In 1976, artist Mierle Laderman Ukeles wrote a letter to the commissioner of the New York City Department of Sanitation. Attaching a clipping from a review regarding her collaboration with over 300 maintenance workers in a building downtown, Ukeles asked: Would the department be interested in an artist-in-residence? The unprecedented relationship that resulted had staying power, as Ukeles has been an official artist-in-residence with the city’s sanitation department for over four decades. In 2015, in the spirit of Ukeles and her radical notions of public art, New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs launched the Public Artists in Residence (PAIR) program, which embeds artists in various municipal agencies, from the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (Tania Bruguera, 2015) to the Civic Engagement Commission (Yazmany Arboleda, 2020).

Julia Weist, one of four 2019–2020 Public Artists in Residence, was paired with the Department of Records and Information Services (DORIS), which is tasked with preserving and facilitating access to city records going back centuries. The millions of records in DORIS’s holdings are largely unprocessed and undigitized. Weist, whose background in information and library sciences informs her artistic practice, dedicated herself to parsing the relationship between the city and its artists as documented in these vast municipal archives. Now, prints from her project Public Record (2020) have been acquired by several major museums, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Brooklyn Museum.

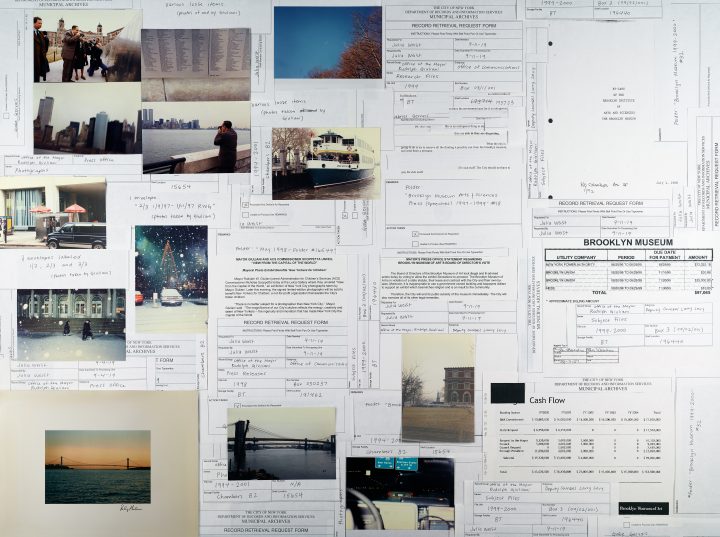

Weist made 11 photographic prints from her archival findings, creating compositions from found images and texts partly obscured by the retrieval slips that made them locatable. Each print zeroes in on a different theme, from defining art — “The arts are a labor-intensive industry characterized by chronically high unemployment and underemployment,” a line in “Definitions”(2020) reads — to critiquing it — in “Critiques” (2020), some panelists found Faith Ringgold’s work “engaging” while others described it as “depressing” and “ethnocentric.”

In an essay on Public Record published by n+1 in May 2020, Weist ruminates, “While it’s undeniable that New York’s municipal government has historically understood the value that art offers the city, it was less clear, in my research, what the city offers back to artists … The collection is exhaustive in its documentation of art workers struggling to survive in the city.”

To ensure that the prints, made from and about archival material, entered the archives themselves, Weist cannily used city-owned equipment and the aid of city agency employees to produce them. She also transferred a copy of each print to the DORIS Commissioner along with a memo, securing their place in the Agency Head General Subject Files. In response to Freedom of Information Law (FOIL) requests filed by the participating public, DORIS made the artworks digitally available via New York City’s Open Records portal, effectively exhibiting them as public art in the commons of nyc.gov. (You can view the works by searching “Julia Weist” on the portal.)

While most of the museums that have acquired prints from Public Record have been concentrated in New York, the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Art acquired “International” (2020), an exploration of monuments, and the MIT List Visual Arts Center in Cambridge, Massachusetts added “Rubrics” (2020), in which works of art are ranked on a point scale, to its collection.

The Queens Museum acquired “Role” (2020), about the municipal government’s perception of the function of art in society. “Limits” (2020), which analyzes where the limits of the city government lie with regards to regulating art, entered the holdings of the Jewish Museum in New York. (“The Statue of Liberty is under the jurisdiction of the federal government,” a memo in “Limits” states.) Governmental overreaches rather than limitations crop up in “Demonstration” (2020), which was acquired by MoMA. In addition to documenting artist protests, some of which were held at MoMA, the print logs efforts by NYPD intelligence to surveil artists. “Film work for Russia,” a handwritten note reads ominously.

The Brooklyn Museum acquired “Giuliani” (2020), which features photographs taken of and by former New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani, and, even more bizarrely, an exhibition announcement for a show of his photos in 1998. The print also highlights other instances of Giuliani’s involvement with the arts, such as his vehement efforts to shut down the Brooklyn Museum in 1999 over the Sensations exhibition, which included Chris Ofili’s “The Holy Virgin Mary”(1996), a depiction of the religious icon that incorporates elephant dung. One partially blocked-out memo in “Giuliani” reads: “It offends me … so called works of art … What the city is going to do is try to remove all the funding it possibly can from the brooklyn museum [sic], and send them a message.”

Writing in n+1, Weist says: “While it may not help us now … to know that a previous Mayor was a terrible photographer, there’s much more to find in the records than Giuliani’s photographic outtakes. These records illuminate where power and resources have pooled or been withheld, and tie history to daily life.”

0 Commentaires