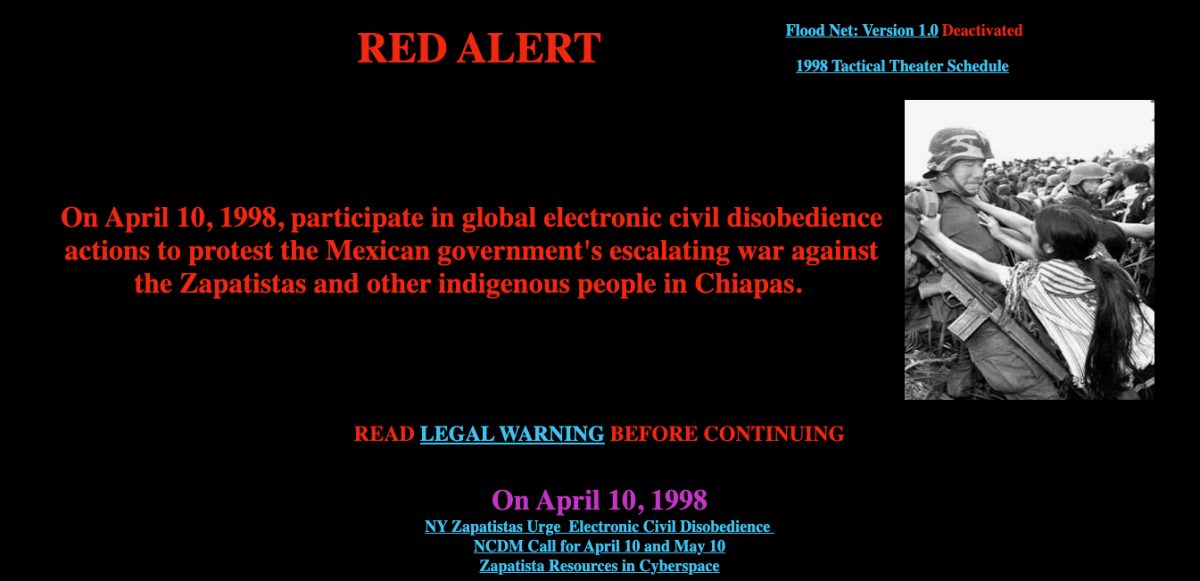

On April 10, 1998, the website of Mexico’s then-president Ernesto Zedillo slowed down, crashing intermittently. It was the anniversary of Emilio Zapata’s death, and people in 23 countries were taking part in Electronic Disturbance Theater’s act of electronic civil disobedience in solidarity with the Zapatistas. Their “FloodNet” applet allowed participants to input “requests,” for truth, justice, or freedom. Participants received an error code, 404 justice not found, while these requests piled up in the website’s server logs. This was just the dress rehearsal; EDT would perform nine acts of “FloodNet” in that year as the protest form began to grow.

I first encountered electronic civil disobedience when researching a later project by EDT. My journey into the topic was littered with broken links, 404 pages, static screen grabs. I wondered why these works of net-based protest art had been largely forgotten, and whether there was any merit in dusting them off today.

Developed by Critical Art Ensemble in their 1996 text, electronic civil disobedience sprung from conceptions of the streets as “dead capital.” Power had become increasingly dispersed and liquid, and so resistance should be too. Cyberspace was to be the primary site of struggle. Belief in this increased. Two years later, EDT member Stefan Wray claimed definitively the coming century would see the emergence of electronic civil disobedience as a genuine mode of protest. And, for a while, it was, and not just on a small scale. While CAE believed it should be an “underground activity,” practitioners turned it into a public spectacle, actively engaging large numbers of “ordinary” participants. EDT’s “SWARM the Minutemen” (2005), had allegedly over 75,000 participants throughout its two-day duration, and Electrohippies claim to have attracted 400,000 to their 1999 action against the World Trade Organization.

But from the mid-2000s, engagement with the form declined. This is unsurprising: so much of the language, the ideas, the justification for the form was contingent on conceptions of the internet that now seem outdated. In 2019, I interviewed artist Ian Alan Paul, whose 2011 work “Border Haunt” staged a “symbolic haunting” of the United States/Mexico border. He too argued that the politics on which electronic civil disobedience rested had “largely been abandoned” and now treated with “skepticism and suspicion” at best.

Central to these politics was the idealistic differentiation between cyberspace and physical space. While physical space lagged, cyberspace presented open planes of opportunity, to be shaped as the agitator saw fit. In contrast to physical space in the US, which EDT front-man Ricardo Dominguez described as almost entirely privatized, Dominguez argued the internet could “still serve as a commons” for people to create social change. It’s a compelling idea, and one that makes clear why this move to net-based protest felt so urgent. In 2021, this seems idealistic. Mainstream use of the internet is now largely controlled by a small number of corporations. Cyberspace has been privatised too.

More broadly, electronic civil disobedience was built on the assumed empowering potential of the internet not just as a “commons.” Advocates for the equalizing power of cyberspace often subscribed to a dream that the internet allowed identities like race, gender, class, and nationality to be ‘left behind’. But ignoring these identities let the offline structures that shaped them replicate in cyberspace. This criticism is perhaps less obvious when it comes to electronic civil disobedience; after all, these performances were often constructed in solidarity with minoritized groups. As works that relied on the mass participation of individuals, practitioners employed this same universalising approach, that everyone had equal potential to participate, all connected through the borderless terrain of cyberspace. Communications scholar Fidele Vlavo went as far as to question whether these “visions of so-called transnational solidarity and global mobilisation” actually minimized the distinct struggles of affected groups or populations.

Is, then, there any future left for electronic civil disobedience? While I am skeptical of the merit of rehashing the form verbatim in an almost alien context to that in which it arose, I don’t think it’s time to close the door altogether. As recent years have seen increasing levels of online activism that amount to expressions of visibility politics, now is an ideal time to consider how we can use the internet within resistance. When speaking to Paul, he argued that “resistance, by its very nature, is always speculative” — the outcome, the impact is never known before you embark. I often think of the language many practitioners of the form used, referring to their performances as “experiments,” or as “gestures.” And while these experiments were often contradictory, perhaps resistance should inhabit contradiction, and should experiment, in search for new ways to disrupt and confront liquid and dispersed power.

0 Commentaires