LOS ANGELES — Call me old-fashioned, but at the preview of the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures — slated to finally open on September 30 after years of funding-, construction-, and pandemic-related delays — I wanted to see what it was actually like to watch a movie at the museum dedicated to the art form. In the midst of a pandemic and in a time where over a century’s worth of movie history is accessible from one’s own home, it can sometimes feel like both audiences and studios alike have begun to devalue the theater experience.

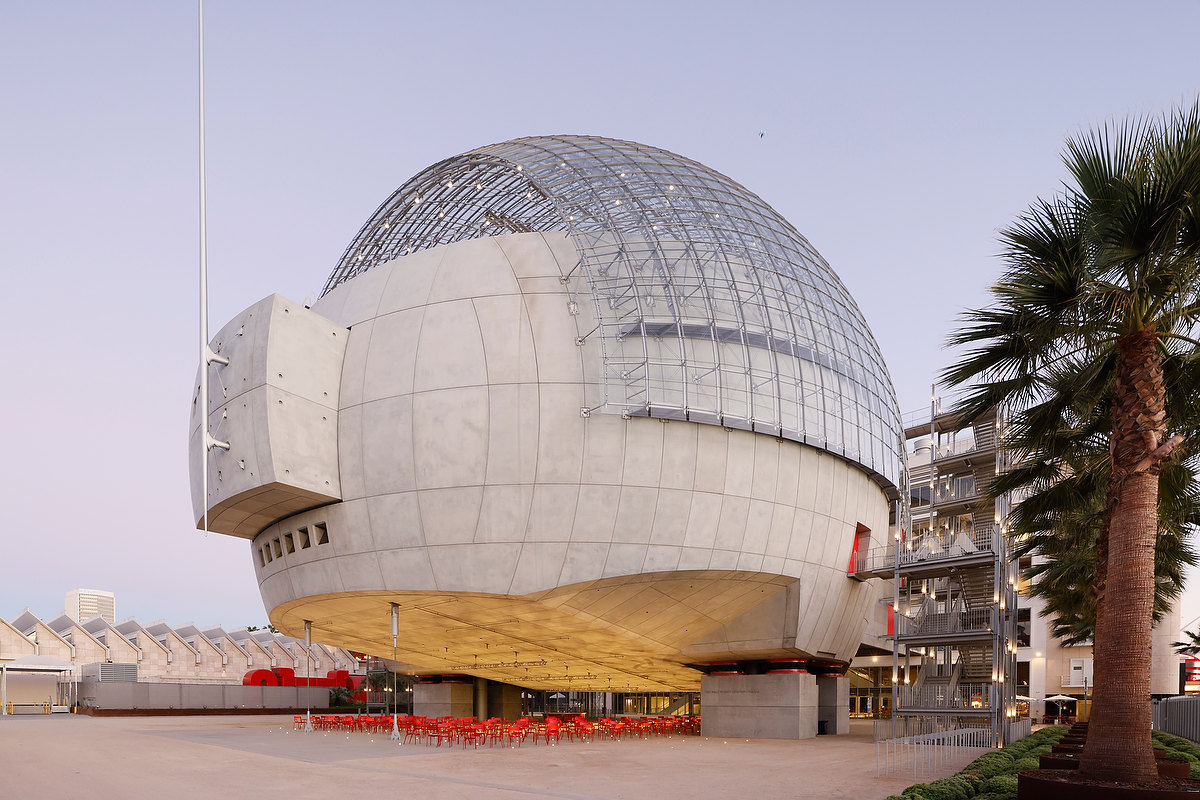

The 1,000-seat David Geffen Theatre sits inside the architectural centerpiece of the Academy Museum, a 45,000-square-foot concrete and glass sphere that rises above Fairfax Avenue and has been referred to by locals as the “Death Star,” though architect Renzo Piano, in his opening remarks at the preview ceremony, would prefer you compare it to a “soap bubble” or a “dirigible.” The theater itself is luxe, filled with plush, red seats arranged arena-style. One would think it would be the ideal space for the Academy to host the Oscars if it had the capacity. But on the day of the preview, it was just me and no more than a dozen other people catching the afternoon matinee.

It wasn’t Lawrence of Arabia, but senior director of film programming Bernardo Rondeau had programmed the documentary short “A Place to Stand,” a curiosity meant to show off the 70mm projection and immersive sound of the Geffen Theater as well as the depth of film history that will be on view at the Academy Museum. The 17-minute film was commissioned by the government of Ontario for Expo 67 to showcase daily life in the province and earned its place in film history with its innovative use of multi-dynamic image technique.

Of course I did eventually make my way into the main exhibition halls of the museum in the adjacent May Company building, a 1939 Streamline Moderne former department store rechristened the Saban Building and adapted into 50,000 feet of exhibition space by the LA-based design firm WHY. The core exhibition Stories of Cinema covers three floors, and attempts to tell a comprehensive, if convoluted, story of the history and creative process of movies. “That’s ‘Stories,’ plural,” explains Jacqueline Stewart, chief artistic and programming officer of the Academy Museum. “Our premise is that there are multiple histories of film, some of them only now coming to light and multiple ways of looking at them.”

Stories of Cinema is intended to be a dynamic exhibition which will evolve over time, with the intent that different figures and films will be featured down the line. Though its subjects may change, one can see its narrative structure in place. Its first main gallery, simply titled “Significant Movies and Moviemakers,” showcases six films and artists in vignette-like installations, not unlike the opening credits of a film. For the museum’s inauguration, legends like the Greatest Film of All Time (Citizen Kane) and Bruce Lee will greet visitors first, before they move on to invisible artists like cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, as well as the canon-busting legacies of Oscar Micheaux and Real Women Have Curves. These six legacies don’t make an appearance again in any significant way for the rest of Stories of Cinema, but the way they are contrasted with each other sets the tone for the delicate balance the museum tries to strike.

When I last visited the museum at the beginning of 2020, the exhibition halls of the Saban Building lay bare, yet to be filled by the “revisionist” history promised by the Academy. From afar, Stories of Cinema holistically details the process of moviemaking, from its inception in storytelling and writing, all the way to its marketing and promotion. But interwoven into these exhibits are ugly truths and necessary corrections to Hollywood legend.

In a glamorous gallery that displays several Oscars, an empty case stands in place for a statuette that Hattie McDaniel never received for her performance in Gone With the Wind — as was customary for supporting roles at the time — with a placard mentioning that she was forced to sit at a segregated table at the awards ceremony. In one room dedicated to the massive, painted backdrop of Mount Rushmore used in North by Northwest, one section acknowledges that the iconic monument defaces land sacred to the Lakota. Most strikingly, in a space that details costuming and makeup, an installation displays makeup once used to turn white actors into racist caricatures for the screen. On the jars of foundation are labels with blunt descriptors like “Chinese” and “Black (Minstrel).”

In the end, though, the movie business is show business. The glitziest, brightest, and most eye-popping hall in Stories of Cinema is dedicated to the Academy Awards ceremony, playing clips of acceptance speeches and displaying glamorous outfits worn at the Oscars. Carpet throughout the floors of the Saban Building is the same red as the one walked on by the stars at the awards ceremony. The top floor of the exhibition halls is bound to be the museum’s biggest blockbuster: Hayao Miyazaki. The museum’s inaugural temporary exhibition not only features over 400 pieces of art relating to the movies of the Japanese animation master, but also “immersive” moments where fans can lie on a grassy knoll under an animated blue sky or bask under the canopy of the Mother Tree from Princess Mononoke.

To cap it all off, though, is the most vulgar attraction of them all in The Oscar Experience. For an additional $15 on top of the price of admission, visitors will get to record a simulated video of themselves triumphantly accepting an Oscar onstage at the ceremony. There was already a long line for it throughout that afternoon.

While exploring Stories of Cinema, “A Place to Stand” strangely resonated with me as I wandered through the exhibits detailing the largely unseen work that goes into the making of a movie. In “A Place to Stand,” clips of labor and industry are shown alongside idyllic beauty and scenes of Ontarians enjoying the pleasures of life. A man honing a new ice skate immediately cuts to a Toronto Maple Leafs hockey game. In Stories of Cinema, a massive flatbed editing console shares the same room as the Rosebud sled from Citizen Kane, while mere steps away from Dorothy’s ruby slippers sits a camera dolly, an apparatus that requires multiple operators just to capture the perfect shot.

I couldn’t help but think about how the approaching opening of the Academy Museum — a space that will celebrate the work of these below-the-line craftspeople — is set against the backdrop of Hollywood’s labor strife with the union that represents these same artisans. One day after the Academy Museum is set to open on September 30, the International Association of Theatrical Stage Employees, fighting for better pay and working conditions, will begin a strike authorization vote that could shut down Hollywood’s production to a grinding halt.

The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures (6067 Wilshire Boulevard, Mid-Wilshire, Los Angeles) opens to the public on Thursday, September 30.

0 Commentaires