HANNOVER, Germany — Where do I come from or, more broadly, on what is human existence founded? In Mother Tongue at the Kestner Gesellschaft, French artist Camille Henrot makes visible those aspects of motherhood and maternal labor that are suppressed into invisibility in much of Euro-American society.

The subject of motherhood in art is not blessed with many examples. What images exist outside of idealized Christian depictions of Mary with the Christ child? In our visual culture, this topic has been marginalized almost to the point of taboo. Henrot — a multimedia artist who works in painting, drawing, sculpture, and video — challenges unquestioned, idealized, and traditional representations of motherhood and clichés of maternal happiness, and demonstrates the need to look at the beginning of our very existence to address social and gender inequalities.

With the paintings “Untitled (soon)” and “Wet Job” (both 2019), Henrot reflects on the invisible image, of the reality of motherhood and the unborn child, in different ways. The former recalls ultrasound images taken during pregnancy. Using ink on soaked paper she evokes the physical environment of the womb. Boundaries become blurred, polarities of inside and outside are taken up thematically as well as visually. Watercolor lines snake through the picture. As the motif oscillates between visibility and hiding, it suggests a shy hybrid creature searching for its form. The kind of coming-into-being that Henrot achieves in the work seems almost about the autonomy of the line and the creative process itself.

The figurative “Wet Job” depicts a woman using a breast pump, painted over a watery, reddish-pink ground. How often, if ever, has anyone seen a breast pump portrayed in art? In an interview with the exhibition’s curator, Julika Bosch, Henrot notes that it was hard to find a good reference for the image, and that there is an absence of these images in society. The machine illustrates the aspects of work, labor, pain, and depletion that are typically unacknowledged parts of motherhood. The breasts are in pain if they are not emptied and the child must be fed; the maternal body becomes a kind of machine.

Conversely, and ironically, the pump enables women to work and gain some independence from their roles as mothers because they don’t have to be immediately available to the child.

As Henrot explained on the website Topical Cream,

The breast pump, as an object, started to carry the expectation of the woman as an endless resource who could produce at all hours of the day in any setting. But because this labor is uncompensated, taboo, and even considered illegal in certain public settings, the mother’s milk could be considered an abundance that society does not have to pay for, or even look at.

In fact, several paintings in the exhibition are visual explorations of breastfeeding, ambivalent expressions of the desire and fear of being eaten and conflicting needs of bonding and separation. The deformation of breasts, the pain of nursing, and the interdependence of the caregiver and child are made palpable in works such as “Eating Tea” and “What Did U Say” (both 2019). The exhibition’s title, Mother Tongue, refers to language but it is also represented quite literally here by the physical connection between the mother and the tongue of the baby.

In this context, the intense red of the paintings adds a sense of brutal physicality and emphasizes the violence of the relationship between mouth and breast that is sublimated in most artistic portrayals. According to Henrot, the red tone is actually based on the inside of the eyelid as we see it when we look into the light with our eyes closed. The veins and blood of one’s own body become visible.

During the pandemic she created a series of works in this shade of red, titled Is Today Tomorrow, which addresses the lost structure of the day and disrupted conception of time. At the end of the long corridor lined with several red, small-format paintings that metamorphose between figurative and abstract, is a yellow painting, which marks the close of the series. The eyes open, the red vanishes, and the gaze falls on a bright picture with the programmatic title “Time for Change,” which depicts two figures merged into each other.

As the exhibition title suggests, language is central to Henrot’s work. She creates a list of titles first, and then starts drawing, finally looking at the list again and assigning them to the appropriate paintings. Titles in Is Today Tomorrow are: “A day for us,” “Tomorrow will be a better day,” “Wednesday morning,” “Lockdown day,” “Day of milk,” “A long day,” “Play day,” “A Sunday kind of love,” “Blue Monday,” “The day we realize,” and “Wait another day,” “Plain as day,” “Day of drifts,” and “Time for change.” Together they mark the passage of time.

The most prominent work in this room is the large sculpture “3, 2, 1” (2021). A crow-like form with breasts, shedding a tear, rises from the center of a platform, like a phoenix from the ashes. The “ashes” resemble a garbage dump composed of remnants of Henrot’s artistic creations from the foundry. The garbage nest points to the connection between creation and waste that refers to our collective decline because of human consumerism as well as the burden of the mother who creates in a world overflowing with waste. Henrot based the sculpture on the German term Rabenmutter (literally translated to English as “raven mother”), a term for a bad mother (it’s worth noting that there is no equivalent term for father or a caregiver in general). The title “3, 2, 1” can be understood as a countdown toward a (potentially self-made) state of urgency. These works undermine the ideal of a mother or caregiver, in part by converging nature and animals with human beings, and by depicting gender and even species as fluid.

The ribbon, a symbol of connection and fluidity, recurs throughout the exhibition. Henrot writes the titles of the works on illusionistic ribbons painted on the walls, which seem to fly through the room, with a lightness that suggests a heavenly sphere. She even picks up on the theme of connection sardonically with the telephone cables in the sculpture “Two on Call” (2020). In “L’enfant Plus” (2019) a ribbon encircles and connects with a rotund torso with squat legs. An image of pregnancy in the background seems to ask: where do I end and the other begins?

Henrot’s bronze sculptures call to mind those of Henry Moore or Constantin Brâncuși, although this sculpture recalls Hans Bellmer’s “poupees” (dolls), and their violently misogynistic undertones. The backside of “L’enfant Plus” is a plump butt, cheekily thrust out at the viewer. It may be a sly commentary on the modernism of Moore and Brâncuși, but it also seems like a surprising allusion to the putto in Renaissance art: the missing chubby cherub who should be holding up all the flying banderoles, and without whom the messages float aimlessly.

She further emphasizes the illusion of an ideal and erasure of the work of motherhood through oversized half-shells that jut out from the wall near the domed ceiling. The shells evoke Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” (c. 1484–86); the absence of the glorified and idealized female body, as symbolized by the canonical Venus, raises the question of what is actually erased by the woman/mother ideal.

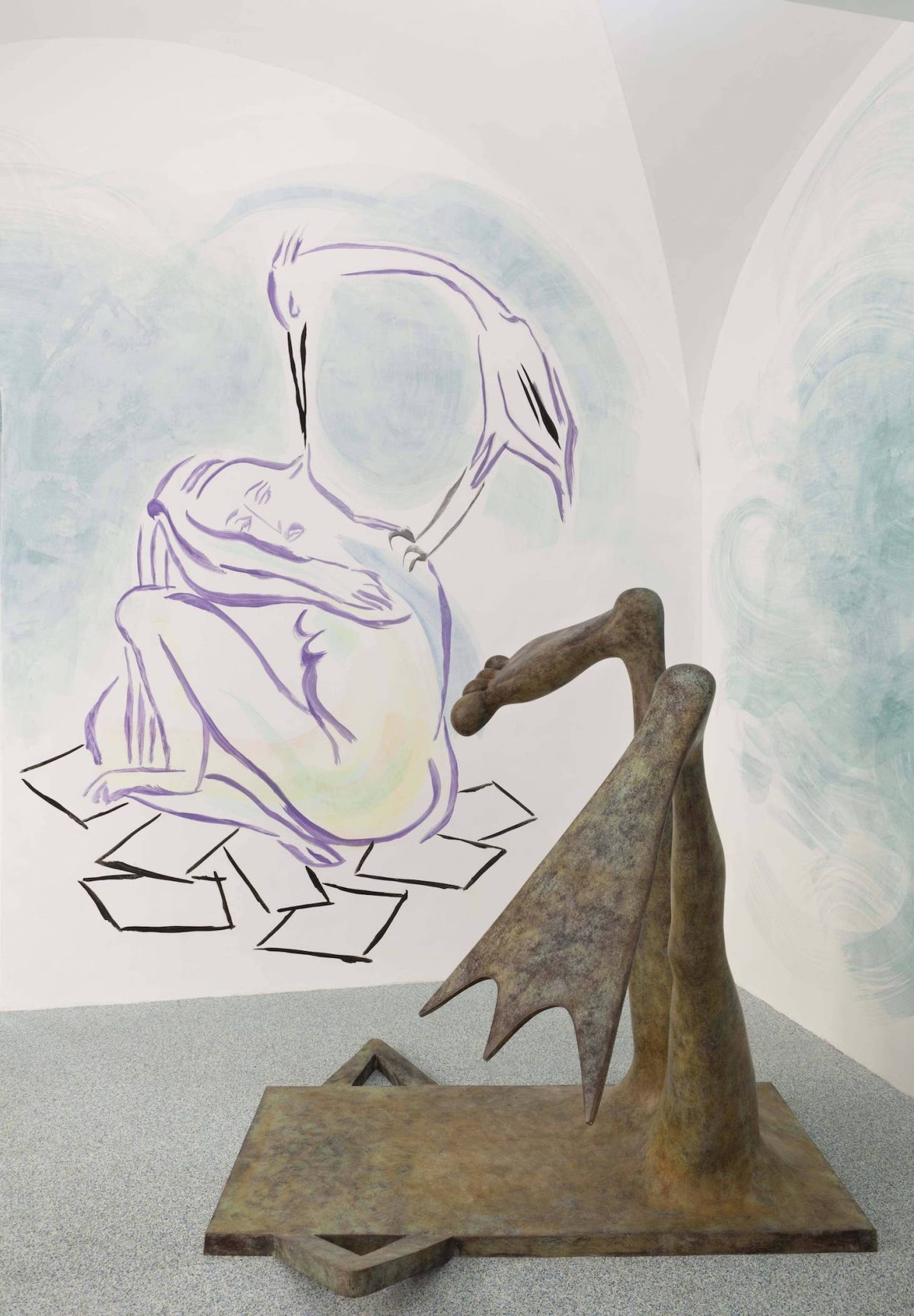

The last room forms a chapel lined with seven frescoes (Monday series, 2016). The ecclesiastical is embedded in the form of the fresco — frescoes are rarely found in contemporary art — but religious and mythological motifs are also apparent in the content and titles, joined with banal subject matter. One work is titled “Uneasy Moses.” Another conflates the Christian Annunciation with the myth of the stork delivering babies. A stork perches on the back of a seated woman and picks at her ear with its beak, both rendered as purple line drawings.

In Christian mythology, purple signifies the kingship of Jesus and the ear is connected to Mary’s conception through hearing the word of God. Henrot seems to propose that both myth and religion taboo the origin of life through sexuality and birth. The religious references interweave motherhood and heavenly creation through a narrative of chaos and melancholy that begins with Monday.

Mother Tongue impressively traces the many levels of our human existence back to birth through the mother. As Henrot points out, inequalities cannot be corrected if we do not completely change the way motherhood is perceived; in an interview with the curator, she stated that motherhood “needs to be desacralized, it needs to be almost dissociated with gender, it needs to be more integrated into the economy and labor structure.” In this light, “3, 2, 1” gains increased urgency — time is up; time for change.

Camille Henrot: Mother Tongue continues at Kestner Gesellschaft (Goseriede 11, 30159 Hannover, Germany) through August 8. The exhibition was curated by Julika Bosch.

0 Commentaires