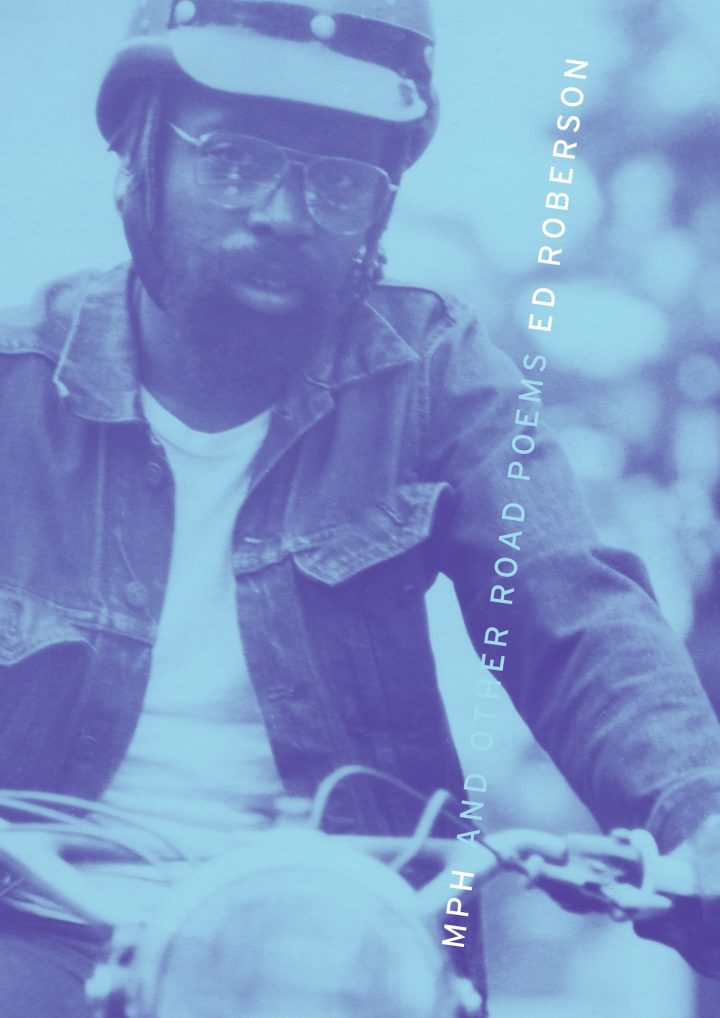

Over his half-century career, Ed Roberson’s poetry has been all across the globe, exploring all manner of mythological lore and historical experience, but for the last couple of decades he has mined a rich vein of what one might call “urban ecopoetry.” His most recent collections, To See the Earth Before the End of the World (2010) and Asked What Has Changed (2021), are firmly rooted in the cityscape of Chicago, but overarchingly, achingly, preoccupied by the changes the natural world is undergoing under the stress of the Anthropocene. It’s with a kind of wry, elegiac nostalgia, then, that one contemplates the spectacle of a much younger Roberson heading out west on that icon of internal combustion, a BMW motorcycle, in the rediscovered early work of MPH and Other Road Poems (Verge Books, 2021).

1970, when Roberson rode from Pittsburgh to San Francisco and back with two friends, was a heady time for motorcyclists: the 1969 film Easy Rider was merely the bleak climax of a countercultural love affair with the motorcycle that had been alight since at least the mid-1950s, when Marlon Brando and James Dean had romanticized the the biker. And the cross-country travel of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957) was just a recent instance of what seemed an inherent American urge to “light out for the territory.” But if “going west” evokes prairie schooners and Manifest Destiny, for an African American poet it also evokes that archetypal westward journey, the Middle Passage:

the killer was it wasn’t any fairy tale’s enchanted white horse they got on for beauty and couldn’t get off. it was white it was the sails of the prairie clouds and schooners and space with no overboard other than the slavers wrote the vessel in on we washed up free

“where is that slick black man / on that slick black // motorcycle going”? In the collection’s later poems, Roberson sorts through the tangle of motives behind his journey and the implications of his travels. As he makes clear at the very outset, the poet goes west on the back of a motorcycle neither under duress nor with the hopefulness of the pioneers, but in

response to the sense of wandering of rootlessness of isolation in your own country of a despair the mortality of freedom of the adventure the new as territory of quest of myth a campaign.

The motorcycle ride from Pittsburgh to the Pacific is a quest-romance, an exploration of American culture and American mythology, a seeking-out of one’s place in a variety of new and storied places: “my place is in place / where i am.” Of course, for a poet as sharp-eyed and observant as Roberson, it’s “also a question / a getting down dirty to looking.” The poems of MPH are spangled with observation, both flatly rendered and strikingly metaphorized: a tractor-trailer, “meso- / american in / its mask’s iconography”; “road signs barely readable for bullet holes”; a sunrise, “the rose cloud tiers stripes blood steps of aureole aztec pyramids.”

The journey west is not all landscape, but involves as well a variety of human interactions, both on and off the road. When a child in a school bus flashes a tentative “V” at the riders, Roberson’s companion “throws both hands off the handlebars open / armed returns a two-hand peace sign with no hands / / on the bike.” Some of these interactions have an undertone of menace: “A kid rolls the window / the rest the way down / and spits at us.” Near Sioux Falls,

a buffalo head horned helmet -ed motorcycle gang will ride up beside you close enough to take over the direction of your handlebars and ask you where you think you going— we cool we said west

An old woman sits in front of an adobe house, “a single pot in her lap” — “a lovely fragility narrow / it is at the bottom / widening gracefully it is / at the center” — “almost as if she were / hiding the fact she wanted to sell it.”

Roberson strikingly captures the physical sensation of motorcycle riding, the sense in which the biker’s guiding of his machine resembles a grappling with palpable material:

like did you ever ride motorcycle

the strength of a curve come thru the steering

to get straightened out under

the grind agreement the guiding of your hips

is

could tell you

what you wanted to know

the polishing of rough stone

into harder light

your own strength

The cyclist wrestles his mechanism as Jacob wrestled the angel: “cross country / you neither of you let go / until you’re blest with / the pacific.”

The Pacific is the ultimate horizon for the westbound American traveler, so much of whose experience, Roberson notes, is taken up with “wall to wall horizon.” The horizon, the boundary of our vision of the earth, is a symbol of the future, the unknown:

We can’t see over the curve,

so horizons

front for the whole beyond,

lessening limit

with their non-existence

as literal

point for point beauty

for what isn’t seen.

A “front” for the unknown, but also gesturing toward the utopian, the imaginative reconciliation of the heavens and the earth, the whole biosphere:

arrival’s terms for paradise

come round, horizon’s expectations

for climax

to its mirage—

wrapt around the sphere:

all those Heavens

fronting for the plain unfound.

The story of MPH itself involves something of a journey. The manuscript of poems Roberson wrote in response to his 1970 motorcycle odyssey (and a follow-up trip to Mexico the next year) got lost in the shuffle of work for his second book, Etai-Eken (1975). Yet he still had some of his notes, and lines and phrases from the work kept finding their way into his writing. In 2015, preparing to move from New Jersey, he came upon a substantial chunk of the manuscript in his attic. Those pages, and other rediscovered early motorcycle poems, form the core of MPH and Other Road Poems, augmented by a variety of Roberson’s writings over the intervening decades that speak to his experiences of biking west.

In perhaps the most poignant of these later pieces, the 75-year-old poet, recovering from brain surgery and traveling to California by train, watches the road “when a black motorcyclist / swept screaming speed up a curve”:

Patty said There’s Ed… ours is not the only time. we are not the only travelers. and this is not even the only road. But someone needs to see themselves coming back to in the future. someone needs collected and carried across the room the country the food the offering of going on.

The “principle of motorcycles,” Roberson remarks, is to “keep moving / to stay up.” As a poet, he has certainly kept moving since his first trip west: the early poems of MPH are fresh and vibrant, and while the more retrospective later works complicate and subtilize those immediate records, his language has only grown more vigorous over the years. Despite its disparate origins, MPH and Other Road Poems does not feel at all like a miscellany, but rather impresses one as a unified, keen-eyed, and high-octane cultural and spiritual road trip: an “offering of going on.”

MPH and Other Road Poems by Ed Roberson (2021) is published by Verge Books and is available online and in bookstores.

0 Commentaires