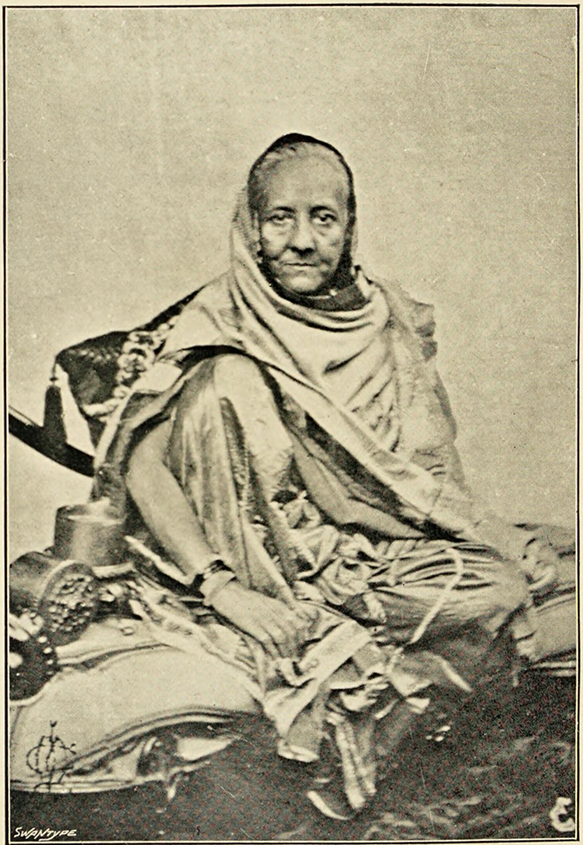

I did not think I would see it. During her colonial internment, Zinat Mahal, the last dowager empress of Mughal India, posed for the camera in 1872. The only photograph of Zinat Mahal known widely today is her individual portrait from that sitting. However, she decided specifically to pose with Emily Wheeler, a British memsahib who helped manage her custody. Since the empress rarely consented to being photographed, a double portrait would be significant. But if such a photograph existed, it was long lost. Archival catalogues no longer mentioned its existence.

Therefore, I was stunned to find the double portrait in The Connoisseur, a magazine for art collectors. The photograph was printed and circulated almost a century ago, in an issue from 1929. Scaled to be viewed in the palm of one’s hand, the portrait shows Zinat Mahal and Emily Wheeler sitting next to each other. They act like any well-to-do pair engaged in the awkward ritual of studio photography.

Internment images can be sites of compromised consent in different ways. The mug shot, for instance, formalizes a visual mode of compulsion at the start of the penitentiary experience. In the empress’s case, intersections of religion, class, and race coalesced in laws of veiling. The veil influenced if and how faces and figures were revealed to the camera and what happened to the plates and prints, write Deepali Dewan and Deborah Hutton in their book on Raja Deen Dayal. At the same time, the veiled woman was also an Orientalist figure on whom were projected ideas of duress, tradition, and sexuality. Consent is a knotty construct when it comes to a dispossessed Muslim royal in internment.

Scattered archival sources, from custody reports to provenance letters, note that Zinat Mahal refused to be photographed for a long time. Her internment manager, James Talboys Wheeler (Emily Wheeler’s husband), reported in March 1871 that she declined to be photographed when her family members did sittings. But then, she changed her mind, and negotiated enigmatic terms for her consent.

Zinat Mahal asserted that she would appear before the lens only if Emily Wheeler joined her in the portrait, as per a letter archived at the British Library in London. “For a long time the old lady refused to sit and then would only consent if my mother sat with her,” recalls Wheeler’s son in a letter from January 1921.“It seems that difficulty was experienced in persuading the ex-Queen to pose for her portrait, and that she only consented on the condition that Mrs. Wheeler sat with her,” repeats F. Gordon Roe, from family accounts, in The Connoisseur story.

Without trying to guess her motive, what is clear is that Zinat Mahal made her photographic consent conditional on a couple style of portraiture. The couple form enacted a relation, binding her and the unknown memsahib together forever. Intensely banal though the double portrait is, it emerges from a queer creative relation with the camera.

The difference between individual and group portraiture often has racial implications. Reading passport photos, especially Chinese head tax photos in Canada, Lily Cho suggests that the “emotional neutrality” ordered in ID pictures exemplifies not only what an ideal citizen “should look like but also what they should feel like.” State suspicion drives the neutral diasporic face. And, in the context of the United States carceral system, Nicole Fleetwood explores Black prisoners’ resistance to isolation as one of the “practices of survival.” Among such scenarios, Zinat Mahal’s refusal of the individual portrait is a refusal of solitary and suspicious forms of portraiture.

In the individual portrait, she adopts the same partial cross-legged pose and wears the same quiet attire as the double portrait, implying the continuity of a sitting. The creases indicate a makeshift backdrop. Alexander R. McMahon, an army officer, shot both portraits in the Wheelers’ drawing room in British Burma (now Myanmar).

Conquering Delhi and its rebellion in 1857, the British government secretly deported the empress and her family to Myanmar. They were detained there indefinitely and would die in near penury, petitioning again and again to return home. In fact, ordinary Muslim civilians, who were punitively expelled from Delhi for the 1857 rebellion, would not be issued permits to return for several years. Such colonial removals foreshadow the future threats of Indian citizenship being revoked from Muslims, such as those issued by the current regime.

The colonial government enforced anonymity on the deported royal family, labelling them “Delhi state prisoners.” This was done to prevent another anticolonial uprising to reinstate their sovereign lineage. Despite the rule of anonymity, the photographic interest in celebrity figures (spurred by the expansion of small portraiture technology after the 1850s) partly explains the desire to photograph Zinat Mahal, if only to be seen by high-ranking colonizers.

The custody report from August 1872 mentions McMahon’s photo session with Zinat Mahal. But it excludes any hint of a consent clause, a double portrait, or the memsahib’s presence. The exclusion confirms the nonconformism of the condition. Wheeler’s son surmises that the individual portrait was cropped from another group portrait. Zinat Mahal may not have known that she was being taken individually or that so many would see her in a form she refused.

As I say in my article “Protest Without End,” the double portrait stages nonconformism when revolution has failed. It makes visible a type of political satisfaction, one that arises in the absence of political success. Recent scholarship in feminist, queer, and antiracist methods treats the colonial archive as a domain of dissident possibility. Leela Gandhi, Saidiya Hartman, and Ariella Azoulay center ethics in archival research. Zahid Chaudhary focuses on how meaning is made between the body and the world; Tina Campt listens to how images sound; and Gayatri Gopinath cares for and about the unruliness of vision. This set of humanities methods has renewed interest in the effects, limits, and leakiness of subjugation.

The incarnation of photographic consent in the double portrait is not an antidote to Zinat Mahal’s dispossession. But it is a subtle and valuable alteration in the relations of extreme colonial force between those behind and in front of the camera.

0 Commentaires