In the final weeks of May 1871, French president Adolphe Thiers ordered soldiers to lay waste to the Paris Commune, resulting in massacres across the city. Seven days of repression by the bourgeois government culminated with the Versailles army executing the remaining Communards against a stone wall of Père Lachaise Cemetery. More than 20,000 Parisians were killed during La semaine sanglante (or Bloody Week), and 45,000 were imprisoned, with many later executed or exiled. Thus ended the first fully formed proletarian state in modern history.

Louise Michel, leader of the Montmartre Women’s Vigilance Committee, wrote that “blood flowed in rivers in every arrondissement taken by Versailles. In each place, the soldiers stopped their carnage only when satiated, like wild beasts.” Artists living in Paris documented the bloodshed they witnessed. Paintings, drawings, and photos from the time tell a story of revolution, counterinsurgency, and mass destruction in just 72 days.

Unlike the bourgeois revolution of 1789, the Commune started as an uprising of workers who had lost faith in the National Assembly of landlords and capitalists. The Franco-Prussian War, fought over royal alliances and territory, had resulted in the Prussians routing the French army and laying siege to Paris. Food shortages and massive inflation resulted, exacerbating poor living conditions. When a new wave of protests chased Thiers and the bourgeoisie out of Paris, workers’ associations seized the means of production and resumed operations at factories shut down by their owners. From March to May 1871, the Commune swiftly deconstructed what remained of the Second French Empire by redistributing resources, separating church and state, promoting free and accessible education, lowering government wages, setting term limits, and severing police from political power.

A photograph by Ernest Charles Appert shows Communards standing in front of the downed Colonne Vendôme, a monument to the First French Empire under Napoleon. This highly symbolic gesture accompanied the burning of the guillotine, marking a departure from the 18th century’s indiscriminate violence. The Commune transferred economic and military power away from wealthy elites and made positions of authority revocable for politicians, soldiers, and police officers alike. The flight of private property owners reduced violence and petty crime in the city, as Karl Marx described in The Civil War in France.

Artists questioned what gave property owners the right to control and privatize art, laying out plans for decentralized practices divorced from bourgeois nationalism. In mid-April, a coalition of artists including Gustave Courbet and Eugène Pottier — the lyricist of the worker anthem “L’Internationale” — published a series of proposals for a new paradigm of public art. The Manifesto of the Paris Commune’s Federation of Artists called for entrusting artists with the management of their own interests, establishing communal methods of empowering them, and promoting the public’s right to culture, all maintained by a committee elected through universal suffrage.

Women of the Commune advocated against the heteropatriarchal imperial order, taking up arms alongside men and agitating for better labor conditions. Socialist illustrator B. Moloch depicted French women defending a barricade at Place Blanche during Bloody Week. It was the women workers of Paris who first seized the National Guard’s cannons in March and prevented them from firing. They sewed and stacked barricades and fought Versailles troops while nursing the wounded, leading to a new public image based on autonomy and leadership. A lithograph by W. Aléxis exemplifies this: A woman wields a red flag and casts a disdainful glance at hideous caricatures of Thiers and German Emperor Wilhelm I.

The rise of socialist feminism also provoked reactionary portrayals in some political cartoons. Images of the pétroleuse spread among anti-Commune propaganda, which accused peasant women of setting fire to major government buildings like the Hôtel de Ville and Tuileries Palace. These buildings were in fact more likely incinerated by male Commune soldiers, revealing how women’s empowerment inspired political misogyny. Some artists depicted the pétroleuses admiringly, while others were more lewd and debased. Many adapted their likeness to the mythical Marianne of the 1789 Revolution. This stereotype no doubt aided in the demonization and mass execution of Communard women.

Indecisiveness led to stagnation and infighting among the Blanquists and Proudhonists — who roughly represented socialist and anarchist tendencies in the Commune, as respective followers of Louis-Auguste Blanqui and Pierre-Joseph Proudhon — ultimately allowing the French bourgeoisie to recapture the city by force. German leader Otto von Bismarck agreed to assist the Versailles government, releasing more than 100,000 imprisoned French soldiers to aid in the counterrevolution. Together the German and French armies encircled Paris, laying siege to the Commune.

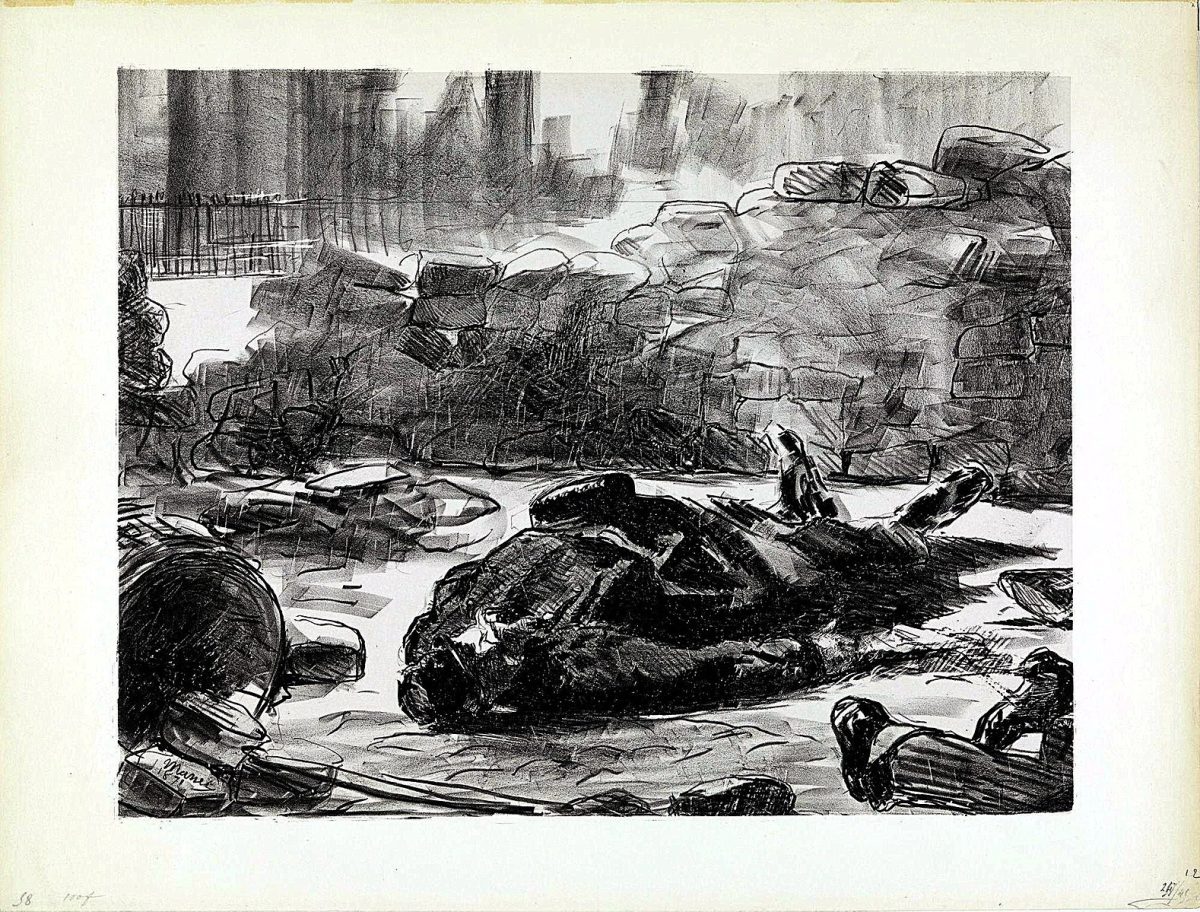

Anarchist artist Maximilien Luce painted massacred Communards in shades of deep blue. Édouard Manet, André Devambez, and Gustave Boulanger each created visceral battle scenes. Manet’s brother Gustave worked in the Ligue d’union républicaine des droits de Paris (the Republican League of the Rights of Paris), which attempted in vain to forge a peaceful resolution. Édouard, who also identified as a Republican, was not in Paris during March or April, but arrived in time to witness the Commune’s destruction and the corpses strewn about the city. Two of his lithographs from this time, The Barricade and Civil War, use sparse linework and shadowing to convey their gravity. While Manet was not a vocal supporter of the Commune, these drawings reveal his own conciliationism and sympathies with the victims.

Since its demise, the Commune has remained an influence to artists and revolutionaries worldwide. In 1883, Russian artist Ilya Repin painted a memorial near the Communards’ Wall, with a large crowd stretching out of frame. During the Cultural Revolution, the Chinese Communist Party proposed implementing a democratic electorate with open discussions in the style of the Commune. Vladimir Lenin drew comparisons between Napoleonic France and pre-revolution Russia in 1908. Lenin later danced in the snow after the Bolshevik Revolution surpassed 72 days — the length of the Commune’s existence.

The Paris Commune remains a hot topic of political debate, yet art criticism is sorely lacking. Left-wing media tends to channel its analysis into party/state politics, but as philosopher Alain Badiou articulates, its real lessons lie in its application to the ongoing revolutionary experience: “In the space of 40 years, young Republicans and armed workers brought about the downfall of two monarchies and an empire.” These artworks may not receive as much attention as the widely known Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements that followed, but the liberal pleasantries of the Third Republic would have never materialized without the radical putsch that introduced new ways of thinking.

0 Commentaires