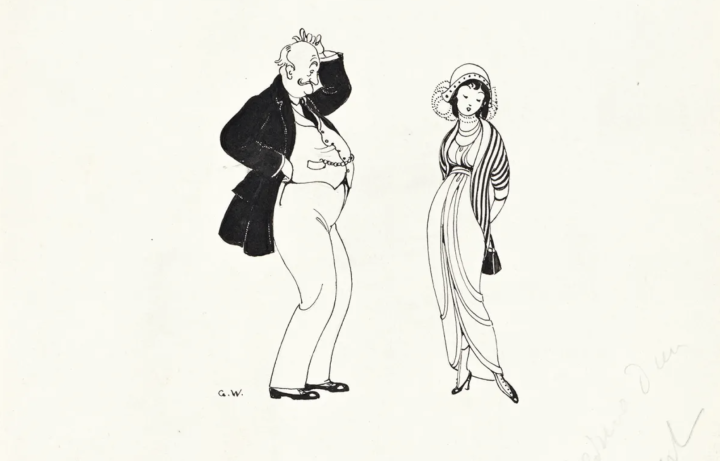

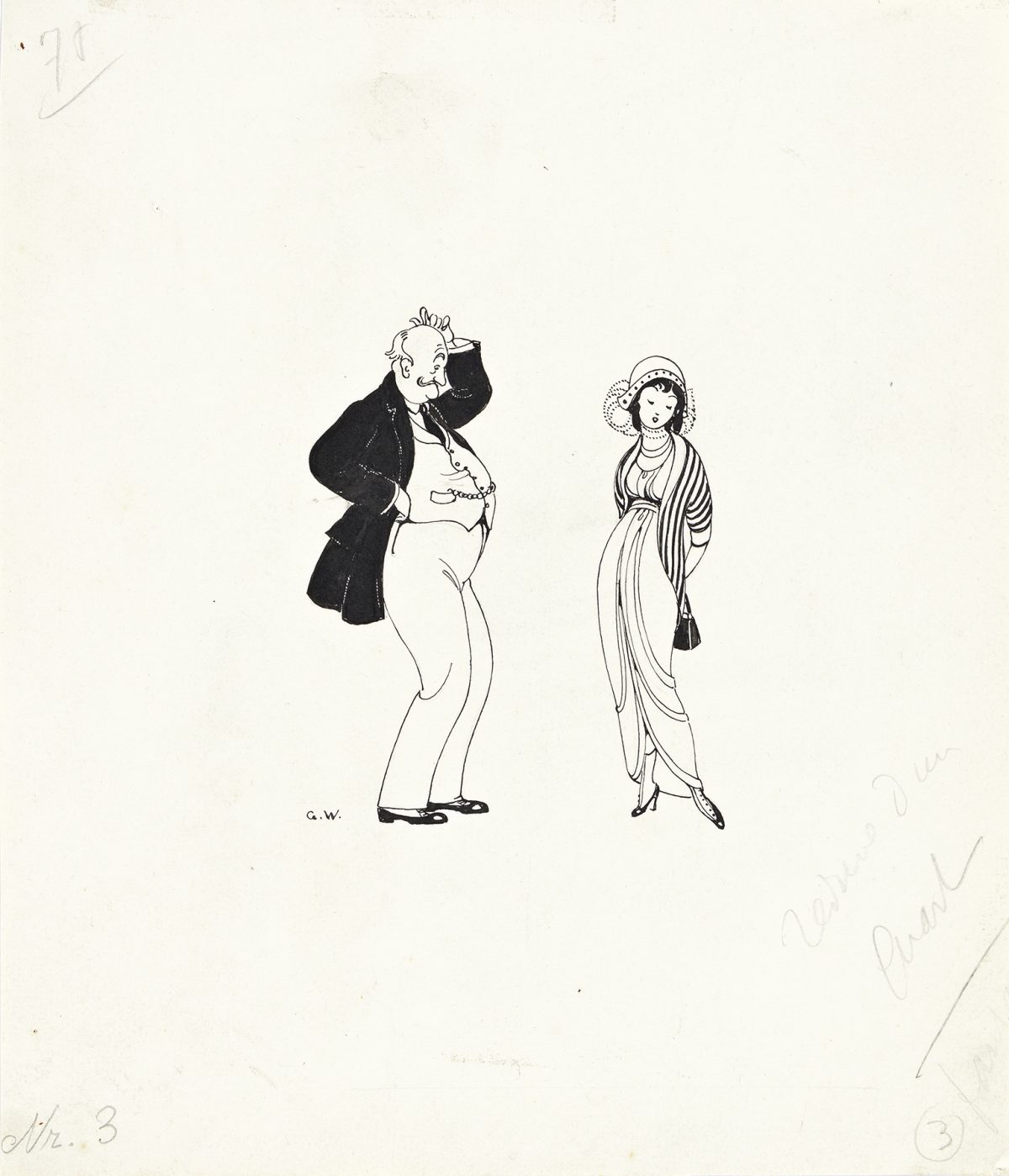

In art and life, early 20th-century painter, illustrator, and cartoonist Gerda Wegener (1886–1940) upended binaries with aplomb. Working in a signature style that was part Art Deco and part Art Nouveau, the Danish-born artist explored fluid notions of beauty, pleasure, and identity. Her elegant works on these themes ranged from glamorous portraits of her partner Lili Elbe — one of the first people in modern history to undergo gender-affirming surgery — that were exhibited in the salons of Paris and even purchased by the French state, to graphic illustrations of sex that celebrated women’s pleasure and featured in Casanova’s memoirs or books of erotic poetry. Though Wegener largely faded into obscurity — her aesthetic fell out of fashion in her lifetime, and in her final years she sold postcards for a living — there has been a resurgence of interest in her life and work in recent years, perhaps most prominently in 2015, when she was the subject of an exhibition at Copenhagen’s Arken Museum and appeared as a supporting character in the Oscar-winning film The Danish Girl. (This week, the actress who played Wegener responded to some of the criticisms levied at the 2015 film, which cast a cisgender actor as Elbe.)

Wegener (née Gottlieb) grew up in Grenaa, a town on the Jutlandic peninsula, where she was the daughter of a pastor. As a teenager in 1902, she left for Copenhagen to study art at an annex of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts that admitted women. Five years later, she made a splash in the Danish newspaper Politiken, which published an article by Symbolist painter Gudmund Hentze criticizing popular depictions of people in the countryside, executed by what he and others called “peasant painters”. Hentze instead gave an impassioned defense of Wegener’s “Portrait of Ellen von Kohl” (1906), a highly stylized painting that had been rejected from both the official gallery of the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts and the gallery of the Association of Danish Artists. A spate of articles and discussion followed, with people alternately praising and denouncing Wegener’s skill and aesthetic. Wegener never commented on the whole affair, but she did go on to win the newspaper’s drawing competition, on the theme of “the Copenhagen woman,” the following year.

Women — typically modern, bobbed, and lithesome — were a central motif for Wegener, who had sexual relations across the gender spectrum. Among her most recurrent models was Lili Elbe. Gerda met her husband, a landscape painter, as an art student in Copenhagen; the pair wed in 1904. Initially at Gerda’s urging, her partner posed as a stand-in for a Danish actress who was unable to attend a scheduled sitting for a portrait. Soon, however, Lili was regularly posing for Gerda and began to exist outside of the studio, as well. When Gerda was invited to exhibit her drawings of Lili in Paris in 1912, the couple — or, as Lili put it, “the three of us” — relocated from Copenhagen to Paris, where Lili was able to live as a woman, self-fashioning as she pleased.

In Denmark, a major cultural critic had called Wegener’s drawings “Gerda Wegener’s sleazy regiment.” In France, however, the artist found commercial and professional success. She won two gold medals — and one bronze — at the French Pavilion of the World Fair in 1925, and from 1923 to 1932 the French state purchased three of her portraits, which can be found today in the collection of the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris. Commissions, too, were frequent. In addition to designing glass mosaics for wealthy clients and making advertisements for feminine products including stockings and face cream, Wegener regularly illustrated magazines such as La Vie Parisienne, La Baïonnette, Le Rire, and even the limited-edition, high-end culture magazine Journal des Dames et des Modes, where her pochoir prints appeared alongside those of leading illustrators such as Umberto Brunelleschi and Georges Lepape. In the midst of painting portraits and making colorful fashion plates, Wegener drew erotic illustrations, many of which took Lili as a model. In 1925, for example, she collaborated with French poet Louis Perceau to elaborately illustrate Les Délassements d’Éros, a book of poetry, with watercolors that featured lesbian and queer sex, often among androgynous or chimerical figures.

When Elbe began exploring options for gender-affirming surgery in the late 1920s, Wegener was supportive emotionally and financially; she leveraged her considerable success, selling work to raise funds for the operations that would take place in 1930 and 1931. (Sadly, Elbe, who wanted to be a mother, died after an attempted uterus transplant in 1931.) In a pseudonym-laden letter to a friend from January 1930, Elbe excitedly reported on a consultation with a surgeon:

Grete (Gerda) and I believe we are dreaming, and are fearful of waking. It is too wonderful to think that Lili will be able to live, and that she will be the happiest girl in the world… Without Grete I should have thrown up the sponge long ago.

For Wegener, it seems, queer pleasure was an expansive, elastic concept: one that involved the complex joys of forging and finding one’s identity in the spheres of art, sex, sexuality, and gender, while adamantly supporting others in their journey to do so.

This article, part of a series focused on LGBTQ+ artists and art movements, is supported by Swann Auction Galleries.

Swann’s upcoming sale “LGBTQ+ Art, Material Culture & History,” featuring works and material by Tom of Finland, Gerda Wegener, Keith Haring, Diane Arbus, Peter Hujar, JEB, and Robert Mapplethorpe, will take place on August 19, 2021.

0 Commentaires