It’s one thing for art of the AIDS crisis to be the subject of a thematic museum exhibition, but what happens when AIDS enters a blue-chip gallery? This summer and fall, David Zwirner is organizing a series of exhibitions under the title MORE LIFE, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the Center for Disease Control’s first published report officially acknowledging the epidemic. The decision to mark this date has triggered many conflicting feelings from the queer community, given its inaccurate acknowledgment of when the crisis actually began in this country. In reality, people were dying of AIDS-related complications throughout the 1970s. However, as it ravaged marginalized communities whose deaths were easily attached to other causes (“junkie pneumonia,” for example), the medical establishment was slow to flag what would turn into a full-blown epidemic. Even after the CDC published their report in 1981, AIDS only became a topic of mainstream debate when the famous actor Rock Hudson tested positive in 1985, the same year that President Reagan (another actor) first publicly mentioned AIDS.

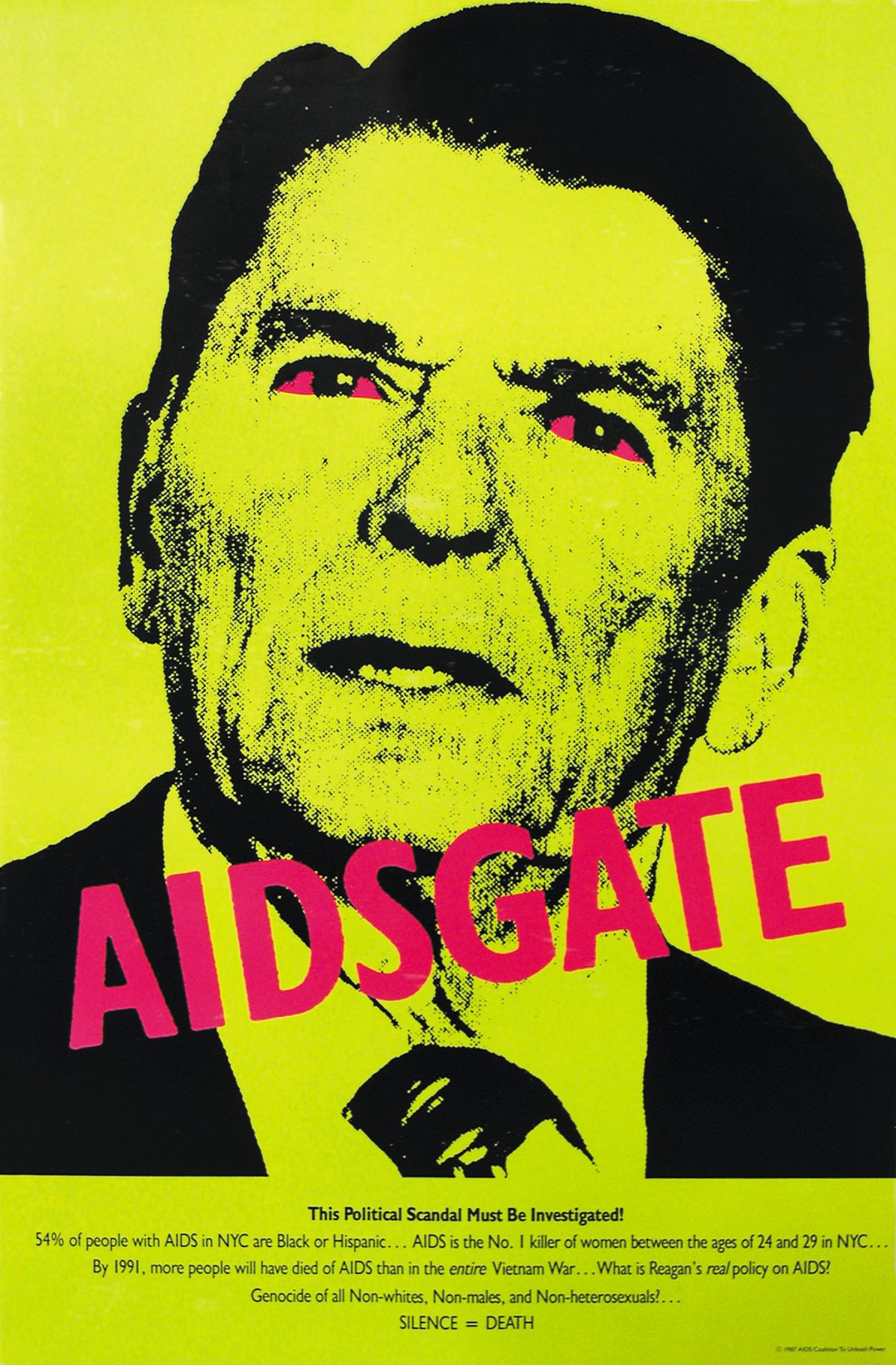

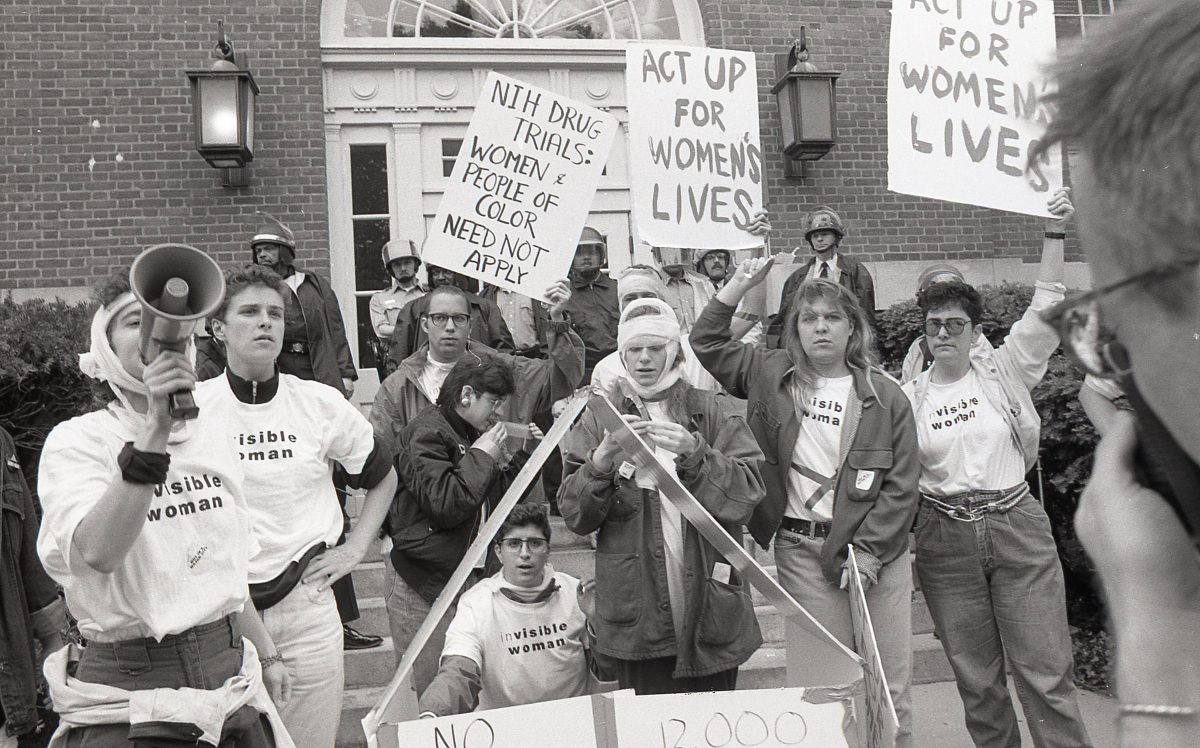

Thirty-six years later, the AIDS crisis has become periodized as a movement in art history, and the last two decades in particular have witnessed an increased interest in artists associated with the epidemic. From a total of eight artists that David Zwirner will highlight, the work of three are currently on view at their 19th street location: Derek Jarman, Marlon Riggs, and the Silence=Death collective. The latter is the only collective included in this endeavor, the remaining seven artists all being individual gay men who died of AIDS-related complications. Starting with the Silence=Death presentation upon entrance, the gallery offers a visual narrative centered around the creation of the collective’s iconic poster in 1986, which has become emblematic of the AIDS crisis. Several vitrines showcase AIDS activism ephemera, photographic documentation of protests, and miscellaneous agitprop — materials that demonstrate that the epidemic was as much a sociopolitical crisis as it was a health crisis.

The majority of these materials were sourced from Avram Finkelstein’s archive, one of the original founders of the Silence=Death collective and Gran Fury, who has also curated the magnificent exhibition OMNISCIENT that opened at the Leslie Lohman Museum last week. Tellingly, this is also the only part of More Life that includes lesbians, featuring photographs by Lola Flash and Donna Binder, as well as a stack of the signature “If they were still alive today…” posters by fierce pussy, a lesbian activist artist collective formed in 1991, committed to advocating for lesbian visibility during the epidemic.

One of the vitrines includes my friend LJ Roberts’s personal “Read My Lips” t-shirt. When we visited the opening together, I asked them how they felt about it. “The weird part of the t-shirt is that I almost never show my own work commercially,” LJ responded, “Not by choice, but because commercial galleries aren’t interested. But they were psyched about a stinky t-shirt.”

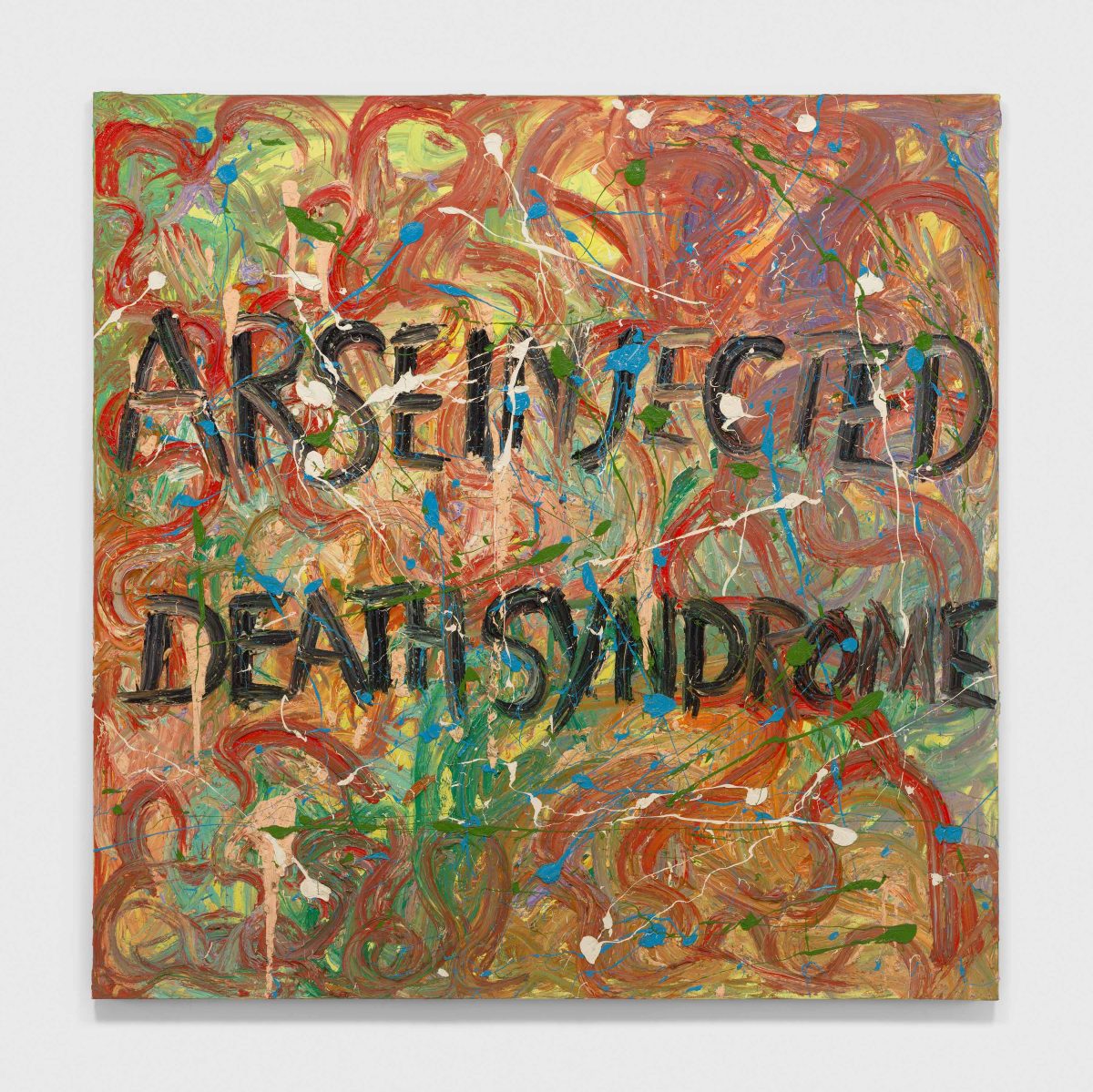

Spread across three walls, Derek Jarman’s Evil Queen series (1992–93) beckons the viewer into the subsequent galleries. These colorful, highly emotive paintings are executed with thick, heavy brushstrokes that reveal the passionate rage and raging passion imbued in each movement. Written into the painted surface are short phrases such as “AIDS Isle,” “Sexboy Sale,” and “ACT UP.” I can picture these works at Jarman’s seaside cottage in Dungeness, where he retreated after his 1986 HIV diagnosis. He spent much of his time creating a magnificent garden (a process he documented in a diary, now published as the book Modern Nature), the lushness of which is reflected in the paintings.

Yet, while David Zwirner showcases some photographs of Jarman’s cottage and garden, captured by the British photographer Howard Sooley, the paintings appear cold, lifeless, and out of context on the white gallery walls. This is where the title More Life — plucked from Angels in America fails for me. Being the bad art historian that I am, I want to rip the paintings off the wall and take them to East River Park to watch the sunset with me (accompanied by a conservator, of course).

Still, the exhibition continues with another piece by Jarman, a grey curtain leading into his most celebrated film Blue (1993). A monochromatic screen radiating Yves Klein Blue (Jarman experienced a temporary blindness that caused flashes of blue to sporadically appear in his eyes) is overlaid with several voices, including the artist’s own, reading a poetic meditation on illness, mortality, and the AIDS crisis. The work certainly holds its own at Zwirner; soaked up by the blue, you forget where you are.

The same is true for Marlon Riggs’s iconic documentary Tongues Untied (1989), which can be viewed in a separate space a few doors down, on the largest screen I’ve ever seen it. The piece is an essayistic montage of poetic monologues and testimonies by Black gay men, including the poet Essex Hemphill and Riggs himself, skillfully interwoven with archival footage capturing scenes of performance and protest. Giving voice to his community while also re-enacting the violent hate speech directed at them, Riggs exposes the deep wounds of homophobia and racism in our society, all the while urging that “Black men loving Black men is the revolutionary act.”

I have to credit David Zwirner for the many ways in which they have included the queer community in More Life. Sterile environs aside, many of the shows in the series are curated by people who personally knew the artists, and additional programming has included panels with queer icons such as Gregg Bordowitz, Sarah Schulman, and Pamela Sneed — as well as Finkelstein. Wisely, the gallery also features an alternative AIDS timeline on their website, created by the collective What Would an HIV Doula Do (who have launched an AIDS IS / AIDS AIN’T 40 campaign, the name itself a reference to Black Is / Black Ain’t, a 1995 film paying homage to Riggs).

Still, I can’t help but have mixed feelings about the whole initiative. Having only lasted fifteen minutes at the opening night, I sat down for strawberry lemonades under a strawberry full moon to meditate on the experience with friends — all queer artists. We went in expecting to see the usual queer art crowd, and instead stumbled into a sea of haughty art people. I even caught a glimpse of a wealthy art collector I once knew in a different lifetime, who never showed any interest in my dissertation topic on art, AIDS, and lesbian identity. Yet here she was, all dressed up for the Zwirner opening.

Despite the good intentions, careful attention to language, and inclusion of the queer community, I worry about the continued commodification of queer culture — a Derek Jarman painting becomes an expensive object on the wall of an extravagant beach house in the Hamptons, its power as an index of rage contained by the sleek walls. Here and elsewhere, art of the AIDS crisis is still presented as being defined by gay men, leaving little room to consider the myriad of other ways that artists — lesbians and trans people in particular — were affected, and shedding insufficient light on the emotional trauma, survivor’s guilt, and many additional deaths not directly caused by HIV infection that were still very much AIDS-related.

The first four exhibitions of More Life (Derek Jarman, Mark Morrisoe, Marlon Riggs, and Silence=Death) continue at David Zwirner (multiple locations, Manhattan) through August 3. Further exhibitions will open starting September 14.

0 Commentaires