This year marks the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune, known as essentially the first successful Communist revolution. For two months in 1871, the people took over the city, and photographs by Bruno Braquehais, currently in the collection of the Getty Research Institute, depict the drama — and destruction — of the period.

Braquehais is considered the father of French photojournalism for his images documenting the rise and fall of the Commune. Many images depict the wreckage that ensued at the end of the Commune’s reign. But unlike other photographers of the period, he also took pictures of people during the Commune as they posed optimistically in front of monuments and barricades. His photos suggest a sympathy with his subjects.

In 1871, France had just been defeated in the Franco-Prussian War and formed a new government, the Third Republic, comprised mostly of conservative monarchists. But in Paris, the National Guard was largely made up of members of the urban working class. After the war, the National Guard took control of 400 muzzle-loading cannons and placed them in working-class neighborhoods. Braquehais captured this tension in his image of cannons looming like sentinels over Montmartre, protecting its denizens from an impending threat. This seemingly minor act, documented almost incidentally by Braquehais, ended up being critical to the Commune’s success.

On March 18, 1871, soldiers of the Third Republic attempted to take away the cannons in Montmartre. A member of the National Guard was shot and killed. Word of the shooting spread, and a crowd rapidly formed. But when a general ordered his men to fire their bayonets into the crowd, they refused. Instead the soldiers broke ranks, switched sides, and joined the people in their protest.

As Paris turned on the Third Republic government, officials fled the city. In the vacuum of power, the National Guard seized strategic buildings. In Braquehais’s photo, Communards stand proudly by a cannon at the Rue de Castiglione, in a city they now controlled. By March 19, only one day later, they raised a red flag of victory over the Hôtel de Ville. The Commune was born.

Bruno Braquehais, Communards with a cannon at the Rue de Castiglione (1871), albumen print

Under the new model there was no single head of government — no president, no mayor, and no commander-in-chief. The Commune began enacting a series of progressive reforms. These included abolishing military conscription, separating church and state, regulating child labor, prohibiting employers from imposing fines on their workers, and providing free education.

Bruno Braquehais, The Vendôme Column, built by Napoleon, being pulled down by the Commune (1871), albumen print

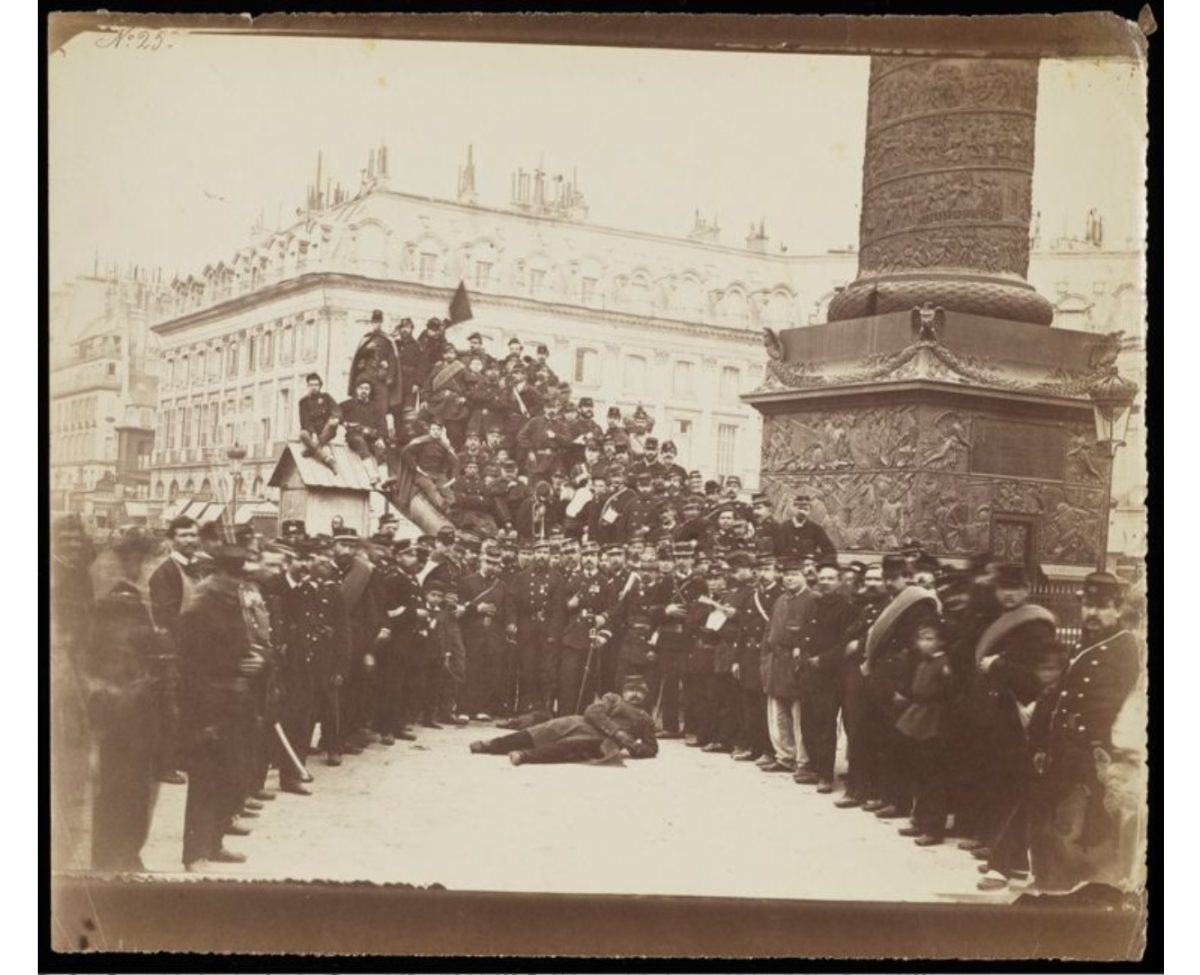

The Commune also resolved to tear down certain monuments. Their biggest target was the Vendôme Column, a 130-foot-tall pillar topped with a statue of Napoleon in Roman garb, and ringed with bronze plates made from the cannons of armies he had conquered. The Commune viewed it as a symbol of imperialism. On May 16, the column was pulled down to great fanfare. Once again, Braquehais was on hand to capture the event. The dust had barely cleared before spectators rushed in to grab souvenirs and take photos, including this large group portrait Braquehais took of Communards as they struck humorous poses in front of the former emperor’s monument to himself.

Bruno Braquehais, Group portrait of Communards at the Vendôme Column (1871), albumen print

But the exiled Third Republic government was plotting to take back Paris. Finally, on May 21, soldiers of the Third Republic marched into the city. The call for barricades went up, but the Communards were vastly outnumbered. Since previous revolutions, Paris’s old winding alleys had been replaced with wide boulevards, thanks to Haussmann’s renovations, so it was easier for the French army to attack. When they needed to get around a barricade, they simply plowed through buildings. Braquehais’s photograph of houses in the Rue de Ville that have been nearly cut in half give a sense of what everyday Parisians suffered.

In response, the National Guard set fire to major landmarks, including the palace of the Tuileries, the traditional residence of French monarchs. Braquehais framed this image of the palace’s destruction around a statue of the Roman war god Mars, seen in the background, as a commentary on the violence. Between the two sides, Paris was almost totally destroyed.

-

Bruno Braquehais, Interior of the Tuileries with a statue of the Roman god of war Mars (1871), albumen print -

Bruno Braquehais, Destroyed buildings at the Rue de Ville (1871), albumen print

One by one, neighborhoods fell to the Third Republic and prisoners were executed by firing squads. No one is sure of the exact number of people killed, but at the time it was estimated to be over 17,000. By the end of La semaine sanglante — “Bloody Week” — it was over. The author Gustave Flaubert wrote of the situation, “The sight of the ruins is nothing compared to the great Parisian insanity … One half of the population longs to hang the other half, which returns the compliment.”

Bruno Braquehais, Destruction at the Ministere de Finances (Ministry of Finance) (1871), albumen print

The Third Republic asserted its authority in Paris by rebuilding monuments the Commune had pulled down, including the Vendôme Column. In Montmartre, where the revolution had started, they built Le Sacré-Cœr, a massive basilica that is now a tourist attraction.

The tragedy of the Commune led many people in France and abroad to seek out photographic souvenirs of the events. But the French government monitored these images closely, censoring photos that might lead to disturbances of the public peace. Images of ruined buildings were acceptable, but portraits of people were scrutinized: they could only depict Communards in a negative, criminal light, and furthermore, they were often used to hunt down those who had participated. Braquehais published his images in an album, but unlike other photographers, he did not include any accompanying text to give judgement on the Commune — an absence that has been read as a subtle sign of his pro-Commune sympathies.

0 Commentaires