“It can be easy for black people to believe, about themselves and each other, the fabrications of white culture …. As a result, many of us are always and already performing in the direction of liberation, performing the mundane.” – Anaïs Duplan, BlackSpace: On the Poetics of an Afrofuture

ST. LOUIS — So often that it can feel inevitable, the creative output of BIPOC artists and makers is framed in the art world and broader cultural spheres strictly through what it resists or refuses: the overwhelming “specter of whiteness,” as Sherrow O. Pinder has put it, whose invisibility, for AnaLouise Keating, “is [its] most commonly mentioned attribute.” But what might it mean to refuse that framework entirely? To imagine a future unfettered by whiteness as the dominant norm?

Afrofuturist art and literature have long explored the liberating power of such a future, typically within a spectacular backdrop of space-age travel, technological marvels, and fantastic lands exploding with color. It is in a consciously anti-spectacular mode that curatorial collaborators Katherine Simóne Reynolds and Anaïs Duplan created the Self Maintenance Resource Center, on view at the Luminary Arts Foundation in St. Louis through July 24, and available as a digital microsite thereafter.

A physical iteration of a virtual project launched by Reynolds last year, the SMRC functions less as a traditional exhibition of completed artworks than as a living archive of personal, creative, and intellectual inspiration for the six QTPOC artists invited to contribute: Marquis Bey, San Cha, Naima Green, Evan Ifekoya, Kameelah Janan Rasheed, and Tabita Rezaire. What might it mean, the show asks, to wade through the waters of everyday creative collision and convergence? To document loss and love in this way? How might such an exploration, as Duplan puts it in his 2020 volume BlackSpace, “requeer so-called reality”?

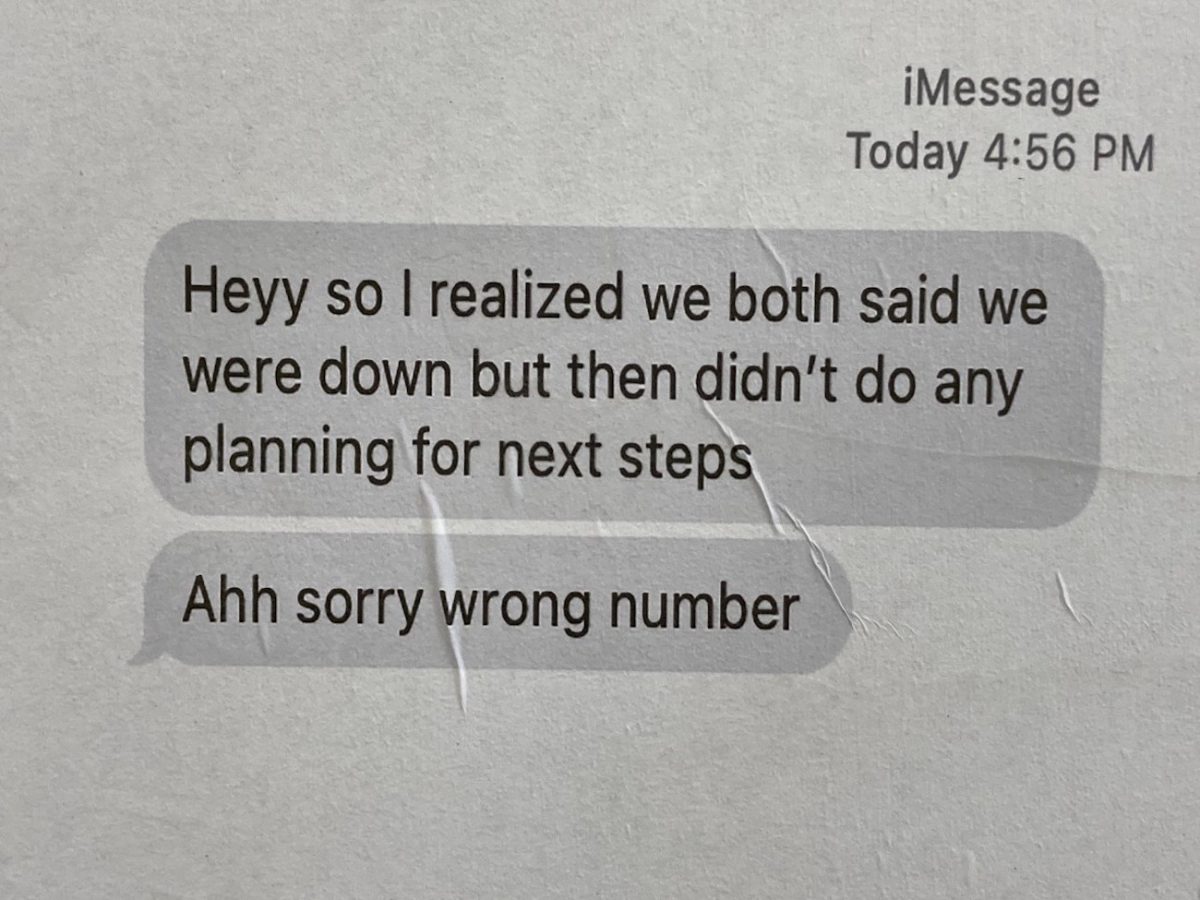

Materials that speak — directly, indirectly, and, in some cases, with delightful idiosyncrasy — to the interstices of artistic production and themes of romantic love and desire are submitted by each artist and rotate on a weekly basis. These range from videos and search engine results to iPhone snapshots and text messages. Each week of the exhibition, Reynolds intuitively arranges new material throughout the gallery, collaging and wheatpasting printed media onto visible surfaces, and draping pages sculpturally over speakers and on the ground. A tender iMessage exchange appears above footage of the Guyanese rainforest; a Google image search for “black leisure,” depicting a number of black futons and a dearth of human beings, is displayed across from a poster of a nose and glossy lips, with the text “HOW MIGHT YOU DO THINGS DIFFERENTLY TOMORROW?” printed in a boxy fuchsia font.

At times, these materials suggest the dissonance between QTPOC lived experience and media representations; others express the intimacy exchanged via daily conversation. Tensions between public and private flow between the visual and textual allusions in the show. “What does consent mean for an archive?” Duplan posed as one of the SMRC’s central inquiries. “What would it mean to have to ask for consent in order to see what its contents are and to demand a more embodied space, to crack open the way that archives usually work in terms of topicality and exclusivity?”

Originally conceived as an online project by Reynolds and Kalaija Mallery during the summer of 2020, amid a relentless pandemic and heightened grief in response to George Floyd’s murder, the Self Maintenance Resource Center was from the start attuned to the power of physical touch and wary of easy methods of meaning-making. “During that time, I was processing so much mentally, it did not make any sense to think about anything in terms of set solutions to the problem. There was so much uncertainty that we had to be open to something that allowed for failure and beautiful curiosity.”

In the place of polished artworks attributed to a singular artist, the SMRC celebrates a vibrant mélange of QTPOC voices — voices that speak to, bounce off of, and expand on each other in unexpected ways. A photo of Naima Green’s lime-green “Unity” sock outside Unity Park in Harlem visually resonates with a series of Pantone swatches a few feet away; in another corner, the lyric score to experimental composer Pauline Oliveros’s “Thirteen Changes” folds over a speaker vibrating with a low beat. Giant enlargements of a “Contract with Mother Earth” vibe with a scholarly piece on the frequency at which music becomes the most meditative. At the time of my visit to the gallery — then featuring Ifekoya, Green, and Rezaire — the theme of self-love mingled with both romantic love and love of the planet.

As should be expected, such love isn’t an orderly affair — nor is it meant to be presented that way. “It’s like the problems around the concept of diversity and inclusion: once it’s packaged up in this bow, it’s not understanding that this process is going to be really messy,” Reynolds explained. “Self Maintenance Resource Center is messy — not just because papers are on the floor, but because when you physicalize something that was online, it’s a lot of labor on the institution. It’s very maximalist, rather than the [white cube] minimalism that everybody finds so aesthetically pleasing.”

Perhaps the most cogent moment for me was coming upon Tabita Rezaire’s video depicting the tip of a single finger of a Black person slowly approaching a green-and-yellow caterpillar moving across a branch. How long had I been exposed to white hands, white faces, and white voices elucidating nature? That something so undeniably normal as a Black finger pointing seemed surprising was a jolt to the senses, a new awareness of how myriad forms of media condition audiences to see knowledge and empiricism as white domains, when they are anything but.

The exhibition divides the viewer’s attentions between the materials on the floor and the walls, and sound coming through strategically placed subwoofers. “There’s a need right now for frottage — that rubbing up against that we need to survive,” Reynolds asserted. “I want Self Maintenance Resource Center to present a non-dramatic and raw relationship with intimacy — to lean into that friction.”

At a time when proximity to other humans has come to feel irresponsible, the SMRC considers how primal physical intimacy is to both human understanding and QTPOC normalcy. “A lot of what I hope for is not a bells-and-whistles utopian vision,” said Duplan, “but a normal existence for QTPOC. What’s normal now is white supremacy, so the mundane is also related to white supremacy. Grief is the way in, but the place we land is more about living and touching — to, in futurist terms, leap past the spectacular back into the regular.”

From the vantage of a white, femme, straight-presenting lady-critic, Self Maintenance Resource Center compelled me to reconsider the endless ways in which my daily intimacies remain gloriously banal — from subway smooches to terrier-tending to sweaty post-jog hand-holding. Shouldn’t everyone have access to the private in this way? Shouldn’t QTPOC people get to bask in the brazen mundaneness that I take for granted?

“I’m not sure how you can talk about love without being personal,” Reynold reflected midway through our tour of the gallery archive. After seeing, hearing, and contemplating the many voices of the space, it’s a little bit clearer how the artistic process itself is inherently vulnerable, how “self-maintenance” is never a discrete, individual process, no matter the “self-love” marketing ploys of our intensely neoliberal era. Self-maintenance, and the small and mighty liberties it always and already affords, only can be possible through ebullient collaboration — a willingness to rub up against, canoodle, converse, and create.

Self Maintenance Resource Center continues at The Luminary (2701 Cherokee Street, St. Louis, Missouri) through July 24 and can be accessed digitally thereafter.

0 Commentaires