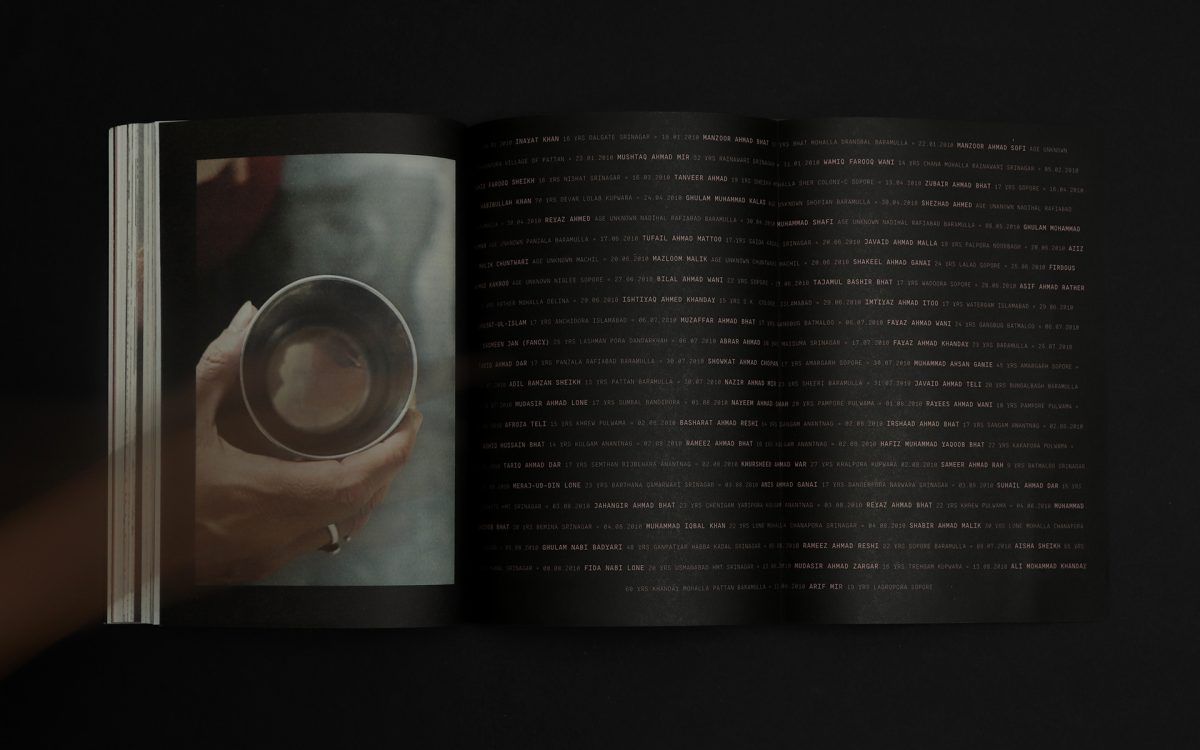

In the summer of 2010, a 17-year-old boy named Tufail Ahmad Mattoo was killed in Srinagar by government forces as he returned home from school. Across Indian-controlled Kashmir hundreds of thousands of people erupted in protests demanding independence from Indian rule. By the end of that year, over 118 civilians had been killed by the state in these protests, many of them young people in their late teens and 20s, some of them children as young as eight years of age.

Alana Hunt, an artist and writer from Australia, had left Kashmir the day Mattoo died. She had spent three years in New Delhi by then, and would often visit Kashmir while studying at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Back home in Sydney, Hunt watched as the death toll in Kashmir rose day by day. She communicated online with friends in the region, who were caught under suffocating curfews. Cups of Nun Chai, her decade long body of work, emerged from this juncture which she describes as being “as personal as it is political, as geographically and culturally dislocated as it is grounded.”

“Meanwhile” she writes in the book, “Australia barely took note; there was a gaping silence on Kashmir in its 24-hour news cycle, and other lives simply went on. Indifferent. Unaware. Elsewhere.”

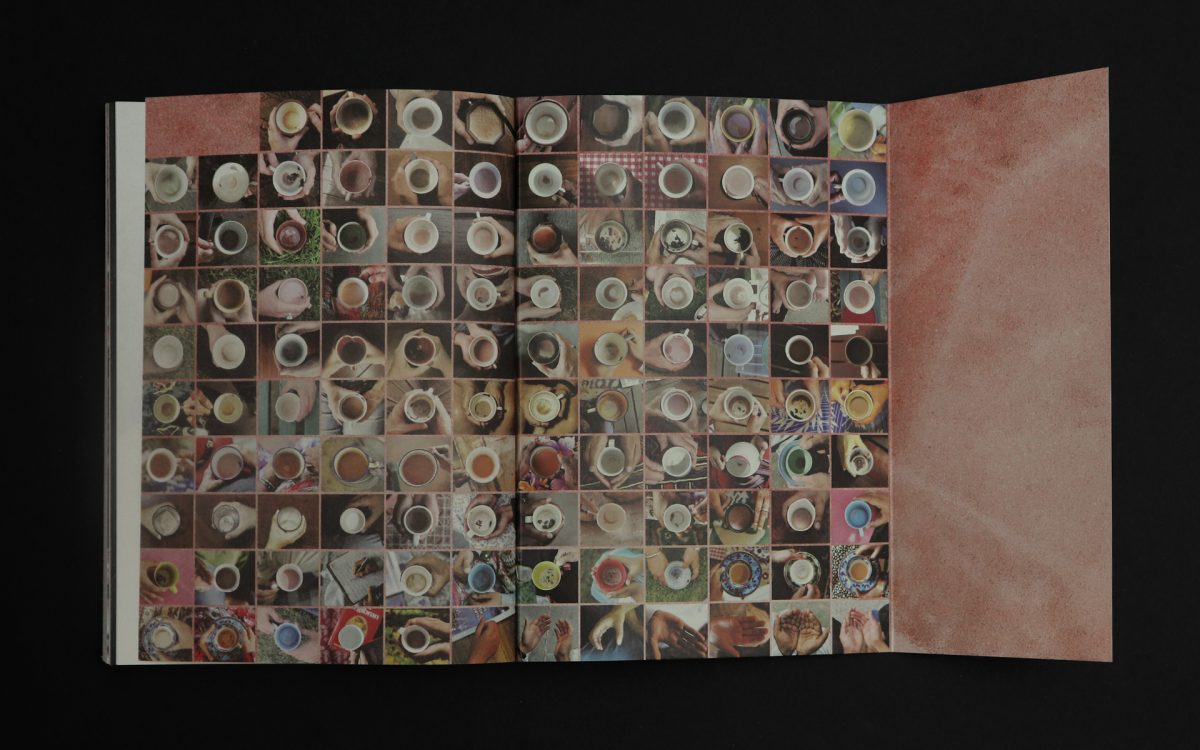

Nun chai, a distinct salt tea ubiquitous in Kashmir, became the catalyst for a requiem to this loss of life unfolding through 118 conversations with 118 people in Australia, India, and Kashmir. Each conversation forged one part of an accumulating constellation that connected Kashmir to other experiences of state violence, nation-making, and colonization globally. With each cup of tea photographed, and each conversation recorded from memory, the work first accumulated on a website, then circulated in the newspaper Kashmir Reader, and has most recently been published as a book by the New Delhi-based press, Yaarbal Books.

In the text’s introduction, Hunt writes that the project began as a “gesture towards the people of Kashmir who feel and know this loss the most, and as an attempt to render tangible what so many outside Kashmir do not know.”

“The work moves against the normalization of violence, in an attempt to mark this loss, and to grasp at what surrounds it,” she explains. “It is an archive of small moments, remembered within the terrain shaped by the persistent violence of colonization and nation making.”

Through deeply personal encounters the book reflects on how decades of structural state violence disrupt and affect everyday life in Kashmir. These informal conversations, over a deceptively simple act of sharing tea, convey the larger political resistances and aspirations of people in the contested region of Kashmir. However, an acute sense of grief hangs heavy over each conversation through which the work’s core as a memorial is maintained.

There are no direct images of violence in the book, nor of the heavenly landscape Kashmir is known for. This is in stark contrast to stereotypical representations of the region in mainstream Indian media, Bollywood, and the international press. Hunt’s emphasis on everyday experiences, shared over a cup of tea, highlights things that are often missed amidst the dominant mainstream media narratives of beauty and violence that Kashmir has generally come to be identified with in the Western world.

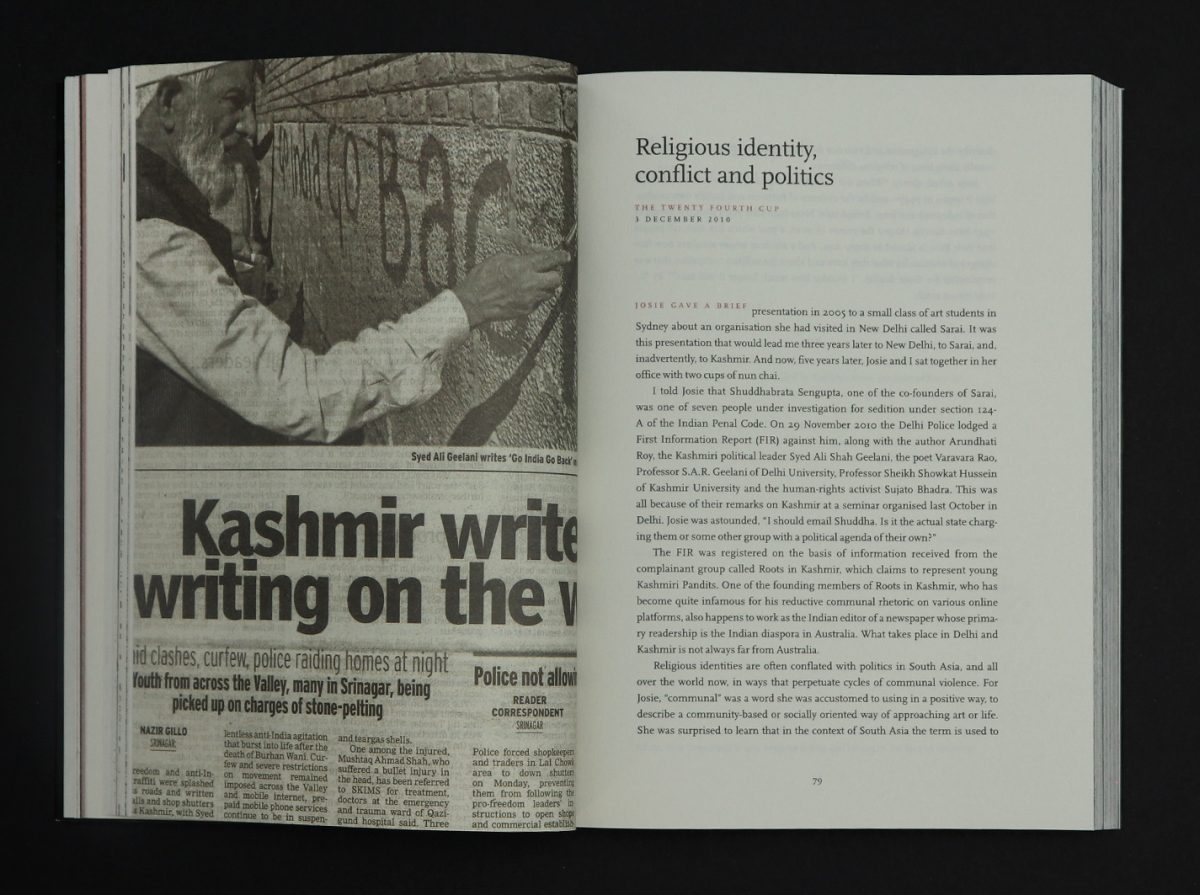

Making reference to the work’s serialization in Kashmir Reader, a daily newspaper published from Srinagar, the book also incorporates newspaper clippings. Significantly, in the midst of the project, Kashmir Reader was banned for three months from October 2016, due to its bold, independent reportage of the conflict. Here, newspaper clippings provide not only a distinctly Kashmiri visual and textual counterpoint to Hunt’s own work, but also subtly point to the political dynamics at play in the lead up to and following the newspaper ban.

It is worth noting that Cups of Nun Chai was published in the aftermath of August 5, 2019 – the day when Kashmir’s autonomous status was unilaterally revoked by India’s Hindu nationalist BJP government, which also divided and downgraded the former state into two federally governed union territories. The unprecedented military crackdown and near total communications shutdown that followed cut people off from each other and the outside world for about six months. Recently, the Indian state has accelerated the process of settler-colonization in Kashmir that many fear is aimed at engineering a demographic change in the only Muslim-majority state in India.

In this context, Cups of Nun Chai attempts to forge an international dialogue that converses with the aspirations of ordinary people in Kashmir, whose humanity is preserved — and shines — through this book, despite decades of suppression and silencing by the Indian state. Through an intimate gesture of listening over a shared cup of tea, the book offers a response to the absurdity of state violence, countering its normalization in Kashmir with an artistic act of memorialization that runs against the attempted erasure of people’s memories by the state.

Cups of Nun Chai, by Alana Hunt, is now available from Yarbaal Books.

0 Commentaires