SAGINAW, Mich. — At the beginning of my guided tour through the Blactiquing Space, collector and curator Kevin Jones asked me a provocative, challenging question: Can something be racist and also be beautiful? It was just the first of many moments that evoked conflicting thoughts and emotions during my experience of the installation of his decades of collecting racist and racialized objects (mostly) from secondhand stores. Perhaps one of the reasons it’s so difficult to have an honest conversation about race relations in the United States is that our collective attention span has become so compressed, we can hardly begin to pick apart a subject so incredibly fraught with nuance. But in using racialized objects as material evidence of the African-American experience in US history — and through his adamant and authentic attachment to them — Jones has skillfully prepared an experience through which no one can pass untouched.

The exhibition opens with “Grandma’s Room,” a bedroom-like installation that is tribute and shrine to the women in Jones’ life — including a bed covered in quilts made by his great-grandmother; walls covered in family photos; and a book of personal histories chronicling members the family since his great-grandfather’s birth in 1852; and post-emancipation move to Tuscaloosa, Alabama. This area serves as a kind of threshold between original works presented in the foyer, including a selection of drawings by Jones’ uncle, Melvin Hardy, who spent a lot of time in the country’s carceral system, and the “Black Christmas Tree” — an all-black synthetic tree decorated with packages of Skittles, water pistols, figures rendered in rope by artist Nyesha Clark Young, and ringed with a paper wreath bearing the names of 229 Black people killed by police between May of 2020 and May of 2021.

“I wanted to pay tribute to and recognize those lives,” said Jones. “Because I want Blactiquing Space to be an acknowledgment of Black lives.”

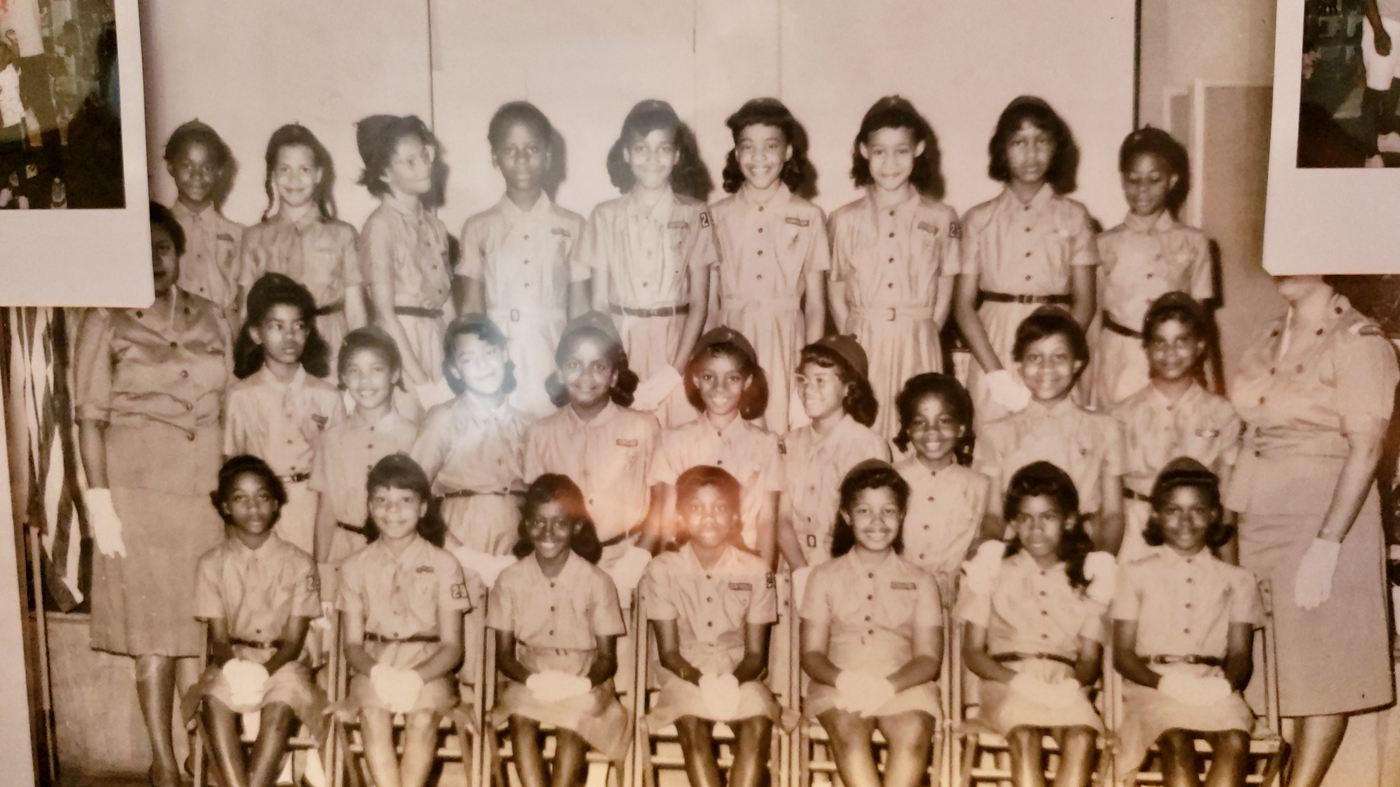

These pieces signify the highly personal nature of the collection that lies within the main body of the exhibition; one cannot reach the assortment of mass-produced racism without first passing through the veil of Jones’ highly personal and familial context. In this way, the Blactiquing experience instills a sense of conflict embodied in the objects — being disgusted or alienated by them, but loving and identifying with them, too. Over the guest book, Jones has mounted a vintage (apparently valuable) racist toy — a goonish face with exaggerated features whose eyes roll when you pull a string—and just below it, a beaming photograph of an all-Black Girl Scout troop. There is an uncomfortable leveling of the hierarchy between these objects — one gets the sense that Jones legitimately holds equal space in his heart for both of them.

This one-two combo is a move that will repeat itself throughout the nearly hour-long tour Jones gives me of the space. Objects are mainly grouped by similarity, with an area devoted to Africana, another to cotton-picking, watermelon tropes (Jones is dressed in a watermelon-themed button-down that he acquired on his recent trip to Hawaii), toys, and two sections on advertising materials. The back wall of the exhibition is anchored by a cube shelf showcasing dozens of Black dolls — handmade, commercial, old, contemporary, horribly racist, tender depictions, well-loved, completely untouched. There can hardly be a more literal proxy for people than dolls, and seeing these numerous and individual Black bodies stacked into cube spaces cannot help but evoke a specter of Middle Passage, or its contemporary echo, the prison system.

-

Aunt Jemima vs. Uncle Ben checkers -

A living room space for reading and reflection -

An Aunt Jemima box -

Selection from a shelf of Gold Dust washing powder. A twin himself, Jones finds particular resonance with this iconography.

Like the rest of the exhibition, the wall of dolls leverages the extraordinary power of presentation to create a mix of attraction and revulsion. As a neurodivergent viewer particularly prone to object repetition, many parts of the Blactiquing Space hold visual appeal for me in the arrangement of similar or same objects — the racist aesthetics of those objects notwithstanding. This represents a powerful bait-and-switch — being drawn, say, to the symmetry of a shelf lined with high-gloss blackface caricature busts, to have Jones reveal them to be a collection of “Jolly N***** Banks” designed to swallow pennies. And then to have him mention that one of them used to belong to his own grandmother, as a fixture of her home.

Obviously, the Blactiquing Space presents differently as the collection of a gay Black man who handles these deeply fraught objects with such emotion, connection, and care. One cannot imagine such a collection being acceptable or appropriate in other hands. But even with Jones’ commitment to his collection, the emotional drain of walking people through the experience is inescapable. Because inevitably, as we moved through the room, the tour became confessional. Surely no one can visit the Blactiquing Space and avoid recognizing something that strikes a chord. In my own work, I created and presented a 1:12 scale hoarder dollhouse, and people felt safe to tell me their personal and familial hoarding stories. It takes little imagination to guess what kind of stories Jones has heard throughout the run of his exhibition. He has not just created a space to show objects; he has created a place to have the most crucial and difficult conversation facing our society in crisis.

There is uncanny power to the Blactiquing Space: these objects will be seen because Jones wants you to see them. First, he rescues them from obsolescence or destruction; then, he leverages the tools of consumerism to arrange them into eye-catching displays; finally, he walks you through them to make sure you never look away. Ultimately, he seems prepared to receive what revelations may come as, confronted with an inarguable wealth of evidence; each visitor rises to a new level of identification and accountability within the tradition of racism upon which our country was built.

0 Commentaires