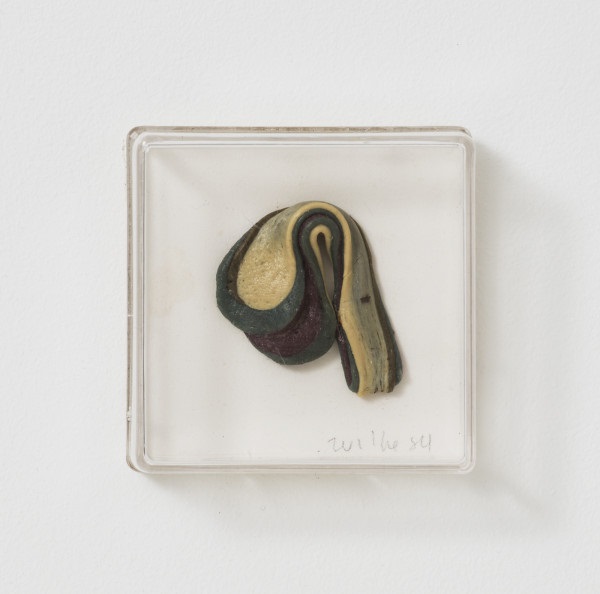

If, for some reason, anyone ever needs to forensically profile an audience that attended a Hannah Wilke performance in the 1970s, they could start by swabbing her chewing gum sculptures. The bite-sized artworks — over a dozen of which are now preciously displayed in plexiglass shadowboxes at a Wilke solo exhibition at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation — preserve both the salivary DNA of strangers and a rainbow of artificial coloring.

“God bless America, it’s no longer just pink gum, but blue, purple, yellow, black, white, and green gum,” the American multimedia artist recalled in the mid-1970s about shopping for gum, because she wanted to colorize the gray kneaded eraser sculptures she was working on. “One could double fold different gums so that the internal and external colors are different and each side is in a different color. The center becomes a line of a third color. It is a sophisticated way of color naturally forming itself.”

Wilke’s gum sculptures are bent into arches that look too artfully molded to be stuck under a school desk, but are also of the familiar stuff of childhood. Her experiments with gum began in 1975 and stretched on for years into feminist and conceptual performances and photography, forming part of an elastic history of bubble gum as an art medium that started before her and continues to this day.

Other artists have used gum as fodder for photographs, or as miniature sidewalk canvases, but Pulitzer Arts Foundation curator Tamara Schenkenberg argues that for Wilke, gum was part of her overall practice of working with the soft and pliant. “Wilke used these malleable materials to distill the motion of her hand and convey movement — the concept of gesture is so important in her work,” Schenkenberg said. “But chewing gum also has some unique properties as a sculptural medium that Wilke was drawn to, namely its wide range of bright colors and also its sweetness.”

This quickly fading sugariness, an invisible but inherent part of the gum artworks, held meaning for Wilke. “I chose gum because it’s the perfect metaphor for the American Woman,” Wilke explained. “Chew her up, get what you want out of her, throw her out and pop in a new piece.” This throwaway element is reflected in her S.O.S. Starification Object Series (1974–82), a series of photographic self-portraits and public performances where Wilke handed out gum to her audience, asking them to chew it and give it back. Then she’d sculpt the wads into vulvar shapes and stick them to her topless body as a critique of the commodification of women.

Research hasn’t yet revealed whether Wilke knew that another artist, Alina Szapocznikow, had used chewing gum just a few years before. “I sat down and began to dream, chewing mechanically on my chewing-gum,” the Polish sculptor recalled of a lazy Saturday around 1971. “While I was pulling astonishing and bizarre forms out of my mouth, I suddenly realized what an extraordinary collection of abstract sculptures was passing through my teeth. It suffices to photograph and enlarge my masticatory discoveries to create the event of a sculptural presence. Chew well and look around! The creation lies between dream and everyday work.”

Szapocznikow documented her masticated sculptures in a series of around 20 black-and-white photographs called “Fotorzezby Photo Sculptures” (1971), where gum chewed into fantastical shapes was propped on a ledge or plinth and shot close-up. There’s a comical disconnect between the high-brow formality of these arty photos and the material itself, usually bought for change at the corner store.

Decades later, American photographer Michael Massaia also made a photographic series using chewed gum, creating portraits of single-piece sculptures mounted on black plexiglass. He started using gum around 2015, after he finished photographing a series of melting ice cream pops, and wanted to work with another medium from his childhood.

“It all starts with finding the right gum, and chewing it for a while so it gets the proper texture,” Massaia explained to Hyperallergic. “It astonished me how you could sculpt anything from a human heart (with all the visible vessels etc.) to imaginary sea creatures. It seemed like the chewing gum was able to achieve a level of dimension and reality that could not be achieved via any other medium.”

When asked what brand of gum works best, Massaia answered unequivocally: Big League Chew. Hubba Bubba is good for color.

Italian sculptor Maurizio Savini, on the other hand, strictly uses classic pink bubble gum for his monumental sculptures and doesn’t chew it (he’s confessed that he doesn’t even like the taste of the stuff). Savini and his assistants receive the material unwrapped and in bulk, straight from a factory, and soften it with hot air. Savini then uses the gum to coat fiberglass sculptures — of crocodiles, human figures, and machine guns — before spraying them with a preservative formaldehyde cocktail. As opposed to Massaia’s and Szapocznikow’s single-piece sculptures, or Wilke’s handful of sticks per artwork, a Savini sculpture can call for 3,000 gumballs a pop.

But apart from being sculpted, and then maybe photographed, dried-up wads of bubble gum have also been used as blank canvases for paintings. For over a decade, British outsider artist Ben Wilson (aka “The Chewing Gum Man”) has spent his days crouched on London’s Millennium Bridge or elsewhere in the city, painting in-situ miniatures on gum stuck to sidewalks. Wilson estimates that he’s created at least 600 paintings on Millennium Bridge alone, using his toolkit of tiny brushes, acrylic paint, and lacquer.

“I’m trying to embrace the very thing that people have rejected. They’ve just spat it out,” Wilson explained in a video interview. “I’m taking that and then utilizing it in a constructive way. So that’s a celebration of creative thinking. Finding different ways of making thing happening.”

Bubble gum has been part of pop culture for decades, but its art historical record is still relatively undigested. As exhibitions like the current Wilke show spotlight artworks made with this polymeric nosh (with her gum sculptures likely among the oldest that still exist in the round, instead of strictly on film), maybe art history’s sculptural bubble will expand to include objects made with Juicy Fruit and Big Red alongside those made of marble and bronze.

Hannah Wilke: Art for Life’s Sake continues at the Pulitzer Art Foundation (3716 Washington Boulevard, St. Louis, Missouri) through January 16, 2022.

0 Commentaires