What strikes me most about Pat Adams, whom I visited at her Bennington, Vermont home, is her deeply appreciative nature. She communicates a sense of gratitude for a life in art, for her teachers, her family, and being a mother. This appreciation, it seems, is what allows her to truly see the beauty in the earth and nature, through layers of complication, chaos, and everyday labor. Connected to this is her consciousness of privilege. Adams recognized, in our conversation, her grandparents’ labor — working relatively barren land in Montana — but also the injustice that this land was taken from the Blackfoot Indians.

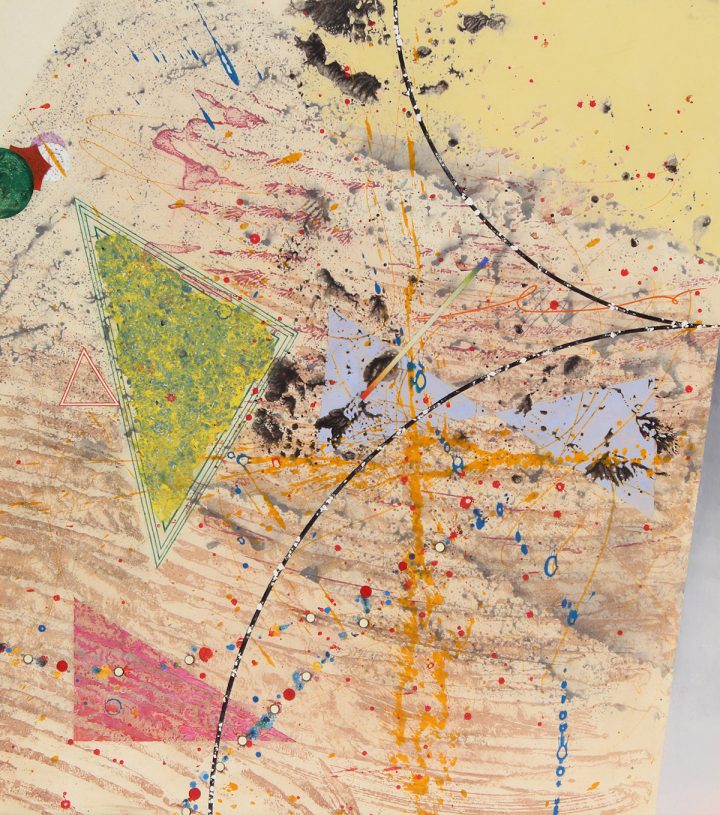

Adams’s abstract paintings are embedded with these layers. They include elegant arabesques and undulations, perfect circles, diamonds and star shapes. However, they also have networks of scrawled looping marks atop their ground. Adams incorporates grit into her paintings: mica, crushed eggshells, mother-of-pearl, and sand. This grit both sparkles and encrusts her surfaces. Recurring marks form pathways. They trace circles and record history: the steps others have taken on the same land, the markings they have left. The paintings reflect time in contemplation, and allow many forms, elements, and sensual experiences to gather, rather than one specific moment or place.

These collections and gatherings are physically present in Adams’s home and studio, where one sees tables and walls covered with fossils, shells, wood, cut fabrics, jars of pigments, grit and binder, shards of cut paper, quick sketches, clippings of art reproductions marked with diagrammatic notations, and stacks of records near a turntable.

Adams was born in Stockton, California, in 1928. She received a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1949, and also studied at the California College of Arts and Crafts and the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1950, she moved to New York City and enrolled in the art program at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. She taught at Bennington College from 1964 to 1993, and served as Visiting Professor of Art in Yale University’s Master of Fine Arts program from 1990 to 1994. Adams had 20 solo exhibitions at the Zabriskie Gallery between 1954 and 1997. Her work is represented by Alexandre Gallery, where she is the subject of a presentation at the Independent Art Show from September 9–12, 2021. A solo exhibition of Adams’s work will be held in the spring of 2022 at Alexandre’s new space at 291 Grand Street, New York.

Jennifer Samet: Can you tell me about formative experiences with art from your childhood? I know that you have connected your experiences fishing with your father to some of your compositional ideas about painting.

Pat Adams: I grew up in Stockton, California. It is a port 70 miles inland. Fishing was a weekend family activity. Stockton has wonderful channels; in that area, two rivers came together and created a delta. The earth there was so rich that the San Joaquin Valley was a magnificent agricultural center. We all ate all the different kinds of fish. In fact, in those days, there my dad could go to a stream with a fishing tool called a gaff, reach over a bridge, and bring out a big salmon. What was important to me was looking, as we sat on the banks of the river, to watch the fronds of a Tule plant twist and arc in the wind or bend under the weight of a red-winged blackbird. It was so quiet.

My grandmother lived with us, and thank goodness, she was there to support my interest in art. She gave me a full adult painting set when I was 12. Her mother painted, and I have one of her paintings. They loved art, and they all played the piano. They were living in the most godforsaken area in Montana at the end of the 19th century. Making something out of nothing, and being inventive, was something that came to me from both sides of my family. If you find a piece of string, you’re going to make something out of it.

I could take my bicycle and go down to the Haggin Museum in Stockton. I saw paintings when I was 10 years old. In that little museum are two paintings by James Baker Pyne, who was Turner’s only student. When, later on, I saw Turner in the Tate, I thought, I know who this is. It was one of the very fortunate things that occurred in my life.

Another one was being taken by my history teacher to see the opening ceremony of the United Nations at the Opera House in San Francisco, in the spring of 1945. The idea of one world — E. Pluribus, Unum, one of many — was a tremendous influence on me. The two atomic bombs were dropped that summer.

JS: You studied at the University of California, Berkeley. Who were some of your meaningful teachers?

PA: The faculty I studied with at Berkeley all studied with Hans Hofmann. I experienced a kind of proto-formalism in the art courses I took there. Therefore, I already knew about these ideas before I came to Bennington College, where Clement Greenberg had strong ties.

The person I loved working with was Max Beckmann, for just two months before he died. I studied with him at the Brooklyn Museum Art School in New York. He was a lovely fellow. He hardly spoke English; his wife would come around and talk. He would stand and draw over your work. That’s how he taught. What I learned from him was the wonderful concentration in how he would stand. You felt it was coming from his feet. We would walk and talk together after class; I remember us standing over the subway vent across from the Brooklyn Museum, because it was warm there.

I always had wonderful teachers. You should never underestimate luck. It’s probably the most incredible thing that happens, fortuna [good fortune] matched with sapienza [wisdom].

Every summer between university semesters at Berkeley, I would go to some place, like the Art Institute of Chicago, to study painting. But I also loved political science, anthropology, paleontology, and physics. I have these interests which I feel have fed my imagination. The imagination synthesizes all of our capacities. It picks up our sensibility, our feeling, our knowledge.

JS: Can you tell me more specifically about how the sciences have fed your work and your ideas?

PA: Everything I took from is really about the beginning. Physics is about the atom, which is two pieces of dirt hitting each other, Lucretius says. That is how the planets started. To watch how form modulates over time, and how time changes forms, is compelling. It helps formulate certain questions. My subject matter has been led by questions, wondering how things begin. My subject matter is qualities intrinsic to form.

I’m not a scholar, so I don’t really follow through the entire investigation. I come across a little thing, and think about it. That’s why I use the word “quiddities” to refer to the things I pick up and have an interest in, which may not have a name. I have a collection of these “what-nesses.” These bits and pieces, out of context, are fractured, like a little shard. But as they collect, they turn into forms that I want to use. For example, undulation is something that has mesmerized me forever.

JS: Albert Barnes’s text, The Art of Painting, was significant to you. You were introduced to it by your Berkeley professor Margaret O’Hagan. What do you appreciate about this book?

PA: The Art of Painting was absolutely formative. Barnes was a chemist, so he thought of the formal components: color, shape, and line, as he did in chemistry. They were like carbon, nitrogen, and helium. That was such a lucid parallel; I think he was marvelously important.

JS: You made small-scale work in the 1950s and ’60s, a time when monumental paintings were championed. I wondered if this was connected to your interest in American visionary painters like Ralph Albert Blakelock and Albert Pinkham Ryder.

PA: I really like my small works most of all. I didn’t start making large paintings until the late 1960s, after I had moved to Bennington, and had the time, space, and money. But I think my interest in smaller-scale work may have been inspired by seeing the Lindisfarne Gospel manuscript in London, on a trip to Europe in 1951–52.

I was traveling so much that I had to work in a small size to fit into my suitcase and wooden paintbox. And the year I worked at home in Stockton, I worked in the laundry room on one of the trays over the sink. Also, I loved Quattrocento Italian painting. In 1948, I had spent a summer at the Art Institute of Chicago, where there was a corridor of Quattrocento paintings. The question of size as a topic was never of interest to me. I was thinking about the materials I had at hand, how I would pack my work and get it back to the studio.

JS: Was it during this early 1950s trip to London that you saw J.M.W. Turner’s paintings? What interests you, specifically, about Turner’s work?

PA: Yes, on the way home from Italy, we stopped at the Prado before going to London. I saw Hieronymus Bosch’s “Garden of Earthly Delights” (1490–1500), which really knocked me out, because of the punctuation of very sharp little shapes in white, blue, red, and black on a field of tertiary color. That influenced me. Of course, Joan Miró comes out of that. In London, we saw Turner’s paintings and watercolors. What I love is that when you look at the open glazes, nothing occurs except the slow shift of pink and orange — an amount and placement determined in relation to the format.

JS: How did your work start to evolve technically during your time in Bennington?

PA: In the 1960s I saw a show of Maurice Prendergast’s monoprints. I loved the withdrawal of the paint. I went home and got a 4 by 8 piece of Masonite and I painted on that, and then flipped it over and pressed it onto canvas. A loaded brush can be excellent in some ways, but very limiting in others. In the early 1970s, I had a student whose father worked at Chemfab. She brought me a 4 by 8 piece of a flexible material that was coated in Teflon. It was a good surface: I could paint on it; I could easily flip it, and imprint it. I have many different techniques that I can employ in painting.

The idea of moveable walls came to me from Angelo Ippolito. I met him early in the 1950s and went to his studio. He had an independent wall. When I came to Bennington, I had the carpenter here make me a moveable wall. The wall could also be brought down flat to the floor so that I could do things like imprint dust pigment, blot with ink, and then bring the painting back up. Large canvases started at the end of the 1960s and the ’70s.

I have the most marvelous situation here in Bennington, although I miss New York terribly. My experience in New York was really very brief, but what was grand about it was I always felt I was a New Yorker because of [art dealer] Virginia Zabriskie. We were so close, and like two girls going through a lot. I would stay with her when I went into the city. Somehow I never felt that I had moved to Bennington. But here I am. A family person. A citizen of this community. I taught here for 30 years. But in my mind, I’m really a one-worlder type.

JS: Yes, I know you continued to travel a lot; how did this impact you and your work?

PA: My second husband was a colleague of mine, Arnold Ricks, who was a history professor here at Bennington College. In 1973, we took off with my two sons on a four-month trip through Egypt, Iran, Turkey, and all of Europe. My friends all laughed and said, “You’re taking a man who’s not had children, who’s not been married before, with two adolescent boys.” They, however, were unaware that my sons, Matt and Jase, had asked me if we could take Arnold with us on my sabbatical.

As I run around to different places, I’ve been confirmed in how solid Homo Sapiens is. We all want similar things. A little while ago I came across the Sanskrit word for many-sidedness: anekantavada. We are all trying to reach truth. We have to listen to whatever we hear. We may disagree with it, but there could be an aspect of truth that can help us form an idea.

JS: You have studied connections between art and neuroscience. Can you tell me more about these ideas?

PA: Neuroscientists are continuing to determine that there are fixed locations in the brain waiting for stimulation. That is fascinating. As an artist, I have a strong sense of want. It’s not that I myself want. It is almost that there are certain things outside myself that are awaiting to be told, awaiting to be said, awaiting to be exercised.

Our physiology, for our health, wants to have the pleasure and engagement with experiences that only occur in dance, in music, in the arts. The climate is increasingly removing people from that kind of experience. Art experience is substituted by spectacle. It would be wonderful if we could start over again and let people know the great pleasures of texture, for instance. Paintings pose and solve questions that relate to our daily encounters. How much? What position? What is proportionate? When you look at a painting, you see those things exercised, so that you have a chance to experience all of those concerns safely, and with a happy ending.

I always wonder why in the world we have something like art, and flowers. It must have a survival benefit. Homeostasis is about equilibrium and wellbeing. Painting, by arriving at a sense of balance, is giving us the stability that we need to be able to continue. We are so concerned with social issues right now — which we do need to be concerned with. However, I don’t think that is art’s only role. We don’t respond to images of destruction with the sort of equilibrium that we need.

JS: Your work often explores recurrence and repetition. Why is that?

PA: It is one of the desires, when you think about music and dance, the making of a mark, the sense of beat, repetition, occurrence, interval. I think those elements of my work may reflect that I studied music and dance for 10 years as a child. You see this recurrence in nature, you feel it as you walk. The beats of a drummer in a marching procession are so moving. They settle everything down and allow us to contemplate, commune.

JS: How is the scientific concept of Just Noticeable Difference (JND) relevant to how you think about painting? I think about how two similar forms may overlap or intersect in your painting.

PA: I have taken this theory and pulled it out of context. It is the difference threshold: the minimum level of stimulation that a person can detect 50 percent of the time. When I came across JND, I thought it was a marvelous thing — to recognize distinctions. Recognizing similarity and difference is not only essential to navigate the world, but also essential to savor experience. That kind of exactitude, that kind of acuity, is necessary to really see and enjoy the richness out there before us.

If you simply glimpse something, recognize it, and give it a name, it is over. It is a very different experience from dwelling and noticing of what it consists. The New York Times recently published an article about the Black ceramicist David Drake. He made gorgeous dark pots. I couldn’t stop looking at them. That is marvelous. It holds you and you stay with it, and you try, but may never come up with a verbal, rational discussion of what that force was. I hope that everyone has that experience of being held by something, of having to question their own understanding.

Something that concerns me greatly is what I call the “visual transaction”: what goes on between the painter and the viewer. What are the steps of perception that need to take place so that the viewer gets to the point where they can reflect upon what has been released in their imagination?

JS: Can you tell me how your paintings begin?

PA: They start with an impulse. Sometimes I’ll just make a couple marks, or I’m remembering a particular blue. Then I may put the paper aside. Other times I may go a little bit further. Of course, when I work larger, I have to know more what I’m doing, and plan. But generally, I feel that I’m looking into the unknown.

Stockton, where I grew up, has a great deal of fog. You wait on a corner for a bus, and you just see white; there is nothing. Suddenly something starts to emerge. Painting is a little bit like that. I know that I am wanting, but I don’t know what it is. I just start and I add onto. The works continue to evolve. I never know where the end will be.

One of the things I like about painting is that you don’t know. The artist must have a willingness to not know, to have the tolerance and patience to await. Emergence is so important. It’s important that artists not return to the Renaissance where they were given the topics and subject matter. I think we need to provide evidence. Artists who sit and work quietly are allowing themselves to come into it. They are providing evidence of our species: what impels us, who we are, what we are, what we do, what we are thinking.

0 Commentaires