ROME — Standing in front of a huge, darkly glittering wall mosaic from the first years of the third century CE, I find myself drawn into a lost world. A ship is departing a port in Alexandria, Egypt, its sails billowing, sailors working the ropes, and to the left is a tall lighthouse. This window into the Roman empire comes from the domus (or mansion) of Claudius Claudianus, a senator of African origin, who made his money in Mediterranean transport. It’s not hard to imagine that what I’m looking at is one of the many grain ships that provisioned ancient Rome from the Nile valley.

Colori dei Romani: I mosaici dalle Collezioni Capitoline (Colors of the Romans: Mosaics from the Capitoline Collections), an exhibition now on view at the Montemartini Power Station display space, just south of central Rome, has thrown open many windows like this for visitors. Curated by Claudio Parisi Presicce, Nadia Agnoli, and Serena Guglielmi, the exhibition is separated into four sections: the first explores the history and development of the mosaic form in Roman art; the second puts mosaics, frescoes, statues and artifacts together to create a sense of what it was like to live in luxurious residences of the empire’s ruling class; the third gives an example of how mosaics were used in religious buildings and sacred spaces; and the final section, a tiny coda, looks at tomb mosaics.

For an exhibition put together at the height of the pandemic, and with the restrictions inherent in a display that is limited to artifacts already in the city’s possession, it’s a triumph, with judiciously-chosen pieces excellently displayed and labelled. English-speaking visitors will be pleased to find that every piece of curatorial text in Colori dei Romani is in both Italian and English, though unfortunately the small catalogue is only available in Italian and lacks a detailed description of each piece.

We have lost so much from the civilization of ancient Rome, a loss whose extent is hard to conceive. And despite several decades of effort to the contrary, the general public’s idea of the ancient city is one of gleaming marble buildings, a formal backdrop for the drama of Roman history with its murders and betrayals. Film has a lot to do with our idea of what ancient Rome looked like, and most films about the city show it as vast, monumental, and white, filled with pale-skinned people. But the empire was multiracial, multicultural, polytheistic, and polyglot, and its capital certainly reflected this.

As Sarah Bond has written for this site, we have been taught to look at the ancient world in white, and we have to relearn it in color, as ancient people themselves showed it.

This persistent whiteness of our imaginary Rome is precisely why this exhibition is such a worthwhile corrective. Presenting pieces from the city’s vast collections, the exhibition gives us a dazzling glimpse into the colors of ancient Rome by focusing on the only technique whose color doesn’t fade over time, the mosaic. The addition of other objects like statues and frescoes from the same archaeological sites, where possible, helps evoke the environments of a selection of Roman buildings.

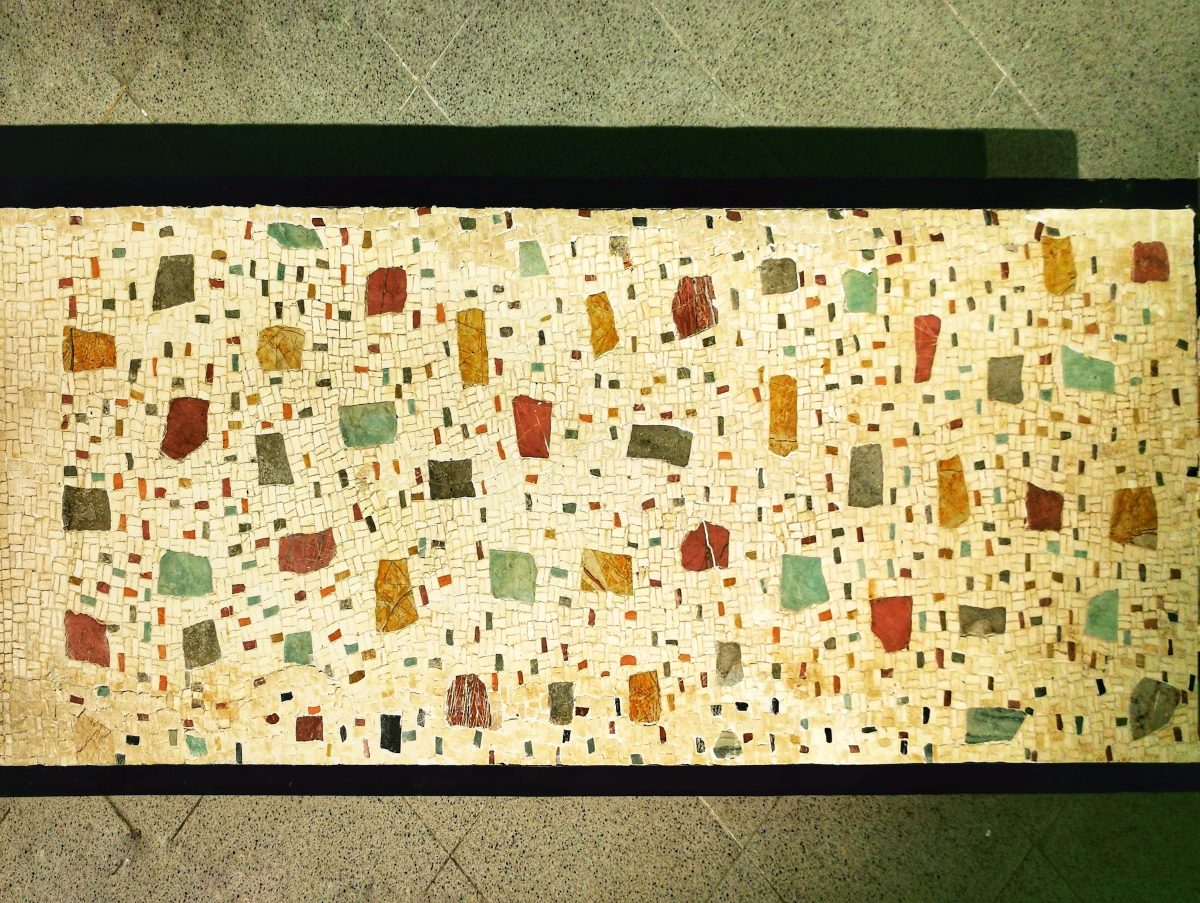

Mosaics were closely connected to paintings right from the start. The ancient Roman writer Pliny the Elder (c. 24–79 CE) ascribed the invention of mosaics to the Greeks: “pavements began with the Greeks, and were decorated with art analogous to painting.” Floor mosaics, smooth and made with small flat tiles, were probably first introduced as a decoration in the city’s principal temple, that of Capitoline Jupiter, in the mid-second century BCE, but only really began to spread in Rome itself in the first century BCE. The first mosaics were simple white stone tiles with multicolored inserts, known as “woven work” because the tiles were set in pairs in alternating directions. The result was decorative but a little crude. At the same time, black and white mosaics with geometric patterns began to be used in wealthy homes and the skills required to make mosaics quickly became specialized. With Rome’s colonial expansion across the Mediterranean, the empire’s access to both wealth and more skilled artisans produced mosaics of ever-improving quality

It was possible for the ancient Romans to import a micromosaic rectangle from Greece, known as an emblema, which might reproduce a famous painting but in any case would have a detailed scene on it using mosaic tiles or tesserae, sometimes no larger than two millimetres wide. This is the “art analogous to painting” referred to by Pliny. The emblema, not very large, would be set into the middle of a floor of simpler mosaic made by local craftsmen in Rome. While I would have liked to see more early mosaics, this exhibition features some beautiful emblemata, including a series of underwater scenes as well as episodes from myths. The Romans, not content with leaving mosaics on the floors, put them on the walls and in their garden fountains, often using iridescent shells and, from around the middle of the first century BCE, also glass tesserae, which caught and reflected light better than stone. The exhibition shows how Roman craftsmen worked in synthesis with artisans from across the empire, and how, by divorcing mosaic work from an exclusive role as pavement decoration, they literally elevated the mosaic into a major art form. A glance at any of the late imperial buildings in Ravenna, which glitter with wall mosaics, shows us how important this development was. In this context, it is particularly thrilling to see pieces taken from warehouses and even out of city buildings where they were ignored and inaccessible, and shown to the public.

Colori dei Romani covers the chronological development of mosaics, displaying examples of the heightened skill of Roman craftsmen and changing tastes over the centuries, most of which have not been seen publicly for decades. One of its most successful feats is the reconstruction of the interior decoration of an ancient Roman house from the mid-first century CE, which was excavated from underneath a fire station on Via Genova. The owner of this house, Titus Flavius Salinator, can be identified from the inscription of his name on its lead pipes. Here we have not just the floor mosaics but the wall frescoes and a selection of the statues found on the site, as well as one of the lead pipes. In an adjacent section of the exhibition, the residence of the aforementioned Claudianus, from around the year 200 CE, likewise yields incredibly rich mosaic decoration.

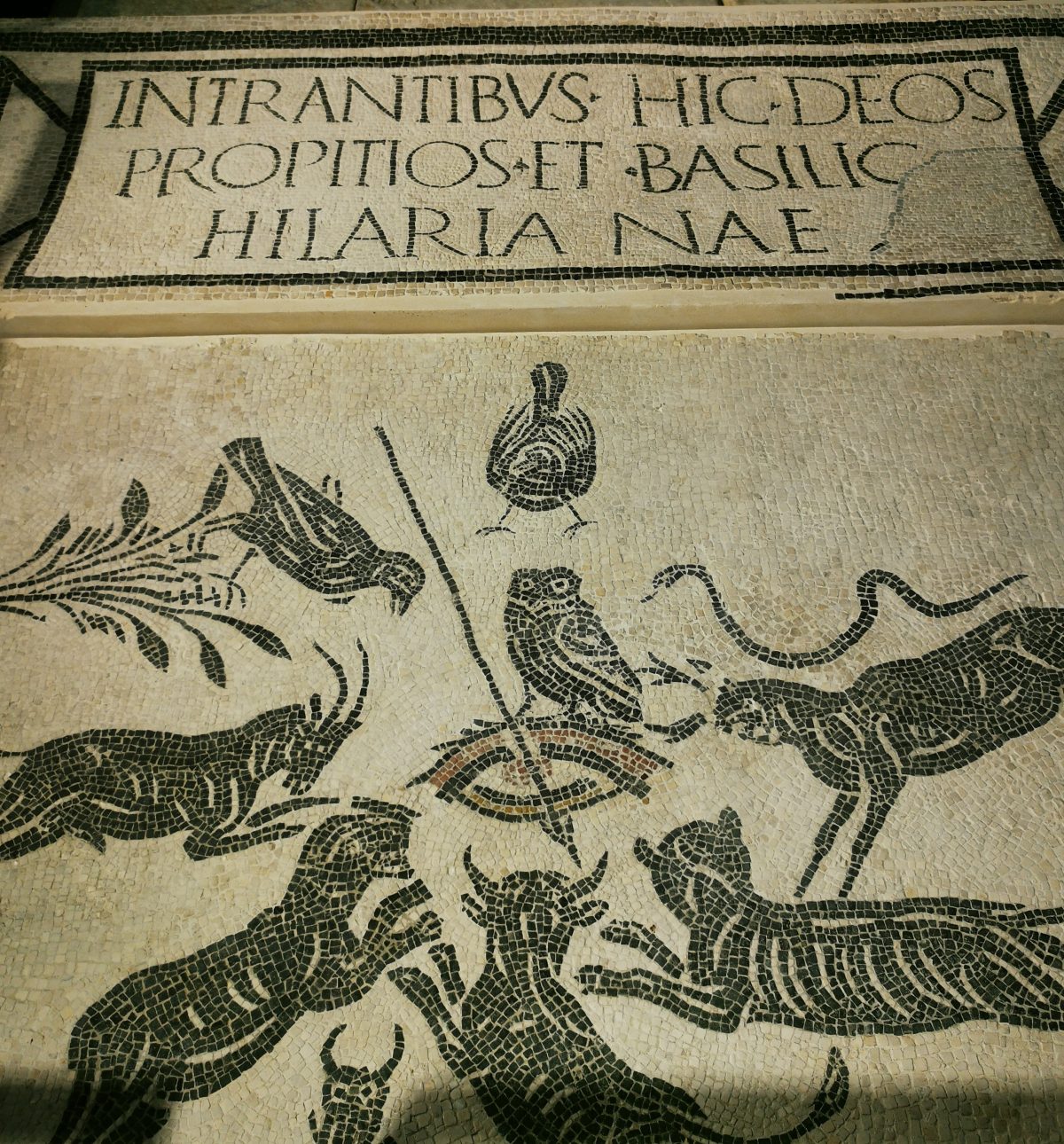

The exhibition’s subsequent section moves into the religious life of ancient Rome. Here the highlights are mosaics from a religious building complex, the Basilica Hilariana. The seat of a priestly college dedicated to the gods Cybele and Attis, a cult from Asia Minor, its floor mosaic is one of the most fascinating, depicting various forms of attack directed towards an evil eye. The reconstruction of this building’s decoration includes the welcoming mosaic inscription “To those who enter here and to the Basilica Hilariana, may the gods be propitious.” The sponsor of this hall, Manlius Poblicius Hilarus, named the basilica after himself and included his portrait bust and a long self-praising inscription. This is a small example of a big phenomenon: Even in ancient Rome, sponsorship of sacred sites was not just a spiritual responsibility but also an important act of self-promotion.

The exhibition closes with some examples of funerary mosaics, including a magnificent octagon containing two multicolored peacocks and poppies, from the floor of a family tomb. What is impressed upon the visitor is the spectacular variety of mosaic styles, some naturalistic — some almost Art Deco — that filled Rome and its empire not with white marble temples but shimmering, joyous color.

Colori dei Romani: I Mosaici dalle Collezioni Capitoline (Colors of the Romans: Mosaics from the Capitoline Collections) continues through September 15 at Centrale Montemartini (Via Ostiense 106, Rome, Italy). The exhibition was curated by Claudio Parisi Presicce, Nadia Agnoli, and Serena Guglielmi.

0 Commentaires