Two different memories came to mind while I was looking at the brightly colored abstract paintings and beguiling works on paper in the exhibition Caetano de Almeida, at Van Doren Waxter (March 25–May 15, 2021), which, according to the gallery, is de Almeida’s first New York exhibition in almost five years. The first memory was of a podcast hosted by Charlotte Burns in 2017. Her guest was the artist, critic, and curator Robert Storr. In discussing his feelings about the terms globalism, cosmopolitanism, and internationalism, Storr stated:

Modernisms started in different places at different times but many of them started in Brazil and the United States, roughly at the same time around 1913.

The other memory was of a conversation I had with the painter Leda Catunda, while I was researching her work for a two-person museum show in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Both Catunda and de Almeida are Brazilian artists of the same generation (born in 1961 and 1964, respectively), living in São Paulo, which is the site of the second-oldest art biennial after the Venice Biennale.

This meant that Catunda was directly exposed to a wide range of international artists when she was starting out, but she was aware that the rest of the art world routinely ignored an older generation of Brazilian artists, such as Lygia Clark (1920-1988) and Lygia Pape (1927-2004).

While Storr was right to emphasize the simultaneous rise of Modernism in Brazil and the United States, and how quickly it became a worldwide phenomenon, I think he neglected to mention a crucial fact — the central role a city, and its culture and institutions, can play in these matters. Postwar artists in Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and New York took different paths. And while some of them were regarded as international art stars, others were seen in a narrower light.

Maybe it is time we stop thinking about peripheral aspects of the art world, such as the marketplace and auction records, and start looking at what is in front of us. In de Almeida’s case, there is a lot to look at and think about, even for viewers who are unaware of the ways he has made use of Brazil’s history of abstract art and its long engagement with geometric abstraction.

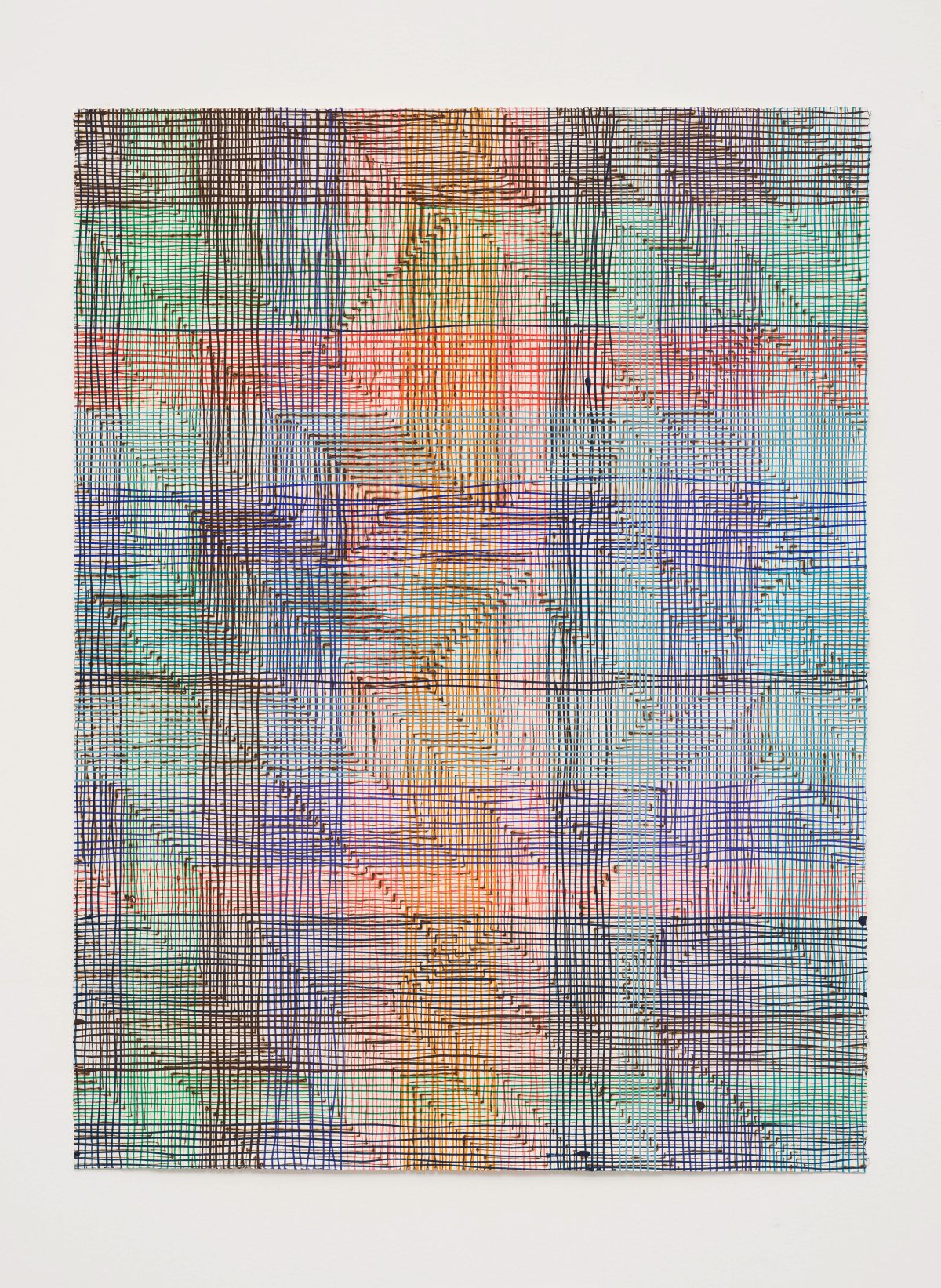

The show includes six paintings and seven works on paper, all dated 2020. The paintings can be divided into two related groups: one in which the canvas is carefully gridded off in pencil; the other dominated by circular forms and fragments made of evenly spaced bands. In these painting one sees traces of the pencil lines mapping out the orientation of the bands. The drawings are all composed of lines made either in acrylic ink or with a heated device that leaves a burn mark in the paper. If these drawings are any indication of his practice, it seems that they form a distinct body of work within his oeuvre.

By placing the burnt lines next to those in acrylic ink, with very little space between them, de Almeida achieves a dense weave. While the lines are different colors, the burn marks are all brown. He uses each medium to form a different pattern, and yet one does not seem superimposed over the other.

In every drawing, I found myself moving closer and closer to the work; at first it seemed like de Almeida was drawing on a transparent surface, but when I came close I saw he was not. For reasons that I cannot explain, it was as if the combination of ink and burn marks made the paper almost disappear. The other perceptual eye grabber was the layered density conveyed by the combination of lines, while the concentration and repetitiveness of handmade lines reminded me of a cluster of filaments and wires in various kinds of machines.

De Almeida is an urban abstract artist. There are references to nature, but it seems to me that his overarching subject, at least in the paintings he starts with a pencilled grid, is the organized chaos of urban living. It is one thing to see a city from an airplane as you pass over it on your descent and another to walk its streets. This discrepancy struck me while looking at de Almeida’s brightly colored, seemingly improvisational abstractions.

The square painting “Up close, from afar” — I only learned the title after I thought about the discrepancy between aerial and pedestrian views — might cause a vertiginous feeling in the viewer. De Almeida packs together lots of small, bright sections in this work, more than in the two related paintings. As with the drawings, there is no ideal spot to look at it; this is underscored by the thickness of the paint, which varies just enough to notice, and because de Almeida paints on the canvas carefully stretched over the sides. The shift between the painting’s right and left side and the surface expands our experience of the work and turns the artwork into a physical object, a thing.

In some clearly defined areas, the pencil grid on the gessoed canvas is painted with a thin wash of color. Right next to these areas is a coat of paint thick enough to become tactile, however smooth the section. The placement, size, and color of the hard-edged shapes, some of which take up a noticeably larger area than the shapes around them or overlap different-colored sections, follow an elusive logic. I get the sense that de Almeida lets colors call to colors, and shapes to shapes, and that he works his way across the painting without an overall view of it. That he does not work within a signature structure is one of his many strong points.

At the same time we should remember that Brazil is the home of Brasília, a planned city that was developed in 1956 by Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, and Joaquim Cardozo. This link between a utopian community and a modern city suggests a relationship to geometry distinct from the formal, ostensibly neutral model developed by American artists. Once I had this thought, I began wondering how much of de Almeida’s work I was seeing and how much I was translating.

Anyone who knows about mid-20th-century Brazilian poetry will know that Carlos Drummond de Andrade (1902-1987) is a major figure. If you cannot read Portuguese, then you have to read translations of his work. It has often been said that what gets lost in the translation of a poem is the poem. I don’t agree. Something comes across, even as something gets lot.

Many people used to believe that art could achieve something universal, but we know that is not true. The universe is a big place. By focusing instead on what we now call the global, we downplay the local and what nuances it might possess. However, this does not mean nothing comes through. De Almeida might not show in New York regularly, but a lot is going on in his work and it more than holds its own against the geometric abstraction celebrated here.

Caetano de Almeida continues at Van Doren Waxter (23 east 73rd Street, Manhattan) through May 15.

0 Commentaires