Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s photographs flood Hales Gallery with the serenity and intimacy of the late queer Yoruba artist’s infinite lifeworlds. Tranquility of Communion immerses the viewer in Fani-Kayode’s potent aura, a follow-up act to the 2018 exhibition Rage & Desire. The soul-stirring photographs blend Yoruba cosmologies, queer desire, and Baroque theatricality — mirroring the artist’s multiplicity of cultural influences as a gay man who left Nigeria for England as a child. These works were created between 1987 and 1989 during the final years of Fani-Kayode’s short yet monumental life, amid the doom of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and its grave impact on the artist’s community. Still, each Black male figure is a beaming light against a darkly lit atmosphere — fusing spirituality and pleasure to represent the abundant glow of Black queer life.

In “Nothing to Lose IX (Bodies of Experience)” (1989/2021), a beguiling African mask stares fiercely. The mask represents the Yoruba trickster god, Eshu, who is both benevolent and mischievous — a parallel disposition to the figure kneeling below in reverence, clad in kinky leather and slyly hiding his face behind his knee. In “Adebiyi” (1990), the Eshu mask appears again, softly held near the face of a majestic figure crowned with flora. The mask itself evokes the ritual of Nigeria’s Egungun masquerade, in which the presence of the orishas and ancestors are summoned. The figure’s quiet poise reveals his devout admiration for the mask that facilitates communion between the living and the dead.

Nearby, in “Nothing to Lose XIII (Bodies of Experience)” (1989/2021), a Black man is adorned with ceremonial leaves, affirming his royalty. While kingly metaphors are often speculative in contemporary art, Fani-Kayode was indeed from an aristocratic family in Lagos. Although he lived in diaspora after 1966 when his family fled the Nigerian civil war, he maintained spiritual connections to his homeland. Throughout Fani-Kayode’s work, the use of Yoruba symbolism expresses a deep, vivid reverence for African spirituality. Nearby, in “Nothing to Lose XIII (Bodies of Experience)” (1989/2021), a Black man is adorned with ceremonial leaves, affirming his royalty. While kingly metaphors are often speculative in contemporary art, Fani-Kayode was indeed from an aristocratic family in Lagos.

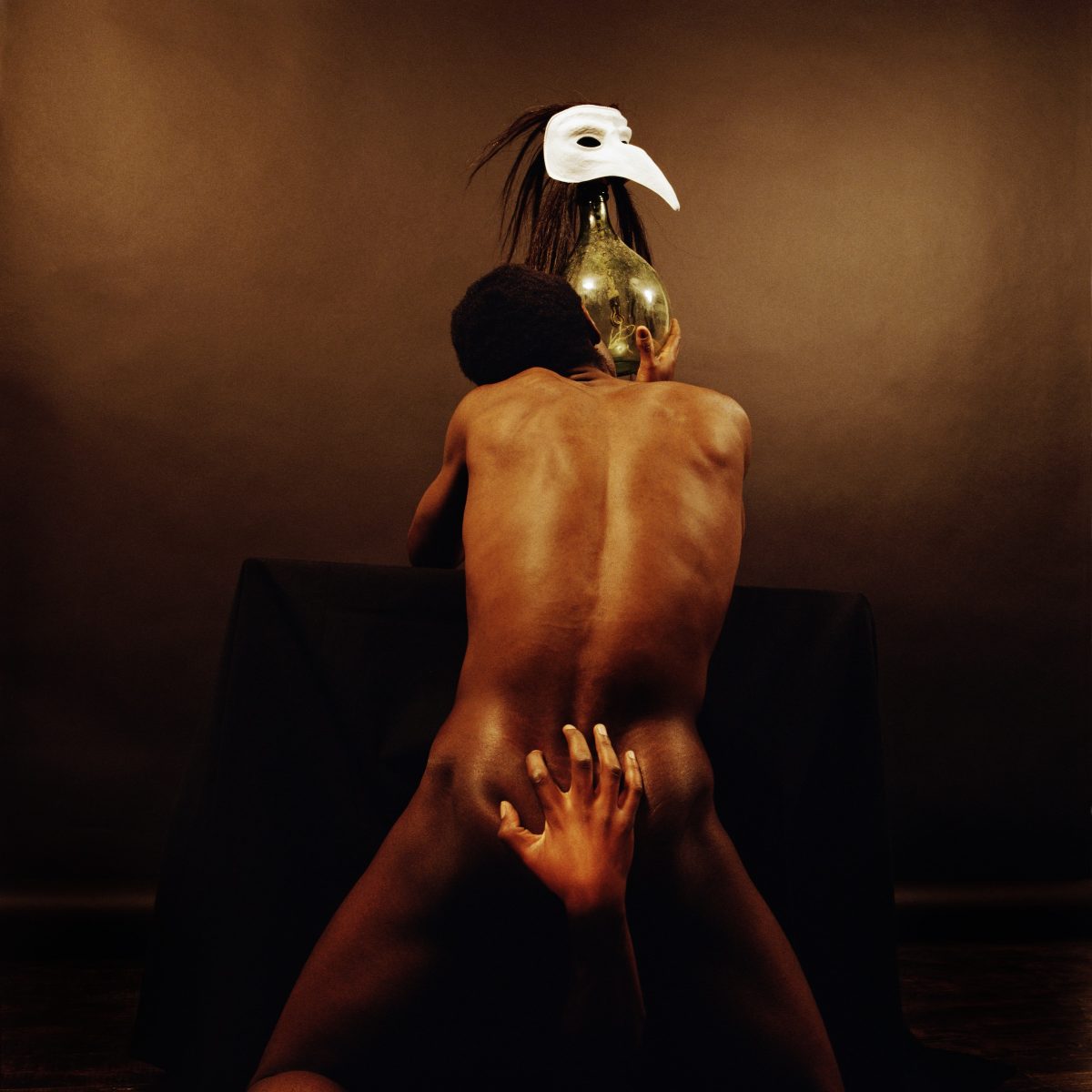

The exhibition’s titular focus, stemming from Fani-Kayode’s 1988 essay, “Traces of Ecstasy,” imbues a sense of stillness. Each figure transports the viewer back to the devastation and creation of the late ’80s, when erotic touch was laced with heightened risk for queer Black men in Thatcherite Britain and beyond. A photograph of a suggestive embrace is aptly titled “Every Moment Counts (Ecstatic Antibodies),” (1987–1988/2021). Above the nude figure is another reference to African religiosity — a regal bird mask symbolizing eiye ororo (“bird of the head”) that represents the power of the mind in Yoruba cosmology.

Gathered together, these photographs, and the spirited beings within them, emphasize Fani-Kayode’s attention to the holy, carnal, and political. Made just before his own death from AIDS complications, they illuminate the radiance of Black diasporic spiritual and erotic life, in spite of their precarity.

Rotimi Fani-Kayode: Tranquility of Communion continues at Hales New York (547 West 20th Street, Chelsea) through July 31.

0 Commentaires