The difficulty of these times is that before bringing in new ideas, we’d have to destroy all the simulacra that the century and its favorite instrument, television, have generated to replace everything that has disappeared. This is why I’m passionate about the new information grid, the internet, blogs, etc. Inevitably, there’s some slag, but a new culture will be born of it.

– Chris Marker, April 2008

Ok be honest who was doing the whip crackin emote at the MLK fortnite event

Twitter user @koptfn, August 2021

At the dawn of the internet age, science fiction writers and futurists predicted the coming of “the metaverse.” Its time has not yet quite come, as evidenced by my browser not recognizing the term as a properly spelled word, but tech companies are trying to make it happen now more than ever. The metaverse is where, through immersive technology like VR and complex persisting online spaces, the real and digital worlds meld. In books, films, comics, and more, some fantasists conceived of wondrous, infinite realms of adventure and imagination. Others darkly speculated on how businesses would exploit and dominate these creations. Somewhere in between these two poles is the sheer oddness of touring a recreation of the National Mall in Washington, DC during Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech within an online multiplayer shooter game.

In August, developer and publisher Epic Games announced that it had partnered with TIME to present a special “interactive experience” in its flagship game Fortnite, as part of the news company’s ongoing educational initiative “The March,” about the 1963 March on Washington. When a player engages the “March Through Time” event, they find themselves and several dozen fellow users in “D.C. 63,” a fantasy version of the Mall. This map features real-world landmarks — the Lincoln Memorial, Washington Monument, and the reflecting pool — as well as areas where they can test themselves with small challenge games and museum spaces with exhibits on segregation, the Civil Rights Movement, and more. Looming over all is a giant four-screen video installation of Dr. King delivering “I Have a Dream,” the sound of which is clearly audible no matter where you are on the map. Once the speech is finished, players are rewarded with a special item (you can earn it more quickly if you complete all of the aforementioned challenge games).

If you don’t play video games, you might only be familiar with Fortnite as something kids love to use to fight with and yell at each other online. But I’ve heard it better described as “a party that’s a platform.” It’s true that, by far, the most popular element of the game is its “Battle Royale” mode (in which 100 players enter and kill each other until only one remains), but in the time since its initial launch in 2017, the game has continually evolved its social dimension. There’s no shooting in D.C. 63, and this isn’t the first such event Fortnite has hosted. Epic is investing heavily in crafting “entertainment experiences,” utilizing the basic tools and formats of the main gaming modes to allow for other forms of interaction and storytelling. So far this has manifested most famously as the various concerts that have taken place within the game, to great success (especially under the COVID-19 quarantine).

But is Fortnite really a good venue for an educational look at the fraught story of racial oppression in the US?

Maybe not.

Probably not.

Definitely not.

Epic did not fully think through the optics of letting characters in silly outfits (some of them trademarked figures like DC Comics superheroes) prancing throughout an event that’s presented to be as solemn and respectful as possible. It took around a week for them to limit the use of emotes (poses, dances, and the like) within D.C. 63. By that time plenty of players had already gotten their kicks and/or social media clout by messing around (you can see such behavior in the screenshots I took for this article, captured during a playthrough that happened prior to the fix). Even then, at the time of writing they have not yet managed to disable all emotes, including a whip-cracking motion, the single most offensive gesture one can make in this context. In spirit, this is not too terribly different from the class troublemaker kid who won’t stop joking during a field trip, but in this sphere such behavior is exponentially more ostentatious and disruptive to the intended effect (particularly if one is goofing off while looking like Master Chief or Rick Sanchez). But no amount of tinkering with possible player behavior can make up for the fundamental wrongheadedness behind this endeavor.

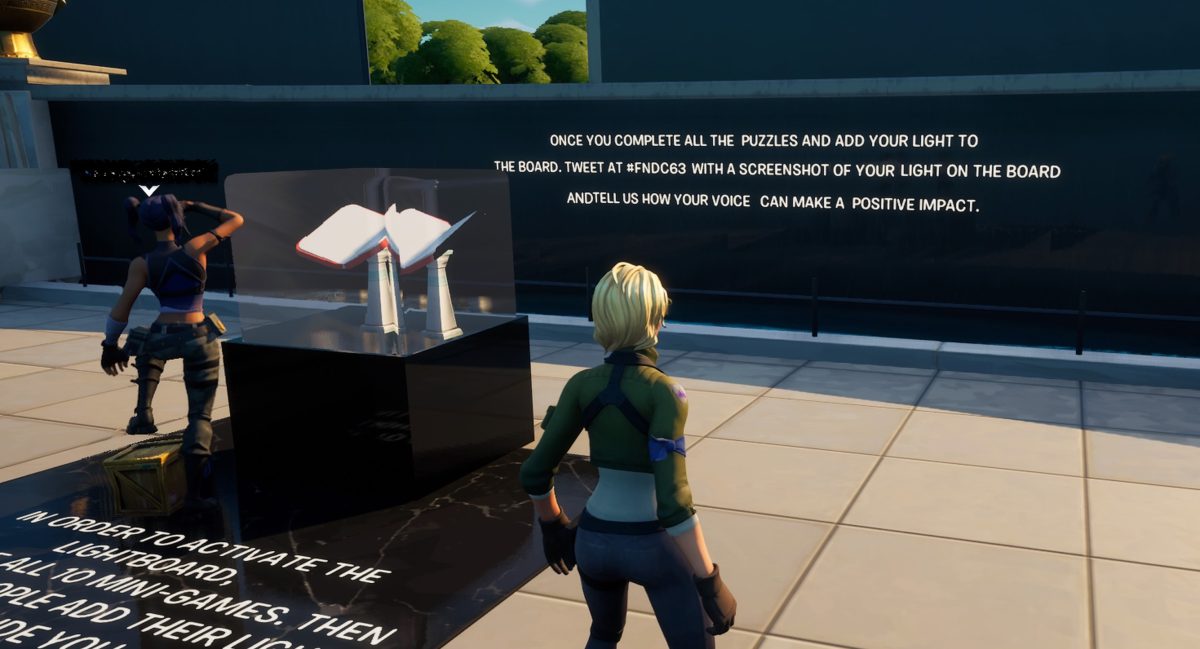

Despite all the good intentions behind “March Through Time,” it is a bizarre and cringe-inducing experience with inescapable “How do you do, fellow kids?” vibes. One great thing about video games is that they can seamlessly merge symbolic actions with actual actions. Fortnite encouraging you to “add your light” to a nebulously defined idea of positive change by creating magical glowing sigils throughout the D.C. 63 map is … not that. Crucially, despite the exhibits about subjects like the Freedom Riders, diner sit-ins, and school desegregation, the overall message obscures problems of racism in US history. The idea of “reaching the mountaintop” is rendered by having two players cooperate to light torches on top of an actual miniature mountain. This isn’t teaching anyone cross-racial harmony and solidarity; it’s basic preschool “get along” stuff. A virtual world in which one can inhabit whatever kind of body you so choose (this character customization process involves outward appearances literally called “skins”) is a poor platform with which to discuss problems of discrimination. Fortnite is not yet a metaverse, but a separate verse. Its exhibits are not of its own world, but a foreign one.

In the late 2000s, multimedia artist Chris Marker built Ourvoir, an island museum of digital oddities, his own work, and cinema history within Second Life, the first large-scale attempt at a constructed, inhabitable alternate world of the kind imagined by sci-fi writers. For Marker, the internet offered intriguing new possibilities for ideas he had explored throughout his long career. In a rare interview, conducted within Second Life, he praised it as “A dream state. The sense of porousness between the real and the virtual.” Referring to himself as “a cobbler,” he called Ourvoir an act of “supercobbling.”

But artists aren’t the only ones who “cobble.” Epic Games has built much of its popularity on imitating or outright stealing ideas from other sources and then integrating them into Fortnite. This has been present from its inception; the game was originally themed around “tower defense” (players cooperating to build structures and then fight off hordes of enemies). This is where the name came from — you build a fort to survive the night. Then Epic rapidly developed a battle royale mode which looked suspiciously like the format of PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds. More recently, the game introduced a “spot-the-impostor” mode that greatly resembles the indie mobile game Among Us. Among Us makes money with advertising, while PUBG is sold as individual copies. Fortnite, meanwhile, is free to play (its immense profits come from the ethically dubious practice of microtransactions). Epic can hence undercut competitors by offering similar kinds of play at a lower price and/or with a smoother experience.

This creativity-swiping gets even less savory when it comes to Fortnite taking dances devised and made popular by individuals and incorporating them as emotes. For a while within D.C. 63, one could disrupt a tribute to Black political action with a dance appropriated without compensation from a Black creator. If this is the shape of the metaverse, then it suggests a future virtual realm dominated by corporations leeching ideas, history, and our common heritage, collapsing all of them into culturally gentrified uniformity.

During my time in D.C. 63, I saw some players congregating before the giant screen of MLK — not playing around, not exploring the map, simply listening to him. Browsing the official hashtag for the event on social media turns up many apparently sincere attestations to its power. So, perhaps for at least a few users, the event is working as intended. But its envisioning of the past is not in line with MLK’s true spirit, but the mainstream media’s decades-long project to erase every trace of radicalism from his message. “Every memory can create its own legend,” says the narrator of Marker’s Sans Soleil (1982). “March Through Time” is how Fortnite twists the MLK legend to work within an aesthetic and engagement mode that simply does not fit the man, his values, or his movement. It embodies both the darkest possibilities of Marker’s conception of the internet “dream state” and the most sinisterly anodyne conception of MLK’s “dream.”

(@lavendermarii)

(@lavendermarii)

0 Commentaires