CHICAGO — Can abstraction be a language? If you put the question to Caroline Kent, whose exhibition Victoria/Veronica: Making Room occupies two rooms at Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art (part of the MCA’s Chicago Works series), I imagine her answer would be something like “almost.” The show — which combines wood sculpture, repurposed furniture, abstract paintings, mixed media works, and the negative space of shaped recesses in the gallery walls — takes the elusiveness of communication as its theme.

Kent has been interested in the relationship between language and abstraction for some time. Her earlier output, for example, includes what she calls her “typewriter works.” These are small abstract paintings on paper, which she feeds through old typewriters, adding text beneath the images. The texts call out for context: they read like fragments from a missing narrative, and their relation to the painted shapes and brushstrokes above them is always ambiguous. The works call upon viewers to fill in the missing information, to bridge the gap between words and images. In essence, we find ourselves in a Surrealist game, trying to make communicative sense out of materials that tease us with the possibility of meaning. It can feel like reaching out to someone who is also reaching out to us, and almost connecting. When most successful, the pieces go beyond the level of Surrealist game-playing and become poignant reminders of the tenuousness of human connection.

Painting is Kent’s primary focus, and she is best known for large abstract works painted on a background of black gesso, often hung unstretched on walls where they flutter slightly, like banners. She creates them by cutting shapes from paper and rearranging them until she finds a satisfying composition, then she paints hard-edged abstract forms on canvas. The approach owes something to Russian Constructivism and something to Matisse’s late-period collages, and her preferred shapes evoke the visual vocabulary of Ellsworth Kelly, although her canvases are square or rectangular. Lines — curved, dotted, or gestural — weave across the picture plane, softening its severity. A beautiful, painterly facture also softens the hard-edged shapes, which rarely have the austerity of flat color — and the pastel palette Kent uses pops against the black gesso backgrounds. As a formalist, she knows what she’s doing, and does it well.

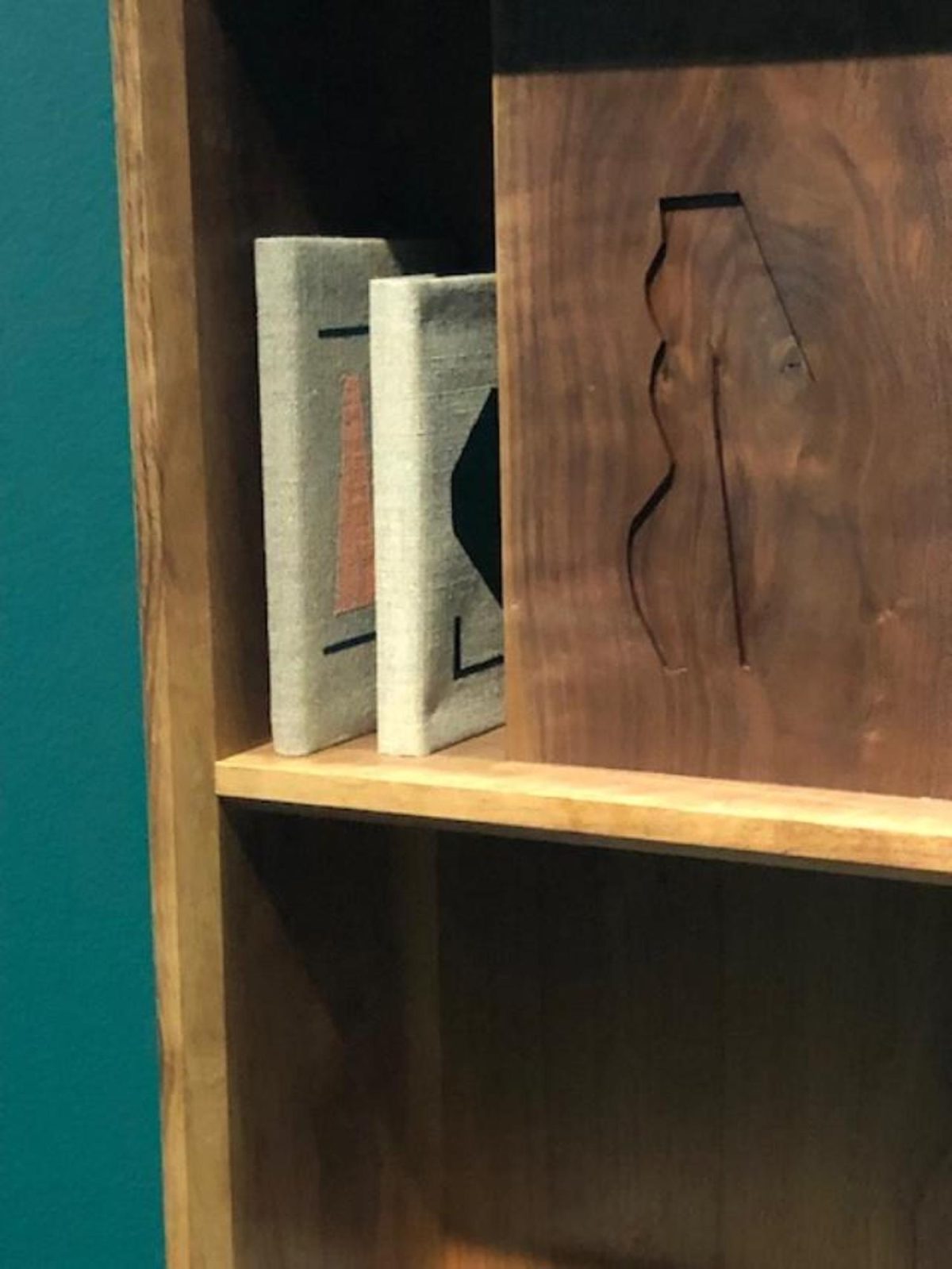

The strongest individual works in the show have all the hallmarks of Kent’s previous large abstract paintings: pastel forms and a variety of lines on black gessoed canvases hang loosely from the walls, the palette dominated by soft greens, grays, and peaches. When different colors overlap Kent really gets to show off her skill at handling acrylic. While these paintings reward close attention as individual works, it is the context of the surrounding installation that makes them truly exciting. The show is arranged in two rooms: an outer one opening onto the museum’s main third-floor corridor and an inner one, dimmer and more intimate. The outer area includes paintings, but also two wood sculptures that could almost be mistaken for stools or end tables, as well as a bookshelf complete with hardcover books and carved wood panels.

The forms and colors on the book covers pick up on the shapes in the paintings, as do the shapes of the panels, and the wood sculptures are made from boards cut to reflect the painted shapes. Mixed media pieces on the walls combine paintings with concrete panels, on which the geometric forms we see on books and paintings are repeated with minor variations. Indeed, as one looks around the gallery, it becomes clear that shapes on the different pieces aren’t identical to one another, but have something like a family resemblance. Repeated with variations in different media, they feel like translations of one another, or like a phrase whispered in the ear and passed on via another whisper, morphing as it travels from person to person. Is this communication? Almost.

The interior room reveals another dimension to the installation. It includes more paintings with similar shapes to those in the outer room, as well as lines and dots, some reminiscent of Morse code, others more like the para-calligraphic markings found in much mid-century Persian or Turkish abstract art. Everything hovers at the brink of signification, without quite crossing over into denotative meaning. Large sections of the walls are cut away with recesses that further echo the shapes in the paintings. One recessed space, “Silent Sentinel 1”(2021), contains a painted concrete slab whose shape mirrors those pressed into concrete in a piece in the outer room. The installation practically vibrates with the energy of near-connection and near-signification. It is fitting, given this emphasis on communication, that the central feature of the inner room is a wood writing desk, complete with books whose covers visually echo the books on the shelf in the outer room.

In crossing from the outer to the inner room, Kent moves viewers from a space of reading to a space of writing: two poles of a process of mediated communication. Wall texts that she has written confirm this impression. The exhibition, we read, “explores the intimate correspondence between a fictional set of identical twins who communicate telepathically across two domestic environments: a writing room and a reading lounge.” The twins “are united by their shared, secret language. Traces of their conversation appear in the form of abstract shapes that move across the surface of drawings, paintings, objects, furniture, and walls.”

Kent is a twin herself, and it is perhaps relevant that she and her twin developed a kind of private language while growing up mixed-race in overwhelmingly white downstate Illinois. But the text is the least interesting part of the installation. Unlike the textual parts of her typewriter works, it limits, rather than expands, the scope of interpretation. Surrounded by visual evocation, it comes across as very literal, offering an explanation for art that works exceptionally well without one.

Victoria/Veronica: Making Room continues at the MCA Chicago (220 East Chicago Avenue, Chicago, Illinois) through April 3, 2022.

0 Commentaires