In the early 20th century, at the height of the silk manufacturing boom in the United States, hundreds of Armenian and Syrian weavers migrated to the town of Summit, New Jersey, to work in its mills. When artist Bryan Zanisnik began researching the city for a Summit Public Art commission, he decided to create a monument that would both honor this “forgotten history” and unearth its archives for current residents to appreciate.

“These workers who came from [historical] Armenia and Syria really built this town and contributed so much, but very few people know about their histories today,” Zanisnik told Hyperallergic, adding that Summit was second only to the neighboring town of Paterson, America’s “silk city,” in producing the fiber. “This is a monument to these people, to their ancestors, to the grandchildren of these immigrants.”

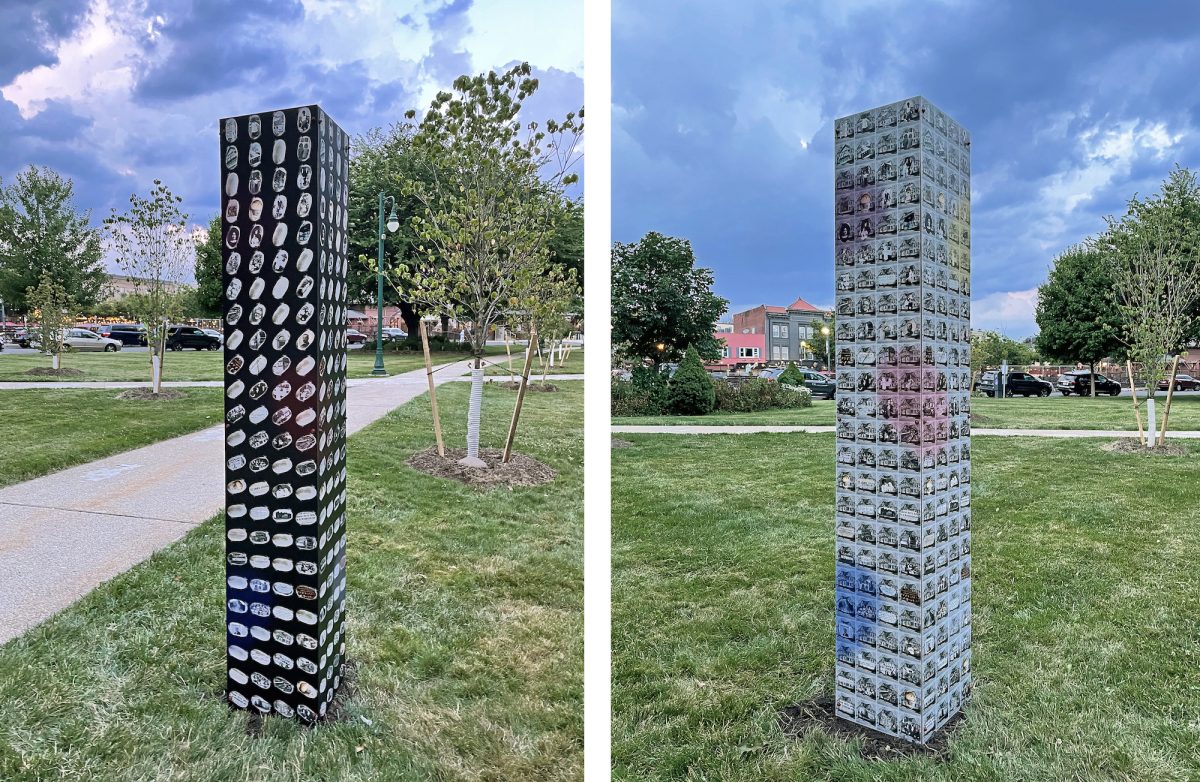

His “Silk Monument” (2021), consisting of two columns covered in archival images printed on aluminum dibond, has just been unveiled in Summit Village Green Park. One of the sculptures features edited photographs of Summit’s Neighborhood House, a community center that served the immigrant labor force from the silk mills as well as their children and families. The second column is overlaid with images, texts, and other records that Zanisnik culled from the depths of Summit’s historical archives, online sources, and conversations with locals. On close inspection, each of the photos — portraits of weavers and their relatives, their homes and places of work — is framed in an oval pod imitating the cocoons of silkworms, from which silk threads are unraveled.

“I was thinking about the viewer’s relationship to these sculptures, and how from a distance, they look very formal, but as you get closer, there are all these details about the Syrian-Armenian community and historical architecture that begins to reveal itself,” Zanisnik said.

The artist’s tribute comes just two months after President Joe Biden officially recognized the Armenian genocide, calling the killing and displacement of 1.5 million Armenians by the Ottoman Turks in 1915 a “campaign of extermination.” With this statement, the United States joined the 30 countries that have formally recognized the genocide, after over a century of evasive terminology used by US presidents who feared alienating Turkey, the Ottoman Empire’s modern-day successor.

Syria and Armenia have a long relationship of mutual aid. During the genocide, Syria took in refugees from Armenia, survivors of the death marches and mass displacement campaigns. In the last decade, Armenia has opened its borders to Syrian refugees, welcoming around 22,000 Syrians who fled the ongoing civil war. In its acknowledgment of the Syrian and Armenian diasporic community, Zanisnik’s public artwork also recognizes the deep-seated connection between the two countries and their shared traditions of silk weaving.

Though the arrival of migrant weavers to New Jersey predated the Meds Yeghern (the term Armenians often use to describe the genocide), Zanisnik said Biden’s announcement was on his mind while completing the sculptures. “It was so long overdue,” he said. “It gave my work another layer of meaning.”

0 Commentaires