees Quebec’s police force and medicolegal laboratory. Through this lab, the ministry legally owns (you read that right) dozens of human remains amassed from the bodies of murder victims, encompassing, among other things: skulls, bones, parts of human reproductive systems, and, what initially spurred my interest, tattooed skin. These items were accumulated by Quebec’s first forensic scientist, Dr. Wilfrid Derome, between roughly 1914 — when he opened the laboratory, the first of its kind in North America — and his death in 1931. In the late 1990s, Derome’s collection was transferred on loan to Quebec’s provincial history museum, the Museum of Civilization in Quebec City, where it still resides. Since then, the ministry and the museum have used items from this collection to cultivate Derome’s reputation, by way of museum exhibitions and publications, as a foremost figure in the development of forensic science in North America. He was that, but the narratives they have perpetuated do not provide a fulsome or historically accurate account of how this collection came to be.

My connection to this all began during 2016, after I noticed an image of an object from the museum’s collection on a federal government database: five pieces of tattooed skin affixed to a wooden plaque. These pieces of skin included one with a tattoo of an American flag alongside the initials “MB,” which Derome removed from the body of a murdered 29-year-old woman named Mildred Brown in 1929. I went to see this object when it was on public display in 2018, since the museum had denied my request to view it up close in their storage facilities. Afterward, I began inquiring about its provenance. One museum archivist relayed to me that there was an image of Mildred Brown on an autopsy table, albeit with tattoo still on her arm, in a sizeable scrapbook Derome maintained titled the album des causes célèbres or “album of famous cases.” Not only did the museum deny my request to access that as well but, within days of my inquiry, it pulled Brown’s tattoos from exhibition.

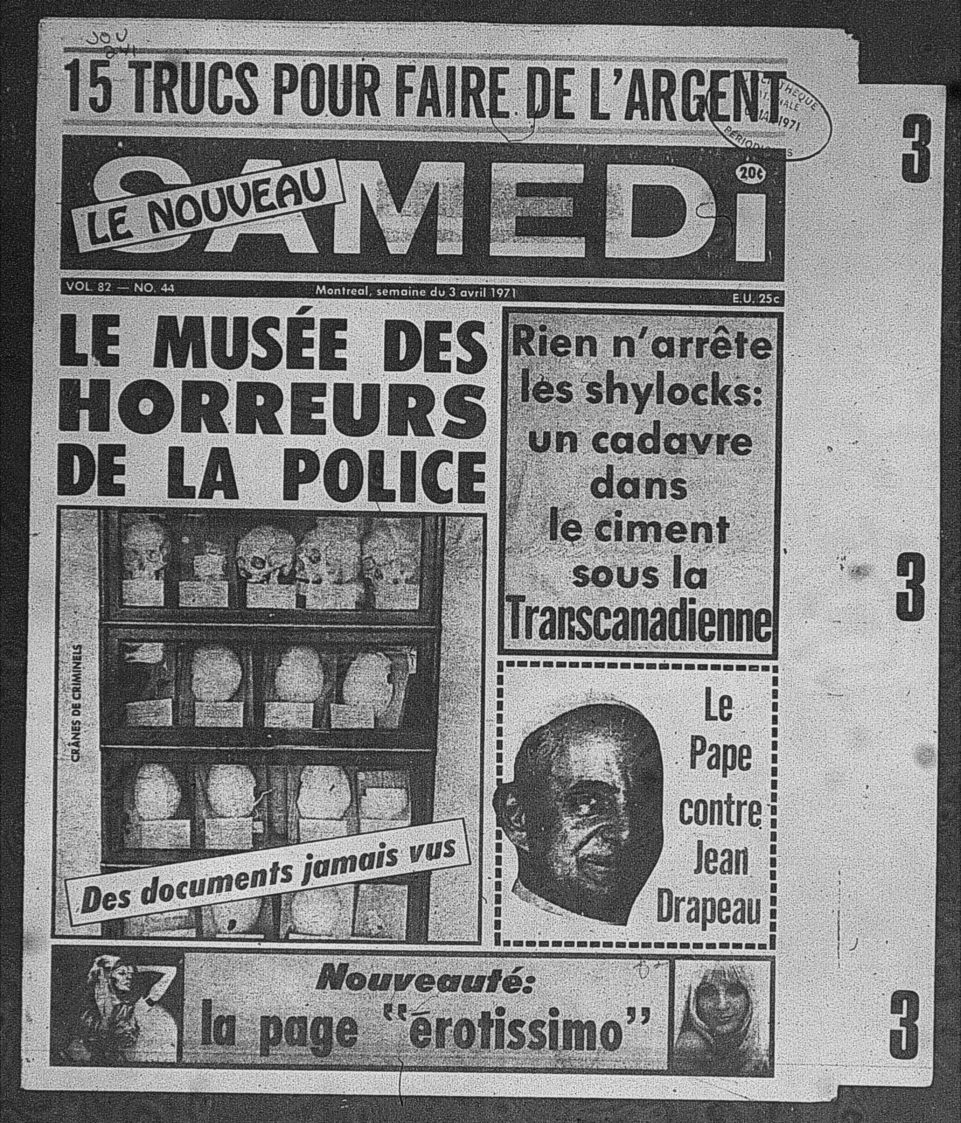

During the early 1970s, Derome’s collection was intended to form the basis of a publicly accessible institution called the Quebec Provincial Crime Museum. To generate interest in the planned museum, journalists from a number of Montreal-based outlets were permitted to view and publish images of the collection. Since then, our collective societal understanding of the ethical implications of museums not only collecting, but also displaying, human remains has shifted significantly toward community consultation and, when deemed appropriate, repatriation. The museum does not seem to have been privy to this message between its receiving of the collection in the late 1990s and my inquiries in 2018, instead repeatedly displaying remains from it up to the point when I began asking about their origin.

The stonewalling I faced from the museum necessitated a change in tactic, leading me to file several requests with the Ministry of Public Security — again, the owner of these objects — through Quebec’s provincial access to information legislation. In one case, I’ve requested the annual reports of Derome’s laboratory, which are documents listed on an archival inventory I obtained through a separate access to information request. According to the ministry, these documents do not exist. In another instance, I asked to access a number of remains, including the wooden plaque with Brown’s skin, as well as the collection’s archival component. The Ministère has denied that request on the grounds that it would significantly hinder the institution’s work — a common reason for denying an access to information request. During 2020, for example, the same court I will appear in ruled in my favor against the transportation agency that oversees Montreal’s metro system, which maintained that my request would encumber its work after I asked for images of graffiti applied to metro exteriors. Finally, in the case that started it all, I am requesting to view the aforementioned album des causes célèbres, which Wilfrid Derome’s biographer was given unfettered access to while carrying out research for a book that was conveniently funded by the Ministry of Public Security. Many of the “famous cases” featured in the album correspond to remains the museum currently holds on loan from the ministry, including the tattooed skin of Mildred Brown.

Discussing my initial informal requests to the museum, curator Sylvie Toupin wrote privately to her colleagues that access to the Derome collection should only be permitted for “serious (and historical) studies” and that staff should “be careful of voyeurism, and unhealthy curiosity.” Her statement begs the question: By whose and what criteria is this to be evaluated? Judging by its actions, the museum does not feel any sense of accountability to the families of those whose remains it holds in its storage facility. Rather, the museum’s behaviour suggests that the only stakeholder it feels responsible to is the Ministry of Public Security, which — as the name of its Montreal headquarters, the Wilfrid Derome Building, indicates — has a vested interest in presenting its institutional lineage in a positive light. And, as law enforcement responses to wrongdoing within its own ranks consistently show us, even when the proof is insurmountable — exemplified most recently by the frequent capture of police violent misconduct on video — these institutions tend to protect their own at almost all costs, in this instance 90 years after Derome’s death.

As a result of my experiences, I have become interested more generally in how public institutions restrict access to and try to conceal the existence of certain images, a topic I am in the early stages of writing a book in order to address the subject with a greater depth. From this perspective, whether I win or lose in these cases is less consequential — the museum and the ministry have already revealed both their motivations and the extensive resources they are willing to invest to hinder my work. What started as narrowly focused research has cascaded into a more impactful study on institutional ethics, revealing the legal, political, and policy implications that image control has. For the ministry and the museum, however, there is much at stake. Should the court rule in my favour, this will not only grant me access to these items but, by way of legal precedent, grant it to future researchers as well. Should that happen, the ministry will no longer be able to tightly control the institutional history of its own laboratory and the museum will not be able hinder the narrative about how it came to be in the possession of dozens of remains from homicide victims.

0 Commentaires