LONDON — Revolutionaries come in two varieties: the short-lived and the long-lived. The long-lived give themselves ample opportunity to recant. What exactly happened to Eileen Agar, one of England’s most celebrated Surrealists, who lived to be just a few years short of an entire century, and whose career as a painter lasted for seven decades?

She was born in 1899 in the sepia tones of Queen Victoria’s England and died in the cold light of 1991. We call her an English painter because she lived much of her life in England, but in fact she was born in Buenos Aires, into a family of great wealth. England claimed her very young. Her spirit of rebelliousness caused her parents to send her to private schools in England at the age of six or perhaps seven — far too young, anyway — in order to knock some sense into her. Those schools failed the parents, badly. Eileen fought back, and then went on fighting. She could not bear the idea of being presented at court as one of those swoony debutantes who hang limply off the arm of a man. In fact, she survived long enough as a fighting spirit for this posthumous retrospective to call her by the name of one of her best-known works: the Angel of Anarchy.

That’s a marvelously pithy and punchy title, so much better than many of the works that it encompasses.

Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy at the Whitechapel Gallery is huge, far too big for its own good: although Agar was a fine and inventive artist, she was never a great one. In fact, to put it in a nutshell, the works suffer from a certain emotional thinness. The show never plumbs the depths. In spite of the fact that it is full of arcane symbols and rebellious gestures, much re-working of Greek myths (which always promises to be more than a nod in the direction of profundity), and many creative exercises that seem to be nothing more than willfully self-conscious dallyings with obscurity, it never quite excites you enough. In fact, it bores when it is spread over so many acres of wall space.

What goes wrong then? She uses much color, but she seldom comes across as a great and instinctive colorist. The colors hang together with a degree of reluctance. Images coalesce, but without much conviction.

The show also suffers badly from some maddening tics of exhibition-making, which make looking at it in great detail an often frustrating experience. Many of the works of art come with individual wall texts, all quite small, which are placed below the paintings. I found that placing to be maddening, requiring repeated physical jerks — sharp knee bends and deep lowerings of the body — for me to see them. What is more, the texts are often too long and the font size too small — they are an effort to read.

They are also repetitious. You will find, as you move from one to another, that you are reading the same information over and over again, perhaps expressed slightly differently, as if their writers have assumed that you suffer from short-term memory loss (which is not necessarily the case for all members of the press). Works of art are described with a great and laborsome exactingness, as if we cannot really be trusted to draw our own conclusions. In fact, there is so much information handed to us on a plate that we risk completely forgetting what we ourselves might be thinking about, were we ever free to be independent beings coming fresh to a painting.

After all those schools failed to rein in her natural spirit of rebellion, Eileen shaved her head and took herself off to Cornwall, where wild spirits often flocked and nested and copulated with gleeful abandon during the 20th century. Then she went off to the Slade School in London to study painting, but the teaching was too conservative by half. Her self portrait of 1927, displayed against an exciting stretch of bright red-panel wall, looks robust and fierce, as if she is hying her way to a destination of her own choosing.

Where would that be exactly?

During a trip to Paris in the 1920s, she met André Breton and Paul Éluard, who told her that she was a Surrealist. Could that really be true? The feverishness of Surrealism’s spirit of disobedience, its sensuality and irrationality, appealed to her. Yes, she quite liked the idea of being one of those, though she could never quite fathom how painting could be an expression of the unconscious. How could anyone really know what a faithful expression of the unconscious would really look like?

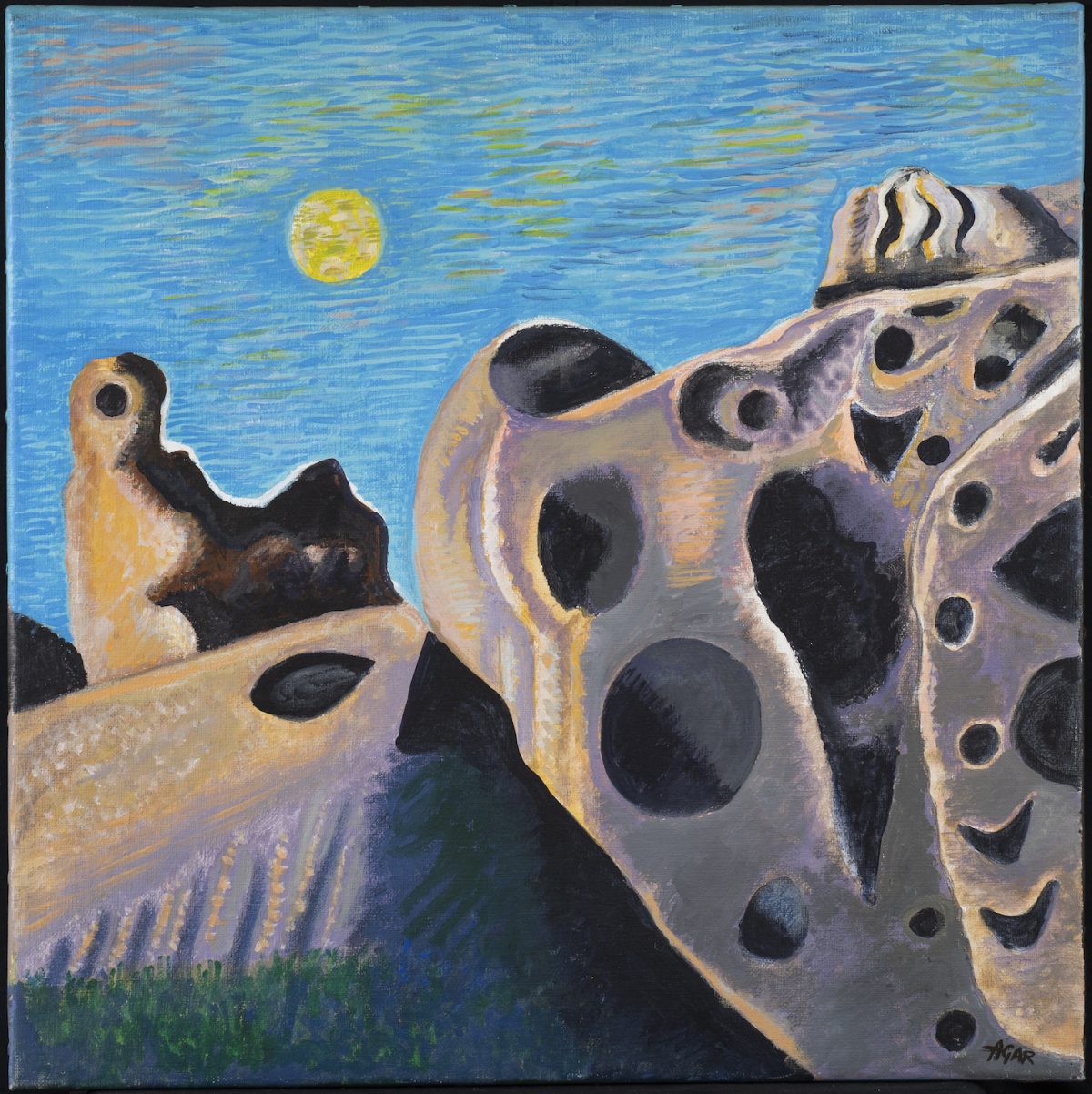

Agar was especially fond of marine life, the murky floatingness and driftingness of it all, how all those oddly shaped and seemingly unrelated thingies are forever bumping into each other, or staring at each other on the seabed for at least a millennia, with more than a degree of mild-mannered malevolence. Perhaps the look of marine life, and the way it behaved, may be as close as it gets to the idea of the Unconscious? Discuss.

This show makes much of the fact that she was a bit of a Cubist too, but then provides scant evidence for that bold assertion.

In later life, she reprised old themes and images (shells, birds, fossils, hands) and discovered the joy of acrylics. There is a freer play about much of this later work. The colors in “The Bird” (1969) are pure Tropics.

She had mutated into a bit of a songbird by the end, a gentler and less fierce phenomenon altogether. Recanting? Not exactly, but somewhat akin …

Eileen Agar: Angel of Anarchy continues at Whitechapel Gallery (77-82 Whitechapel High St., London, England) through August 29.

0 Commentaires