The term “lace” today might summon images of over-the-top wedding dresses, intricate lingerie, or perhaps the doilies and table runners that adorned our grandmother’s table: sweet, decorative, and maybe a little kitsch. But when the latticed fabric first appeared in the 16th century, says Kaat Debo, director of the ModeMuseum (MoMU) in Antwerp, “it was something completely new.”

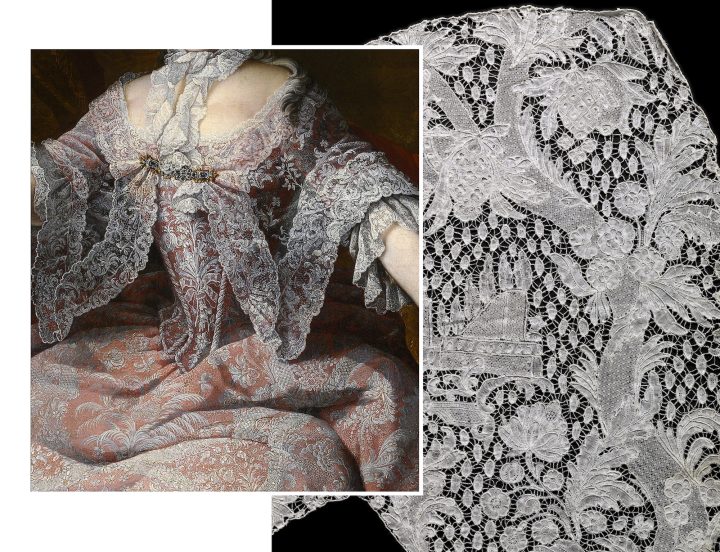

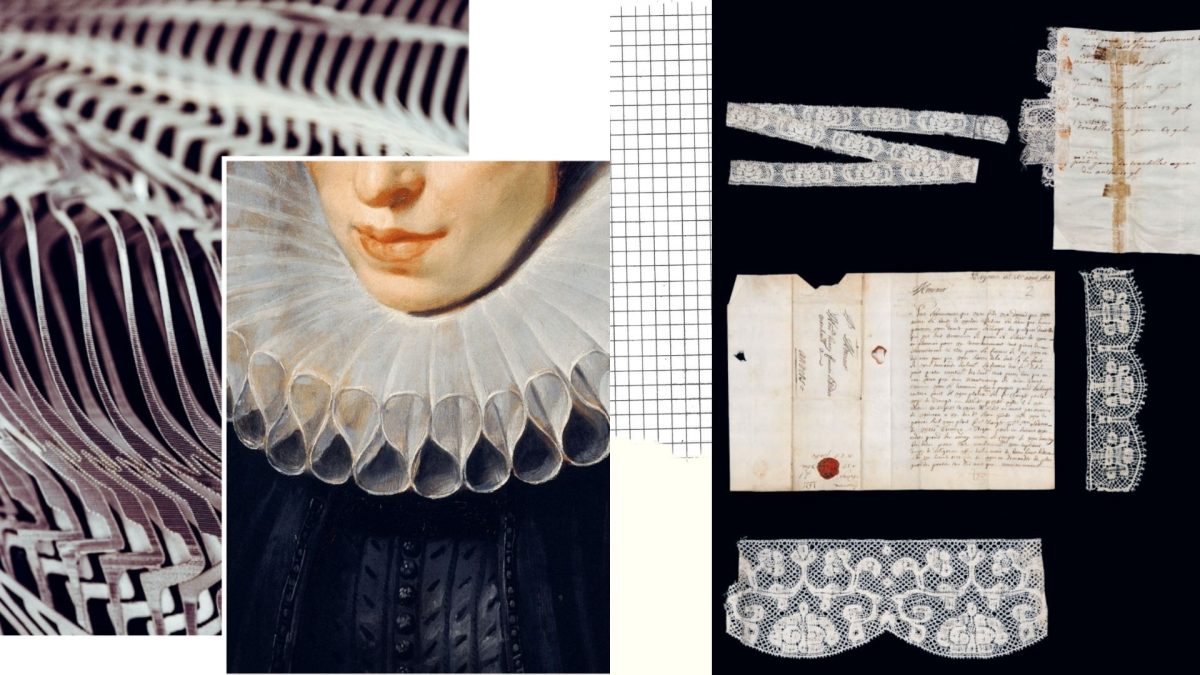

“Lace, originally intended as an openedge finishing for clothing and interior textiles, creates a dimension that both obscures and accentuates the boundary between textiles, body and space,” Debo writes in a foreword for the book accompanying the recently opened exhibition P.LACE.S – Looking through Antwerp Lace. The show explores the city’s role in the trade and production of lace across the centuries, bringing together historical fabrics, paintings, and archival documents to reveal how the delicate, weblike design became a staple of art, craft, fashion, status, and commerce.

P.LACE.S is on view at the museum and at four sites connected to the history of lace in Antwerp. Presentations at the Plantin-Moretus Museum, which holds one of the oldest archives in the world on the lace trade, and the St. Charles Borromeo Church, home to a large collection of 17th- and 18th-century lace, illuminate the international lace trade and its local production, respectively. At the Snijders & Rockox House, where Nicolaas Rockox, mayor of Antwerp, displayed his art collection, the exhibition focuses on lace as a symbol of wealth and class.

The final location is the Maagdenhuis (Maidens’ House), a former orphanage for girls turned into an art and historical museum. Throughout history, lace has been primarily produced by women, and in the 16th century, the

Maagdenhuis housed a workshop where they learned sewing and lacemaking. For the show, a film by Rei Nadal inspired by the aesthetic of Dutch 17th-century paintings follows three young girls who lived at the orphanage and made lace.

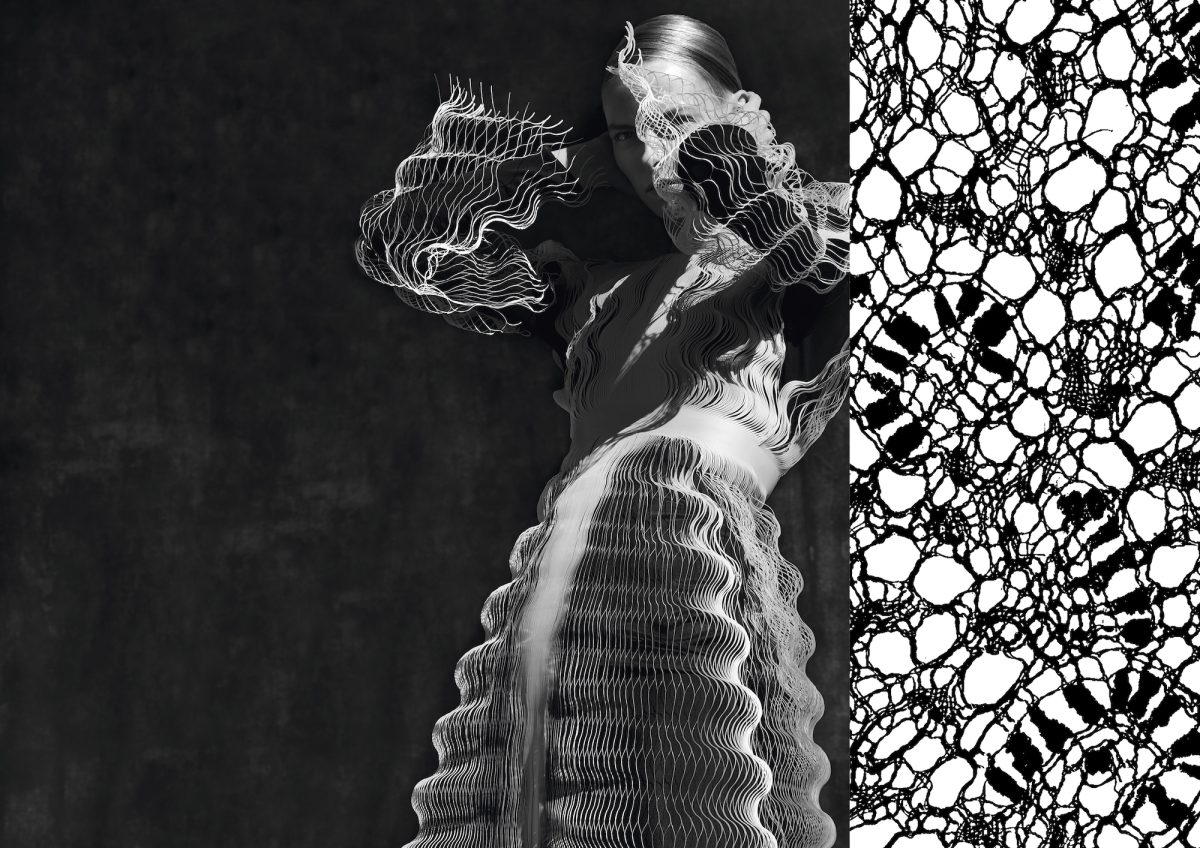

MoMu’s own galleries, meanwhile, center on the impact of lace on fashion from its origins to the present. Most interestingly, the presentation highlights industry innovations, like 3D printing and laser cutting, that are changing how lace is produced and worn — designers including

Iris van Herpen, Azzedine Alaïa, and Prada are all using new technologies and mediums to reimagine the possibilities of the persistent webbed fabric.

“This ambitious project tells the extraordinary story of the emergence of lace as a new luxury product at the beginning of the sixteenth century, and of the prominent role played by the city of Antwerp: a story of extraordinary professional skill and craftsmanship, technology and innovation, international trade and enterprise,” writes

Debo. “It is also a story of girls and women who played an important role not only in the creative process and the production of lace, but also in the commercial activities of the international lace trade.”

0 Commentaires