Nineteen forty-seven marked a rupture amid ongoing waves of movement and displacement in South Asia’s modern history. The year saw independence from British rule, which also delivered two Partitions, communal riots, the creation of borders, and the formation of new and disrupted constituencies.

The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 begins here, uncovering an era of hopefulness and tragedy in four South Asian countries — India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka — which collectively make up almost a quarter of the world’s population. The exhibition, on view at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York through July 2, spotlights a range of South Asian and foreign architects working in the region to construct the identities of these new and troubled nation-states.

The show is organized not by nation but by project theme, demonstrating the vastness of the post-Independence architectural program. The ambitious display spans the construction of modernist capitals, large-scale housing plans, industrial sites and factory towns, and government buildings, as well as new universities, cultural centers, and places of leisure. Connecting these works are their distinctive style, use of local materials, and reliance on a surplus of labor.

Detailed architectural models, blueprints, images of construction sites, and a mix of contemporary and archival photographs showcase key works of the era. Some of the more widely known projects include Raj Rewal’s Pragati Maidan, literally translated as “progress grounds,” a concrete spatial structure, assembled primarily through manual labor, that housed the Hall of Nations for the 1972 International Trade Fair in New Delhi. The designs of Muzharul Islam, a preeminent architect of East Pakistan and later Bangladesh, convey a focus on educational spaces, including the Dhaka University Library, the Institute of Fine Arts, and Chittagong University. Geoffrey Bawa’s projects in Ceylon and later Sri Lanka highlight the use of concrete frames and open courtyards in the new industrial architecture of the island nation.

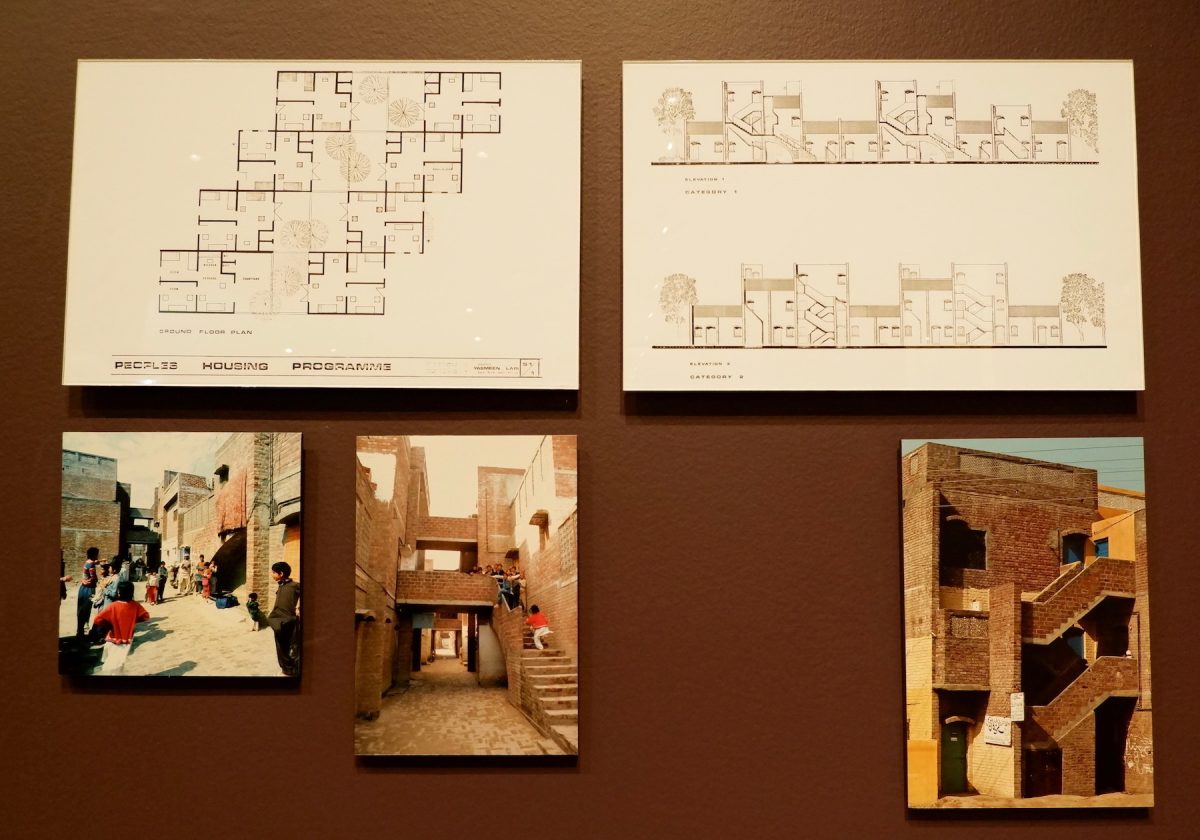

The exhibition also makes a point of foregrounding the work of two women architects — Yasmeen Lari of Pakistan and Minette de Silva of Sri Lanka — who have yet to receive their due. It’s no surprise that the architectural field in South Asia was male-dominated, but select women, often with access to elite education, managed to enter the discipline. De Silva and Lari were among the few women in the region to receive major commissions in their own names.

Lari, known as Pakistan’s first woman architect, oversaw the nation’s first public housing scheme, a 787-unit Anguri Bagh housing project in Lahore. In 1980, she designed a participatory plan to resettle 13,000 families from Karachi’s slums to formal housing, allowing for incremental relocation and prioritizing pedestrian streets and public shared spaces. But her projects’ difficulties later on illustrated the immense challenge that architects and policymakers faced when attempting to address housing shortages through planning. Relatively modest projects could not resettle nations — public investment was lacking, and state-subsidized housing was often distributed based on employment and failed to serve the lowest classes, especially those in informal sectors. Anguri Bagh never moved past its first phase, and it did not meet its objective of constructing 6,000 units to house the city’s urban poor.

The show probes these limits of modernist construction, asking: Can an architectural form that originated in the West ever be truly decolonial? Though the exhibition aims to focus on builders from South Asia, it cannot ignore the dominating presence of Western architects with Euro-American names outnumbering Bangladeshis, for example. The curators seem prepared to preempt this critique throughout the show by arguing that South Asian modernism was in fact deeply South Asian, rooted in the realities of labor and local production.

As curator Martino Stierli writes, “The notion that Chandigarh (and subsequent modernist projects in South Asia) represents a simple transfer of Western knowledge to a new setting seems glaringly reductive.” In the show’s opening display, Yash Chaudhary documents how Le Corbusier’s massive concrete complex — a new modernist city in the hills of partitioned Punjab — dwarfs its plentiful, dark-skinned workforce clothed in saris and lungis.

Even so, Stierli and co-curator Anoma Pieris point to the power of modern architecture to serve as “an instrument of cultural emancipation,” not only from British colonization but also from the insistence that modernism is at its core tied to the West. But while the exhibition is concerned with the contradictions between the European and the South Asian, the universal and the specific, a deeper contradiction lies in the reliance of this “cultural emancipation” on a more acute form of subjugation — a low-paid, often caste-oppressed labor force employed to construct temples to modernism and liberation. The specter of cheap labor, and the monuments it enabled, is present throughout.

The ability to construct such buildings, especially with a lack of prefabricated materials, rested on the remnants of an extractive colonial relationship. Unsurprisingly, the economy of construction entrenched internal hierarchies in the newly independent states. The exhibition notes this clearly, and with Stierli citing the “material culture of manual labor” as one of the main South Asian attributes of modernist architecture in the subcontinent. Stierli quotes Adrian Forty, writing that Indian construction was defined by “concrete, abundant unskilled labour, [and a] lack of productive capital.”

In other places, the exhibition seems to evade the realities of political violence on the ground. The show repeatedly references the horrors of Partition, but its main invocation in design is through a few small public housing projects that failed to meet exponentially outsized housing demand. Louis Kahn’s Bangladesh Parliament Building is on prominent display, but the bloody war and genocide committed by the Pakistani military, which led to the need for the new national building, goes unacknowledged. The Sri Lankan Civil War, which erupted toward the end of the exhibition’s timeframe and lasted 26 years, is barely given a sentence. These omissions are expected somewhat given the massive scope of history and population covered, but they do cast doubt on the centrality of modern architecture in crafting the nation.

Despite its contradictions and complexities, the modernist period presents a bygone moment in which national governments of South Asia invested in a progressive vision of the public. In today’s India, Narendra Modi, as part of a larger campaign against Nehru’s secularism, has repeatedly attacked the emblems of the modernist movement. In April 2017, Rewal’s Hall of Nations was suddenly torn down overnight, and the upcoming remodeling of India’s central government headquarters is yet another display of ultra-nationalism.

The new plans signal a distinct turn away from the international. The elegant hallmarks of South Asian modernism — lattices of exposed concrete and interior courtyards venerating light — have no place in India’s new architectural vision. They are to be replaced with heavy domes, lightless interiors, and a central avenue apt for the grandest of military parades.

The Project of Independence: Architectures of Decolonization in South Asia, 1947-1985 continues at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Midtown, Manhattan) through July 2. The exhibition was curated by Martino Stierli, MoMA’s Philip Johnson Chief Curator of Architecture and Design; Anoma Pieris, guest curator and professor, University of Melbourne; and Sean Anderson, former associate curator, Department of Architecture and Design, MoMA; with Evangelos Kotsioris, assistant curator, Department of Architecture and Design, MoMA.

0 Commentaires