At 80, how many artists would paint a nude self-portrait with such honesty? The sagging skin, the warped shoulders, the droopy bosom and bulging belly pull no punches. Neel never painted herself young because, as she explained it, her agreeable appearance didn’t match her disagreeable and rebellious personality.

Born in 1900, the artist did what many young lefties once did, she became a communist. But unlike most of them, Neel stayed a communist. If only the Met Museum had dubbed this show: Alice Neel: America’s Premiere Communist Portraitist. But they settled for the gentler, more PR-palatable People Come First.

Why didn’t Alice Neel paint schlocky social realism like her fellow anti-capitalists? Probably because Neel couldn’t resist twisting portraiture’s conventions. She did more than document poor people, activists, and bohemians. In her stylistic choices, she coaxed portraiture into a candor that overrides its embellishing defaults. But it’s subtle. Whereas social realism hits us over the head, Neel alludes. She once equivocated, “Should thoughts be said plain, or [isn’t] it more fun to play hide and seek — to hide them artfully in little corners?” Look and read closely! Neel tucks surprises into her portraits’ details — nuances and backstories. The best approach to this retrospective is to examine a few works in detail.

No Warhol portrait contradicts his public image as much as Neel’s. At 42 in 1970, he looks more beleaguered than posh. Two years earlier, Valerie Solanas shot him. How did Neel get Warhol to reveal his scars and medically necessary corset? Small wonder he once remarked “Nudity is a threat to my existence.” Yet, Neel pierced the veil, portraying the pain and vulnerability behind the cool persona. It’s the most forthright portrait of Warhol ever done. Of course, it’s not considered the most iconic.

As a lifelong Marxist, Neel was deeply engaged in advocacy for people of color. At a panel in 1999 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Benny Andrews, a co-chairman of the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition claimed that she was one of just four white artists that joined BIPOC artists in the famous 1969 protests of the Met’s Harlem on My Mind show. How ironic Neel is now enjoying a posthumous retrospective at a museum she once protested. Her good intentions, however, did not always result in ethical portrayals of people of color and her uneven efforts offer a cautionary tale.

Right: Alice Neel, “James Farmer” 1964, oil on canvas, 43 3/4 x 30 1/4 inches

(both works © The Estate of Alice Neel)

At her best moments, Neel lionizes Civil Rights leaders and BIPOC luminaries, asking viewers to acknowledge their brilliance against the grain of hegemony. In her portrait of community organizer Mercedes Arroyo, the activist looks up, dreaming of possibilities. The Civil Rights leader James Farmer furrows his brow and gazes out with the intensity of moral clarity. In her portrait of the Black playwright and actor, “Alice Childress” (1950), the star looks away absorbed in her inner life. Since the Renaissance, portraiture has encoded genius with visages deep in thought. Neel challenged the viewers of her time — can you genuinely behold the scintillating intellects of people who happen not to be white?

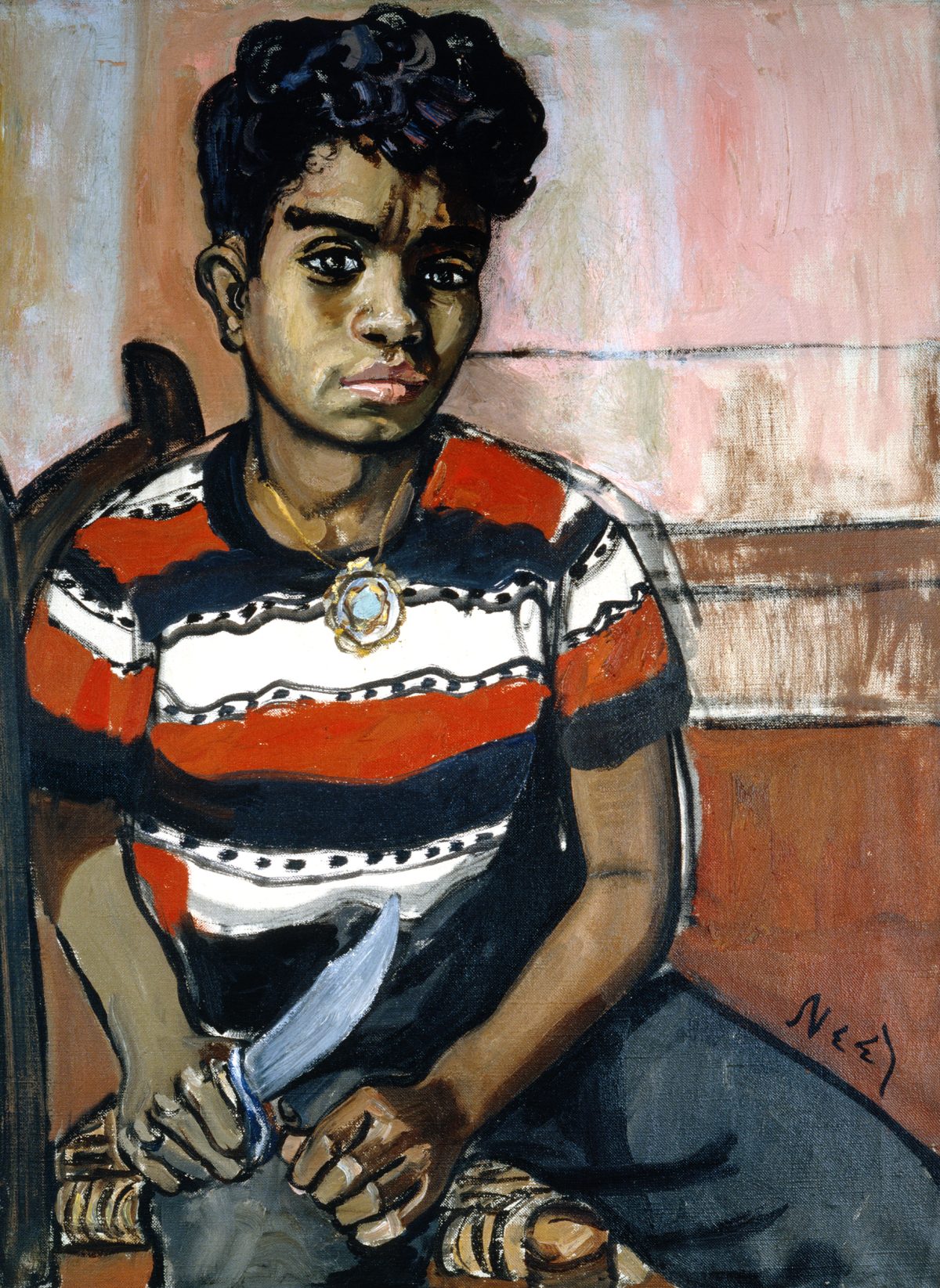

Right: Alice Neel, “Dominican Boys on 108th Street” 1955, oil on canvas, 41 7/8 x 48 1/16 inches

(both works © The Estate of Alice Neel)

On the other hand, Neel’s anonymous children of color paintings have not aged well. Despite her noble intentions to humanize individuals devalued by capitalism, they are too generic to be resonant. Where are the little details that allude to their unique personalities? The pathos of “poor children” hijacked her sensibilities. The works backfire because they deny the children’s individuality and reduce them to to racial types. Don’t their names belong in the titles instead of “Two Girls, Spanish Harlem” or “Dominican Boys on 108th Street”?

A recent article in the New York Times tells the story of Jeff Neal, who Alice Neel painted as a boy along with his now-deceased brother, Toby Neal. This exhibition reunited Jeff Neal with a portrait he hadn’t seen for decades and whose whereabouts were unknown to him. Something stinks in this process of a white woman painting the likenesses of two young men of color, selling it to someone else and then leaving the brothers in the dark for decades. (Further, this story didn’t emerge until after the catalog and wall tags were edited.) Can we admire what Neel got right, while also acknowledging what she and her collectors got wrong? Do artists and collectors have a responsibility to keep in touch with the individuals portrayed in works like this?

Neel did better in this haunting portrait of “Georgie Arce No. 2” (1955). The youth visited her several times when she lived in Spanish Harlem, sitting for portraits. He grips a knife and purses his lips defensively, while staring out vigilantly, anticipating threats. But there is a conflicting tenderness in the eyes as the shoulders safely relax. Is he play-acting? Is he showing his true colors? Neel once explained,

He had a rubber knife and used to pretend to cut my throat. This was just fun and games. He once said to me, “I don’t like to play.” He was a desperate little character, but why shouldn’t he have been desperate? When I lived in Spanish Harlem there were no Spanish teachers in those school and Spanish culture was completely suppressed.”

Why go generic, when complex portraits like Arce’s convey a child grappling with a mix of tenderness and rage as he navigates his identity and relates to society?

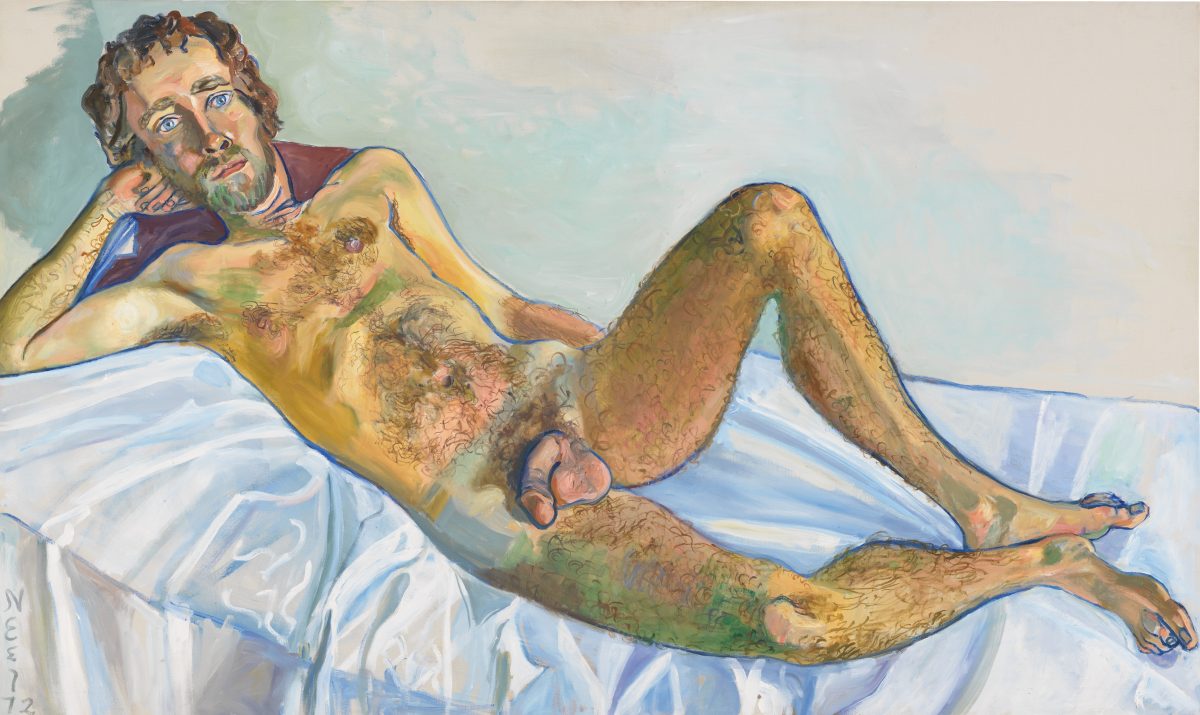

In the 1970s, artists recast the male nude with feminist and queer gazes. A young critic and curator, John Perreault was planning a show on the male nude’s new moment at the School of Visual Arts gallery. He wanted to include Alice Neel’s notorious 1930 painting of Joe Gould with three penises (also on view at the Met). In characteristic Neel form, the artist asked Perrault to pose nude for a second new painting for his show. Neel engaged with the male nude throughout her career, long before it was fashionable — everyone else was late to her party. People Come First includes many male nude images of her lovers, highlighting how groundbreaking it was for a woman like Neel to own her pleasure in her art, long before second wave feminisms valorized it.

Likewise, Neel’s pregnant female nudes turned the odalisque genre upside down. In works like “Pregnant Maria” (1964), Neel cherished painting every curve, the enlarged nipples, the swollen belly. As she once opined, “I feel as a subject it’s perfectly legitimate, and people out of false modesty, or being sissies never showed it.” Although, Neel participated in many feminist enterprises, she never renounced her Marxism and relished flouting feminist orthodoxies. She once observed “both men and women are wretched and it’s often a question of how much money you have rather than what your sex is.” In these pregnant nudes, she relinquished the class signals of fashion, focusing instead on the raw corporeal experience. By hanging several of these works in People Come First, alongside detailed wall texts, the curation does justice to the artist’s matchless interest.

Audre Lourde once mused “Only by learning to live in harmony with your contradictions can you keep it all afloat.” Alice Neel coaxed the staid genre of portraiture into revealing rather than concealing the contradictions of her sitter and her society. The real skill here is in the subtle harmony Neel achieved, which keeps each work afloat despite showing the hard stuff. These days, many portraits and selfies alike gloss over such inconvenient truths. Neel rightly refused sugarcoating.

Alice Neel: People Come First continues through August 1 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan). The exhibition was curated by Kelly Baum and Randall Griffey.

0 Commentaires