CHICAGO — When people think of comics, they typically think of New York, the historic home of the US comics industry. They might think of comic book legends like Stan Lee and Jack Kirby or the ubiquity of New York in superhero comics and movies. Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now, now on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art, makes a case for including Chicago in discussions of how the comics industry, massive and varied, has developed to this day. The show includes the work of major creators who were born, lived, and/or worked in the city such as Daniel Clowes of Ghost World, Nick Drnaso of Sabrina, and cartoonist Lynda Barry.

Integral to the show is its highlighting of the contributions of Black cartoonists who published their work in the Chicago Defender, Jet, and other Black Media outlets, and whose work has not received the same amount of attention as their white counterparts. In the first gallery, between framed newspaper panels of the comic adventures of Dick Tracy and Brenda Starr, display cases showcase Jackie Ormes’s Patty-Jo ‘n’ Ginger and Joy Jackson’s Home Folks and Bungleton Green. Just off the room is a space dedicated to Charles Johnson’s one panel comics, known as gag cartoons, that satirized US race relations. Initially published in his first book Black Humor, they were later redrawn in 2020 (presumably for the exhibition).

Further along in the galleries, the exhibition showcases the work of Seitu Hayden, specifically his comic Waliku, published in the Chicago Defender in the 1970s. In contrast to Johnson’s gag cartoons, Hayden’s works are narrative comics dealing with more realistic depictions of Black life with stories from the perspectives of kids, covering topics from bullies and teachers, to holidays.

The show’s greatest strength is in the sheer diversity of styles, themes, and subject matter. It’s illuminating to be able to compare original drawings with the printed versions of comics, such as with Nicole Hollander’s Sylvia drawings and their finished print versions.

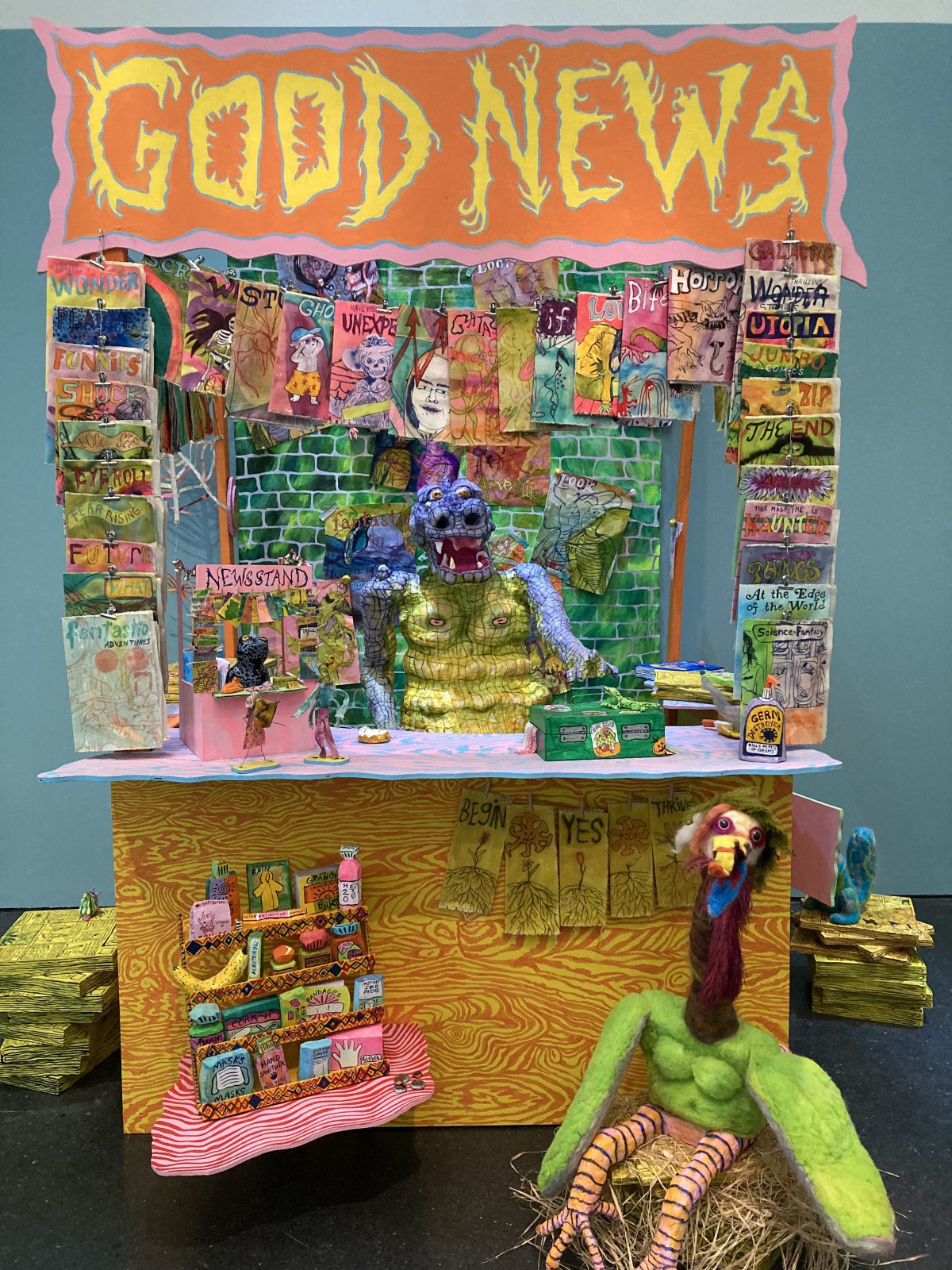

In addition to printed comics and drawings, the curators have assembled paintings, sculptures and installations from the artists themselves. Even the layout of the show — with its blown up comic book panels and covers, and comic-themed wall paint and door frames — makes the audience feel like they are walking through a comic book.

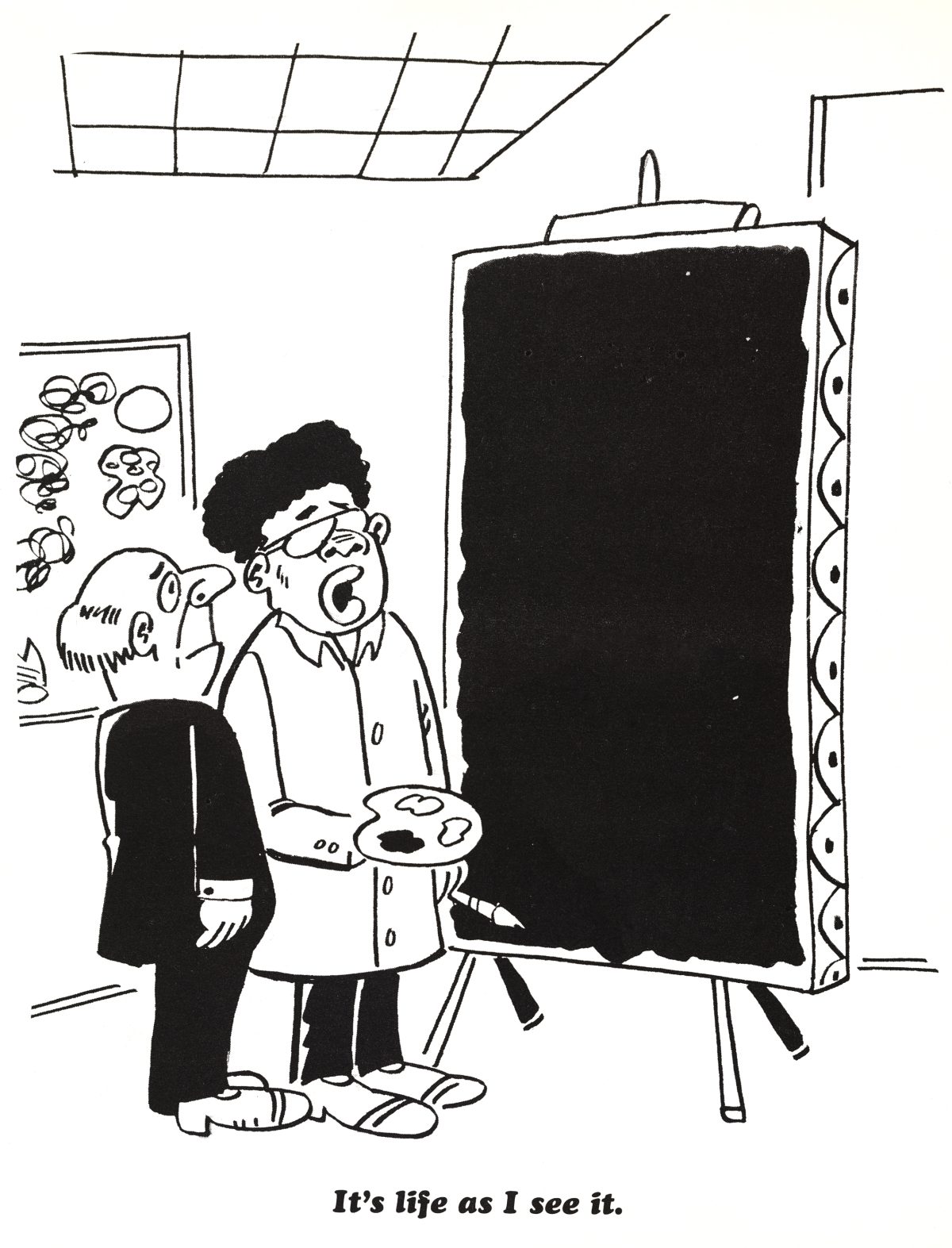

3D creations, including Kerry James Marshall’s models and dolls made in preparation for Rythm Mastr, are particular standouts here. Presented in glass cases, the models sit in front of mounted panels of the work, for which Marshall used the color black as his background, rendering details in white and inverting the traditional process of making comics.

Emil Ferris fans will be rewarded with original colored pencil drawings from My Favorite Things are Monsters as well as new acrylic paintings of bright and beautiful monsters — the artist’s signature work. A mixed media altarpiece including found objects like Virgin Mary statues and religious icons bears details added by Ferris, like a Godzilla statue or painted teeth and eyes. Large orange flowers bestow the feel of an ofrenda. Two large flanking paintings,of a beheaded Pope and a Sainted Werewolf, show off Ferris’s particular sense of humor.

Showcasing the breadth and depth of local creators, Chicago Comics affirms the rightful place of the city in the world of independent and newspaper comics.

Chicago Comics: 1960s to Now continues at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (220 E Chicago Ave, Chicago) through October 3. The exhibition was curated by Dan Nadel and organized for the MCA with Michael Darling and Jack Schneider. A related exhibition CHICAGO: Where Comics Came to Life (1880-1960) can be seen at the Chicago Cultural Center, and is curated by Chris Ware and Tim Samuelson.

0 Commentaires