LONDON — In 1971, Jean Dubuffet took over a disused factory in the suburbs of Paris and set his assistants to work on fabricating the hundreds of props that make up his colossal “living painting,” “Coucou Bazar.” Two years later, the outlandish, abstracted figures, painted in red, white, and blue with thick black outlines, appeared in an hour-long performance during Dubuffet’s retrospective at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. A selection of them is now on display in the Barbican Art Gallery’s current show, Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty — the first major exhibition on the artist since the Guggenheim’s in 1973.

The title of the piece — “Coucou Bazar ” — roughly translates as “Hi there, bazaar.” This could be an address to the exhibition itself: brought together, Dubuffet’s works create the atmosphere of a bustling, noisy marketplace. They teem with half-glimpsed slogans and faces, from his early lithographs featuring graffiti-like messages scrawled onto newspaper, to his late collages, made of fragments of colorful reused paintings. A mid-career series, Paris Circus (1961 – 62), brings to life frantic Parisian streets and claustrophobic restaurant interiors.

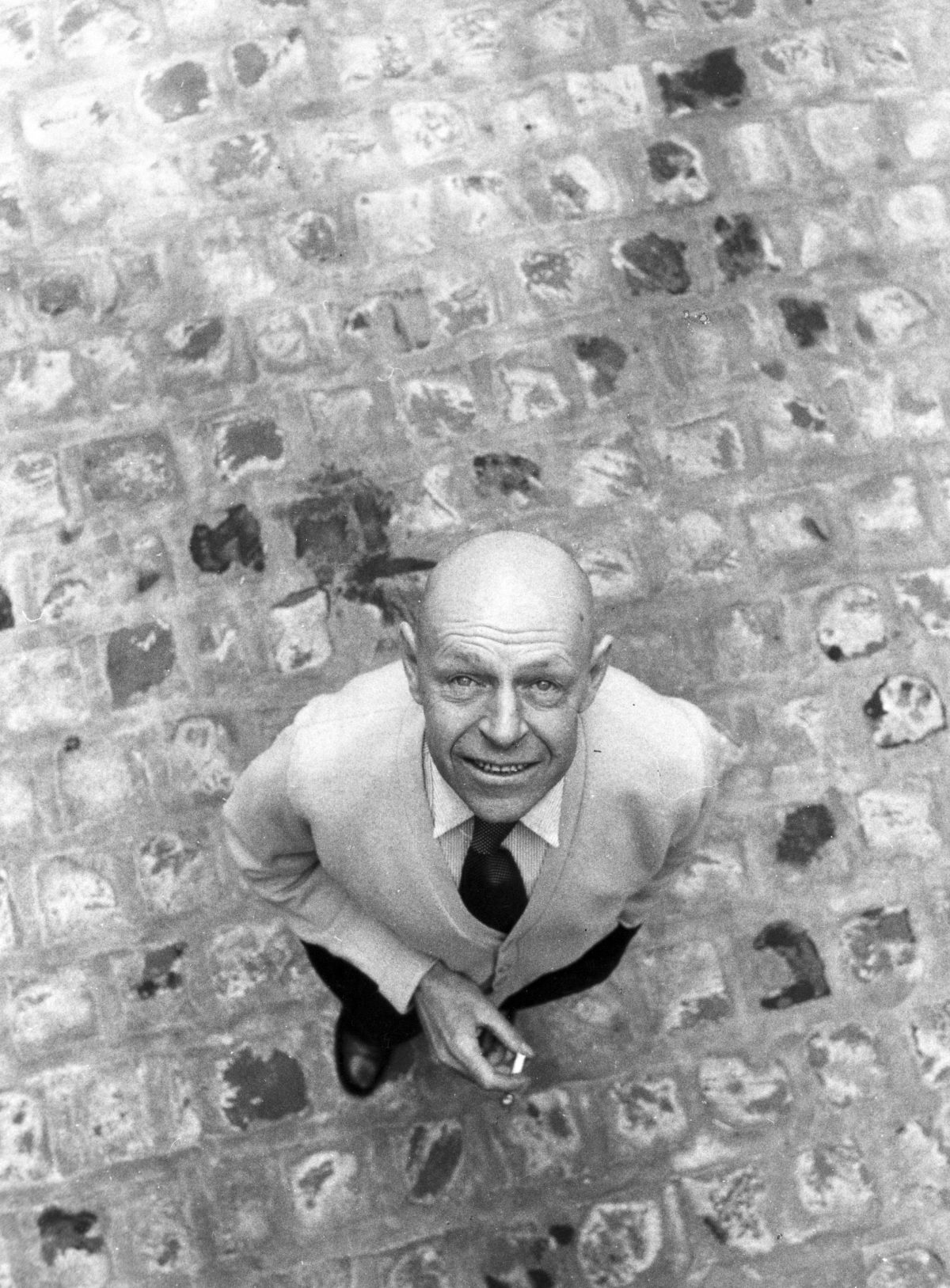

Born in 1901 in Le Havre, Dubuffet only seriously turned to art-making at age 41. As though making up for lost time, he experimented tirelessly with materials, using his studio as a type of laboratory. Some of his best known — and most controversial — works, which he called his hautes pâtes (“thick pastes”), were made from paint mixed with dust, sand, coal, asphalt, string, and glass. When these paintings were exhibited in Paris in 1946, visitors were horrified. A critic announced the birth of a new movement to succeed Dadaism: le cacaïsme. However, Dubuffet’s use of such materials was not just a provocation; it was ideological.

Dubuffet was fervently committed to breaking down distinctions between so-called “high” and “low” art and to challenging what he termed the “specious notion of beauty” passed down from classical art. This commitment lay at the root of his invention of art brut (literally “raw art”) which included the work of tattooists, autodidacts, mediums, psychiatric patients and the incarcerated. Two rooms in the Barbican’s show are devoted to works from Dubuffet’s vast collection of art brut (now housed in a dedicated museum in Lausanne, Switzerland), by artists such as Madge Gill, Laure Pigeon, and Miguel Hernandez — a particular highlight of the exhibition.

Curiously, Dubuffet’s anti-hierarchical approach to art did not translate to similar views on society. Though he claimed to be apolitical — as he once said, “I refrain from any political action because I understand nothing about politics” — he expressed sympathy with Nazi ideas, which he claimed possessed “exciting poetic virtues.” His correspondence is filled with unapologetic anti-Semitism: in a letter to his New York dealer Pierre Matisse in 1950, for example, he wrote, proudly: “I am becoming more and more anti-Semitic.”

The difficulty of reconciling Dubuffet’s anti-Semitic views with his significance as an artist might explain the relative absence of exhibitions on his work. Retrospectives have an inherently hagiographic nature and, when they are curated with a biographical focus, it is difficult to separate celebration of the art from celebration of the individual. The Barbican show presents the facts of Dubuffet’s life in a detailed timeline and doesn’t shy away from mentioning his Nazi sympathies; visitors are left to draw their own conclusions. But do the artist’s abhorrent views colour the way we see his art?

For me, as a Jewish person, the awareness of Dubuffet’s anti-Semitism inescapably affects the way I experience his work. Looking at his swarming metropolitan scenes and portraits of small, strange-looking people, I necessarily think of the anti-Semitic tropes that proliferate in his writing. I cannot escape the fact that — while I may admire Dubuffet for his continual experimentation with materials, his democratic attitude towards art-making, his talent, skill, originality and sense of humor — he would see me through the lens of his racially prejudiced worldview. The creation of art does not happen in a vacuum and nor does its reception. This is the paradox at the heart of exhibitions which focus in such depth on an artist’s biography and context: exploring all aspects of an individual’s creative self also means confronting potentially ugly aspects of their lives. And visitors, who bring their own views, experiences and identities, will of course be influenced by these in their encounters with the art.

Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty continues through August 22 at the Barbican Centre (Silk Street, London, EC2Y 8DS). The exhibition is curated by Eleanor Nairne.

0 Commentaires