For artist Betye Saar, dolls are much more than objects of play. They are vessels for the imagination and the catalysts for storytelling. They create magical memories for children and conjure enduring memories in adults. They’re surrogate friends and confidants that soothe weary hearts. As totems, dolls are also capacitors of energy that summon good spirits or ward off evil. In her assemblage practice Saar harnesses this energy contained in found objects, combining them with symbols and imagery that speak collectively to themes of class, inequality, racism, and spirituality.

In her latest exhibition, Black Doll Blues at Roberts Projects, Saar turns to the familiar yet under-appreciated medium of watercolor. The show features a series of seven watercolor portraits of dolls from the artist’s personal collection. The title of the show belies the work’s celebration of the comforting, enduring magic of play, but it also reveals America’s lingering discomfort with racist objects and their origins. Evidence of this is found among the justifications people use to explain their enduring presence. Racist memorabilia is collected and inherited by some as nostalgic keepsakes, while others use these objects as tools to teach our complicated, violent history. Despite the range of rationales used by collectors to justify their existence, racist Jim Crow iconography has maintained a stronghold over our perceptions of Blackness, which continue to influence identity to this day.

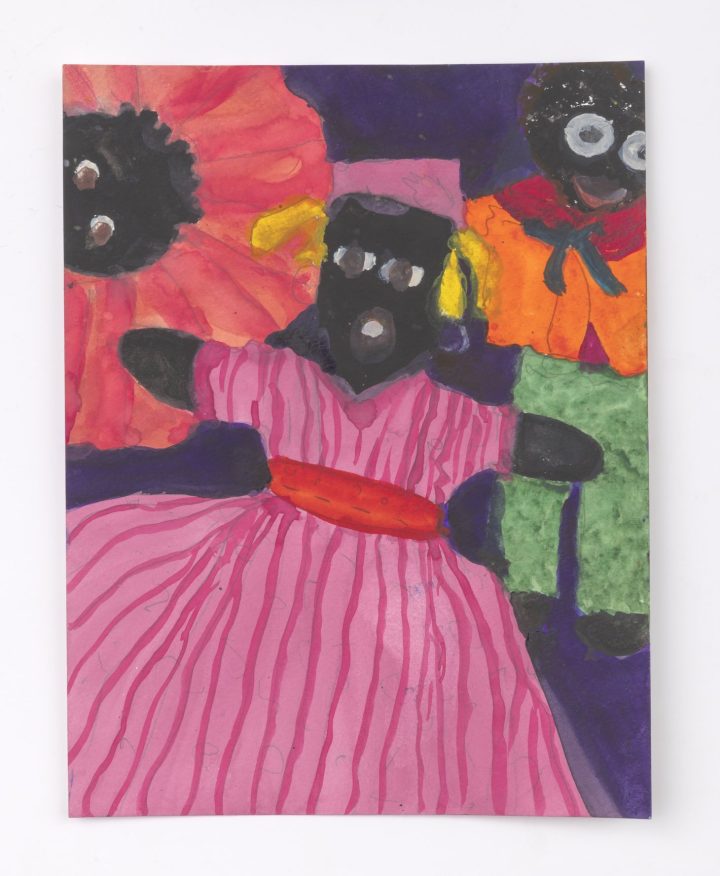

The 95-year-old artist began collecting dolls as an adult and has amassed a carefully curated collection of 40 to 50, which includes wooden dolls, rag dolls, mammy pincushions, golliwogs, minstrel dolls, and Haitian Vodou dolls. In 2020 Saar turned her artistic eye toward these subjects, departing from her signature medium of assemblage and opting for a creative detour into this series of irreverent paintings that celebrate the catharsis she found in play. The dolls are portrayed against brightly colored backgrounds of teal, purple, and red; they are painted in pairs or trios and attired in floral dresses, large colorful bonnets, and ribbon ties. Among the paintings, a few dolls make repeated appearances in new groupings while outfitted in subtly altered ensembles. The paintings capture phases of play that reminded me of the elaborate Barbie set ups I created as a child.

Saar remains a luminary among Los Angeles assemblage artists, an impressive cohort that includes John Outerbridge, Noah Purifoy, Senga Nengudi, and Judson Powell, all of whom applied conceptual themes to their medium. For many LA artists in the Black Arts Movement, assemblage drew from and combined Southern vernacular traditions of quilting, weaving, and doll-making with found materials. When Saar first showed “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” at Berkeley’s Rainbow Sign community center in 1972 she transformed racist Jim Crow iconography in response to the string of violent killings that became tragic markers in the Civil Rights movement. Her juxtaposition of these two eras, one marked by state-sanctioned caste systems and the other transformed by a radical referendum of those same segregationist Jim Crow laws, was encapsulated in “Liberation”’s own transformation of a “mammy” figure into fist-wielding, gun-toting warrior for justice.

The timing of that particular artwork converges with an important footnote in the history of commercial Black doll making in Los Angeles. Shindana Toys was created by Louis Smith and Robert Hall in the aftermath of the Watts Rebellion in 1968 to create toys specifically marketed to Black children. Shindana’s goal was to provide nurturing, uplifting, and empowering images to Black children through dolls that look just like them. These objects of play countered the erasure and the negative imagery found in contemptible collectibles and became important affirmations of confidence and strength that coincided with the Black Is Beautiful and Black Power movements.

While Saar does not have Shindana dolls in her collection, the proliferation of commercial Black dolls in the 1960s became the impetus for her to begin collecting Black dolls. While the appearance of caricatures in this series may be puzzling, it also suggests Saar’s personal reckoning with the origins of her dolls and their own symbolic liberation. Saar understands the politically charged nature of her art, and she is rarely shy about speaking her mind through it. It’s also important for viewers to reflect on their own relationship to racist iconography, and how this delicate, complicated relationship evolves over time.

I recently connected with Saar via email about her new paintings, which she created in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. It appears as though the process of painting this series has brought her some semblance of peace amid the chaos. Through assemblage she reconciled her relationship with the past. Through these watercolors, which are situated in the present, she has harnessed the energy of the objects that she lived with, recontextualized, and transformed throughout her career. For Saar, these dolls are not burdened by the past. However viewers must find their own path toward reconciliation in grappling with their personal relationship to this imagery. For me, understanding this distinction sheds light on the title of the show, Black Doll Blues.

***

Colony Little: Can you describe an early memory of dolls as you were growing up? Did you play with Black dolls as a child?

Betye Saar: I grew up in Pasadena, California, and as a child I never had a Black doll. I had dolls, sure, but they were never Black because they weren’t manufactured back then, in the ’20s and ’30s. I remember the first mass-produced doll was in the 1940s, but by that time I was a college student at UCLA and was too old to play with dolls.

CL: When did you begin collecting dolls?

BS: In the 1960s I was married with three girls and living in Laurel Canyon. One day I was shopping on Sunset Boulevard, the Sunset Strip area, and I walked by an antique store and saw this Black doll in the window. She was really expensive at the time so I didn’t buy her. But then I kept thinking about her, and maybe she was thinking about me? So I decided to go back to get her. So she was the first Black doll I ever bought.

CL: Do you source your dolls in the same manner as the objects you collect for your work? Can you describe the energy contained in the dolls you collect?

BS: I’m primarily an assemblage artist and get a lot of inspiration from finding used materials that have an intangible energy, a previous life. I shop at swap meets and estate sales and antique stores and always seek out odd and interesting things. I hunt and I gather. But then sometimes I shop with a specific purpose, like, for when I was creating “Woke Up This Morning, and the Blues Was in My Bed” (2019) I needed lots and lots of cobalt-blue bottles.

So, as I shopped for assemblage materials, I would also buy Black dolls if I came upon one I found interesting. A lot of friends send me dolls that they find from all over the world, from Amsterdam to Africa. Years ago, my brother Junie worked for LA City and once found a bag of Black dolls someone was throwing away. A friend who runs estate sales emailed me with a heads up that they were selling some. Of course, I went and found some new additions to my collection. People know that I collect Black dolls and that has helped me build my collection.

CL: Why did you choose watercolor, and what turned your attention toward your doll collection as a subject?

BS: This past year with COVID and the quarantine has been so strange. People trying to safeguard their health, [and] businesses, museums, and galleries closing. I wasn’t really interested in making my usual assemblages. One day I was organizing my little studio and decided to start painting with watercolors. Throughout my life I’ve used watercolor paints. As a young girl my mother always gave me art supplies, which often made me mad when my sister would get a bike or something. But all her focus on art supplies made me comfortable with watercolors, and art, of course. I also use watercolors for my sketchbooks when I travel.

So during quarantine I started off painting some of the images I often use in my artwork: suns, moons, hands. Then I thought “What else can I paint?” and I looked around my house and saw the dolls in the cabinet. I’d gather a group of them and lay them out on my art table. Sometimes I’d paint just girls, or just boys, or sometimes just one doll. I’d adjust their hats and smooth their skirts. Tuck their arms around each other. I enjoyed using really saturated colors, the red jackets, blue dresses, yellow hats. Watercolor was a familiar medium and the dolls a comforting subject.

CL: Some of your most notable works focus on reframing or recontextualizing Black caricature or racist commercial iconography. Is there an element of recontextualization for the Black dolls themselves in this work?

BS: Some might think that these dolls are derogatory stereotypes of Black people, and yes, I agree, some of them are. But I feel that mostly these dolls were created to be a comfort. And I painted them, not to reclaim Black identity or empower them, like I did back with Aunt Jemima. I painted them because I wanted to and it made me feel good. Painting the dolls gave me a project to keep me busy and keep me creating — which, in hindsight, is perhaps what I really needed to deal with all the scary things happening with COVID outside my house. Essentially, I’m 95 and I’m playing with dolls and having fun making art.

Betye Saar: Black Doll Blues continues at Roberts Projects (5801 Washington Boulevard, Culver City, California) through November 6.

0 Commentaires