The painting “Rhubarb,” by the Norwegian artist Nikolai Astrup (1880–1928), depicts a woman picking that extravagant-looking plant in a spring garden high on a hill. The woman, Astrup’s wife, Engel, wears a delicate white dress with a pale blue print that fairly glows, much like the flowering fruit trees above, with the deep surrounding greens; a mountain streaked with glacial ice across the lake creates a high horizon line that presses the scene toward the front plane. The mood is quiet, suffused with the thin light of a northern night, and though the painting expresses a kind of reverence for Astrup’s wife and a nearby daughter, it is not sentimental. We may wonder why Engel wears so fancy a dress for such a mundane activity; she feels like kin to female protagonists in paintings by the Nabis, similarly embedded in pattern and color in a very different world.

The painting is dated 1912–21, which means, like many of his efforts, Astrup labored on it over a period of years. He did not produce with ease. In fact, he created just 250 paintings and 52 woodcuts during the course of his life, cut short by the respiratory ailments he suffered from the time he was a small boy. Like the rhubarb’s, his season was brief.

Astrup was a horticulturist as well as an artist, and he planted many varieties of rhubarb to harvest on his own farm, called Sandalstrap, on land across the lake from the garden where Engel is at work — that of his childhood home in Jølster, in rural western Norway. He painted the theme of a spring garden repeatedly throughout his life. Indeed, one of the strange sensations in visiting the first-ever North American survey of his work, Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway, on view at the Clark Art Institute through September 19, is a continuous deja vu in discovering this marvelous work yet noticing that the same themes recur in subtle variations, in a Groundhog Day chronology.

Curator MaryAnne Stevens has assembled a striking survey of nearly 100 works in which Astrup constantly revisited the parsonage where he was raised, the eldest of 14 children born to the local pastor; the gardens and buildings of Sandalstrap (now Astruptunet, a preserved site named for him), which he laboriously built on the inauspicious southern slopes of Lake Jølster from 1912 on; the bonfires set along the mountains on St. John’s eve; those local mountains, such as the giant, mounded Kollen, with its distinctive profile; fields of bright yellow marsh marigolds, threatened in Astrup’s lifetime by farm cultivation and drainage, but lighting up his penumbral greens and blues as surely as Engel’s dress.

Those flowers were mostly gone by the time they were painted: Astrup’s work is as much about memory as observation. It is a point made more than once by the authors of the excellent catalogue, including Karl Ove Knausgård, master of memory, who originally published the short “Prelude” in the current volume less than a decade ago, on the occasion of a visit to his mother in Jølster. “Everything we could see,” he wrote, “Astrup had painted.”

Norwegians indeed know and esteem Astrup, but he is barely known in the United States. Everyone has heard of his elder contemporary, Edvard Munch, who collected works by Astrup. Curious that there is not a hint of psychological trauma in Astrup’s paintings and prints, despite the parallels in his own experience to Munch’s hardships, including illnesses that took the lives of siblings and eventually his own. He and Engel had eight children, and we see a couple of the little girls dressed in red, harvesting something from the floor of a beech grove with flowering foxglove in several paintings and prints. Unlike Paul Gauguin, Astrup seemed to harbor a real affection for his large family and a true obsession with his home region. He might have chafed in letters against the philistinism of Jølster, but he lived there always; it was the wellspring of his creative life, to which he returned after training in Kristiania (now Oslo), and making repeated and sometimes extended visits abroad, including to Berlin, Paris, and London, studying and admiring art that was all the rage.

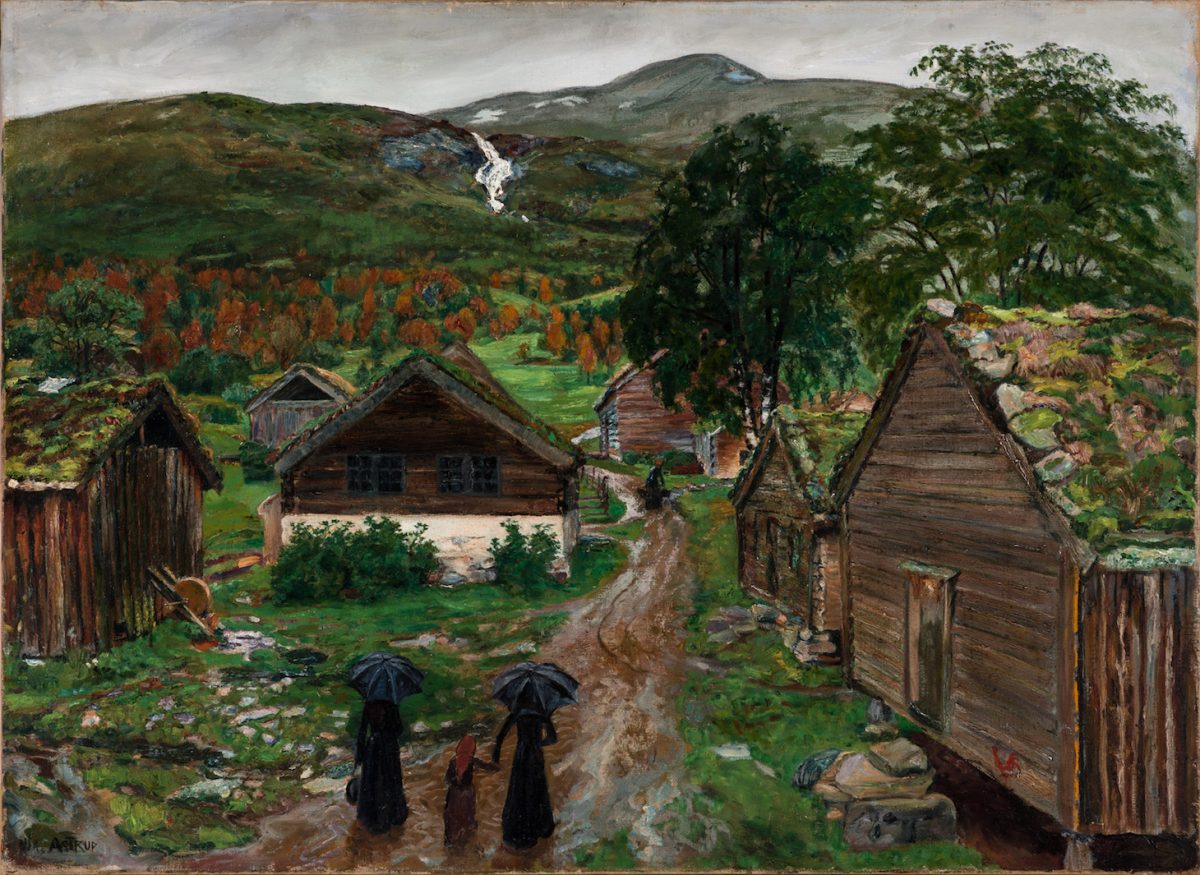

Though perfectly capable of the kind of naturalistic painting that characterized a previous generation of Norwegian artists, Astrup preferred to explore the tropes of modernism — the flattening, the odd perspectives and exaggerated palettes, the patterning — which he wielded with a folksy, almost naïve execution. A hero was Henri Rousseau, and that influence is evident in works like “Funeral Day in Jølster” (1908), an early painting, with its spare line of mourners following a pastor through a landscape colored in what Astrup called his “poisonous greens.” He would have been all too familiar with such processions, as living conditions hastened mortality in Jølster.

Yet his letters include fond memories of picking berries on the thatched roof of the drafty house that doomed his health, a subtle mixture of danger and beauty that also permeates his work. A goose and girl in the flowering night garden in “Night Light, Rhubarb, Goose, and Bird Cherry Tree” (c. 1927) are northern kin to Rousseau’s monkeys and lions in the tropics — with the difference that Astrup’s subjects were actually observed, if inflected and enhanced by memory. Astrup discovered authenticity close to home. His patterned interiors and simplified figures recall painters like Denis, whom he would have seen at the Salon des Indépendants. Astrup was not alone, of course, in marrying an “authentic” national and local voice with modernist aesthetics; such was the mission of countless late 19th- and early 20th-century culturati across Europe, not least his countrymen Edvard Grieg and Henrik Ibsen.

I teach the history of print, but I had not previously heard of Astrup, who, as it turns out, was as inventive as Munch in his exploration of woodcut. As an artist’s medium, woodcut experienced a revival only in the late 19th century. Astrup’s extraordinary prints were never issued as uniform editions and, like his paintings, were often produced over long periods of time, sometimes as commissions years after they were initially carved and impressed. Like so many European artists, Astrup was blown away by the Japanese ukiyo-e woodcuts flooding the markets by the time he first traveled outside Norway in 1902, and the influence of Hokusai and Hiroshige can be seen in his raking perspectives and varying chroma of identical scenes. Like Astrup, Gauguin similarly resisted the notion of consistency in his radical prints.

Astrup used oil-based inks which, unlike Japanese water-based inks, took ages to dry, though, as in ukiyo-e, he printed separate colors from separate blocks carved with the same scene. “Bird on a Stone,” a 1905 composition printed in versions, and displayed along with its woodblock matrices, has a vertical format common in many Japanese prints; the lakeside view is partially screened in the foreground by branches, a device commonly found in prints by Hiroshige. In four versions of “A Night in June in the Garden,” the dome-shaped Kollen presents various degrees of a rose-colored tint that recalls Hokusai’s Mt. Fuji at sunset. Astrup would go back and forth between the same scene in prints and paintings; such is the case with his glorious “Marsh Marigold Night,” a sweeping view of the valley with shadowy mountains surmounted by a gray-red sky, executed in both mediums.

After centuries of quasi-colonial subjugation to Denmark (mostly) and Sweden, Norway became fully independent only in 1905, and artists were engaged in helping to discover and build a national identity based on “authentic” local and regional characteristics. In this, there was an interesting nationalistic twist to Astrup’s use of wood. He lived at a time when Norwegian wooden stave churches were being restored after their wholesale destruction in the 18th century. Viking ships were being excavated. Norwegian mythology gave a prominent role to an ash tree that linked three concentric realms, one of which was inhabited by trolls, and logs were still the preferred building technique in this timber-rich country. With links to many contemporary writers and intellectuals, Astrup was conscious of playing a role in the (re)constitution of his nation’s culture, and his woodcuts are part of that effort.

Astrup’s father forbade his children from participating in midsummer festivities, with their drinking and dancing and roots in the pagan past, but as an adult Astrup celebrated such events in his paintings and prints. He cultivated native species in his gardens and built notched houses. He grew up reading Norwegian folk tales that had been collected in the decades before his birth and published with illustrations by Erik Werenskiold (1855–1935), an artist he admired, with captions like “The Trolls had only one eye among them, and they took turns using it.” In a few of the paintings and prints on view, a goblin is formed by the silhouette of a pollarded tree (e.g., “A Morning in March,” 1920); “Grain Poles”(1920) shows crops drying on tall supports that form a floppy regiment of figures with human faces, spirits of the valley. Toward the end of his life, Astrup painted such magical scenes alongside intimate views of interiors decorated with local textiles — two realms, one haunted and the other cozy, testimony to the paradoxes of a revelatory career.

Nikolai Astrup: Visions of Norway continues at the Clark Art Institute (225 South Street, Williamstown, Massachusetts) through September 19.

0 Commentaires