The first few pages of Aminder Dhaliwal’s Cyclopedia Exotica (Drawn & Quarterly, 2021) are easy to gloss over, but it pays to stick with it. Opening with passages on ancestry and origins, the graphic novel traces the lineage of an “exotic subspecies of archaic” creatures. Instead of a rare ungulate or bird, however, the book observes a mythical minority: the cyclops people.

We learn that cyclopes lineage includes asocial herders and cave dwellers; they possess one eye and flat noses; and their reproductive organs include three vaginas, a two-pronged penis, one breast, and three uteri. Then, on page six, a shift occurs. While introducing Etna, the first female cyclops to grace the cover of a “popular nude magazine” (renamed Playclops for that issue), the page’s design warps. Letters twist and tumble as Etna begins to speak to the reader, her speech bubble blocking out the encyclopedia’s text. “Blegh! What a dull way to read about a minority,” she jokes. As the fourth wall crumbles spectacularly, Etna peels back the page to the next chapter, and to the true beginning, of Dhaliwal’s latest offering.

When lulled into a sense of complacency, people often accept harmful stereotypes when only a fraction of a story is told. Cyclopedia Exotica challenges this by parodying the archaic compendium, delivering broader messages on the complexity of race, gender, and identity. We are introduced to a full cast of multidimensional characters. There are Tim and Pari, a mixed couple expecting twins. Another couple, both cyclops, attempt to bridge their individual dreams: Latea, a model, aspires to make a difference in her work, while the older Pol envisions settling down and starting a family. (They also adopt an adorable cyclops dog.)

Pol’s friend Bron grapples with a botched eye surgery that was supposed to transform him into a two-eyes (the politically correct term for two-eyed people). Bron hangs out with Arj, a queer, socially awkward cyclops who was bullied as a child. Twins Jian and Grae are a famous artist duo, navigating cyclopes issues through a series of relational performances, installations, and videos that slyly echo Marina Abramovic and Yoko Ono. Finally, there’s Vy, an activist who once modeled the lift and separator — a garment that forces the appearance of two breasts — and Etna, the original 1978 Playclops model, who acts as our guide. Through short vignettes, originally published on Dhaliwal’s Instagram as a weekly comic, beginning in 2019, we are offered brief glimpses into the multifaceted cyclops world.

One way that Dhaliwal interfaces with this universe is through creation and representation. Within marginalized communities, older cultural paradigms are often both revered and considered regressive. (For example, the 1990 film Paris Is Burning increased visibility for the trans community, but was criticized for its “obsession with an idealized fetishized vision of femininity that is white” by theorist bell hooks.)

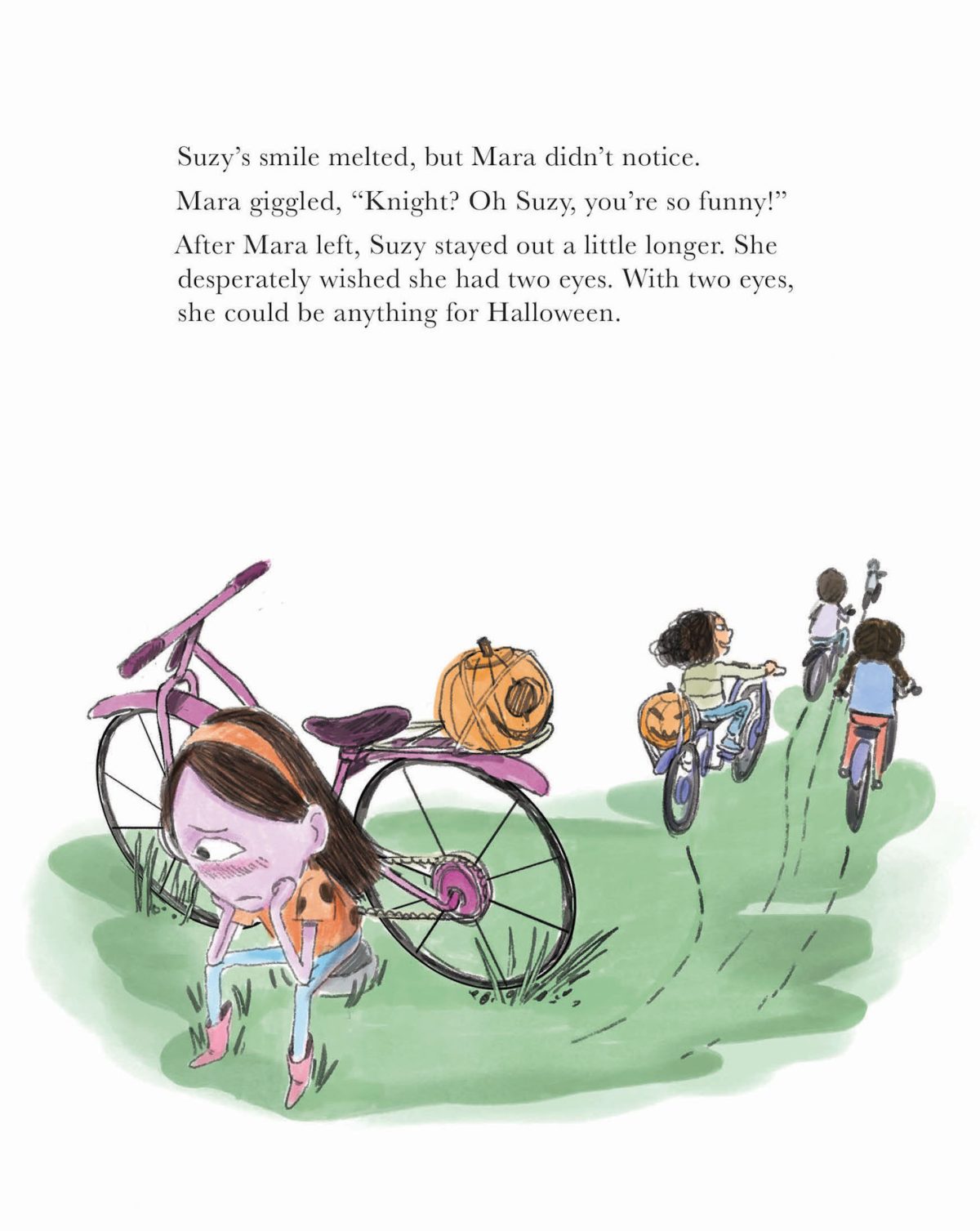

In Cyclopedia Exotica, two works of art are referenced: Suzy’s One Eye, a children’s book that debunks the myth that cyclops are monsters, and a 1978 sci-fi film, Cyborg. Rather than take an academic approach to these works, Dhaliwal shows us how their mainstream popularity affects her characters. Vy introduces a special film screening of Cyborg by criticizing the film’s problematic premise, in which robot cyclopes take over the earth and destroy two-eyes culture. (The punchline here is that this problematic film is screened four times in a film series themed on cyclops representation because there are no other cyclops-centered films.)

We see a one-page ad promoting Suzy’s One Eye, which reveals a portrait of the two-eyes author, Leonard Cartemis. The ad contains oddly aggressive language: “No one else can capture the voice of a young cyclops girl in a Two-Eyed space! No one can write the story of a young Cyclops girl and her friends better than Cartemis!” As a result of this insensitivity to actual cyclopes writers (perhaps a nod to publishing’s #ownvoices movement), Bron resolves to write his own book, but, trapped in his own anxiety, inadvertently references Suzy’s One Eye.

While these two scenes are written with humor, reality weighs heavily: there simply isn’t enough representation for cyclopes, so existing public-facing culture is held to impossible standards. Etna relates her experience with the controversial Playclops cover, noting reactions that mirror the hypocritical stances of some progressive liberation movements — in particular, ones in which feminism and agency intersect with body image. “I desperately wished for sweeping changes in cyclopes treatment when I was younger. But change is slow and stubborn,” she explains of the past. “When the cover was published, I was considered the first sex symbol for a group of people who were ‘unsexy.’ And then I was responsible for their over-sexualization when the submissive cyclops trope emerged.”

But not all characters fixate on representation. When trying on a cyclops-designed dress for a gallery opening, Pari doesn’t like what she sees. “I hate the dress but I want to support the existence of the dress,” she says, obliquely referencing what writer Kat Chow calls “rep sweats.” Dhaliwal offers a no-nonsense solution to this crisis: Pari puts on her trusted black dress and then goes about her evening. She progresses on her own terms.

Similarly, Jian and Grae make cyclops-driven artworks that are unapologetic, even if patently facetious: in one comic, Grae explains how a painting contains four different shades of white as a commentary on the nuances of cyclopes issues, before Jian interjects awkwardly: “I thought you said to order four cans of pure white?” In the duo’s exhibition, Eye Sore, Bron and his friend Hes have to sign waivers before they enter the exhibition space; once they are in, the doors close and a timer starts, Saw-style. They spot a doorway obstructed by a floating, translucent eye installation, which they pop with conveniently placed spears in the corner of the room.

At the end, a video of Jian and Grae tells them that they were played all along: Eye Sore is about violence against cyclopes in the entertainment industry. Dhaliwal traces this storyline back to a past comic, in which Grae flies to Hollywood to find work, but discovers that the only narratives being greenlit are those that perpetuate dangerous stereotypes. Perhaps drawing on her own observations as a female animator of color working for companies such as Disney and Nickolodeon, Dhaliwal encourages us to think about tokenism and fetishization in relation to visibility.

These conversations and their linked traumas rumble uneasily under the surface. Ads address dangerous surgeries that aim to “correct” cyclopes features, such as adding an extra eye or erecting a false nose, offered through the fictional big pharma company Unifeye. Latea, who uncomfortably accepts modeling gigs from Unifeye, reads that cyclopes have a higher mortality rate in childbirth due to a lack of shared research between institutions. Shorter, one-page images also show two-eyes protesting mixed couples, such as Pari and Tim, and a cyclops fetish search on “Pornhut” looks disturbingly similar to hits for videos of trans people and Asian women, two communities subject to extreme violence and hypersexualization.

However, Dhaliwal is not interested in singular narratives of violence, especially since a prevailing stereotype about cyclopes is that they are monsters. Instead, she navigates the hardship with humor, focusing mostly on the interior lives of her characters. Cyclopes and eye puns are plentiful — “blindspots!” “I have no depth perception!” “there’s only one ‘i’ in charity!” — and moments of embarrassment or doubt are shared openly. There is a community, Dhaliwal reminds us, even if the characters feel alone sometimes.

This poignant reminder unfolds slowly in Bron’s story. Throughout, we see him plagued by nightmares about his eye surgery as he voluntarily removes himself from both the cyclops and the two-eyed community. Toward the end of the book, he meets Hes, who lost one of his eyes in an accident. Hes encourages Bron to reread Suzy’s Eye, implying that there may be more to learn from the book. As we read the story with Bron — gorgeously rendered in color by Nikolas Ilic — it becomes clear that the message is about finding confidence from within, despite external conditions.

Cyclopedia Exotica is Dhaliwal’s second book, but it follows much in the same vein as her first, Woman World (2018): in both, she builds an environment that is hostile and limiting, whether through racial aggression or patriarchy. Through her contemporary characters, however, she challenges fixed boundaries and narratives. In Cyclopedia Exotica’s epilogue, we are reintroduced to the compendium format. Each character’s full background, motivation, and inspiration is explained (Dhaliwal referenced famous cyclopes in history; for example, Pol is based on Polyphemus, the man-eating cyclops from Homer’s Odyssey), but this time, we have already seen how they live. In this sense, Dhaliwal frees them from the static confines of myth and, perhaps, even their own beliefs about who they are supposed to be.

“Sometimes, there’s a story we tell ourselves,” Etna says in the book’s final pages. “And sometimes, a story is told about us. Some parts of our story define us. But the nuance and humanity is lost in the encyclopaedias.”

Cyclopedia Exotica by Aminder Dhaliwal (2021) is published by Drawn & Quarterly and is available online and in bookstores.

0 Commentaires