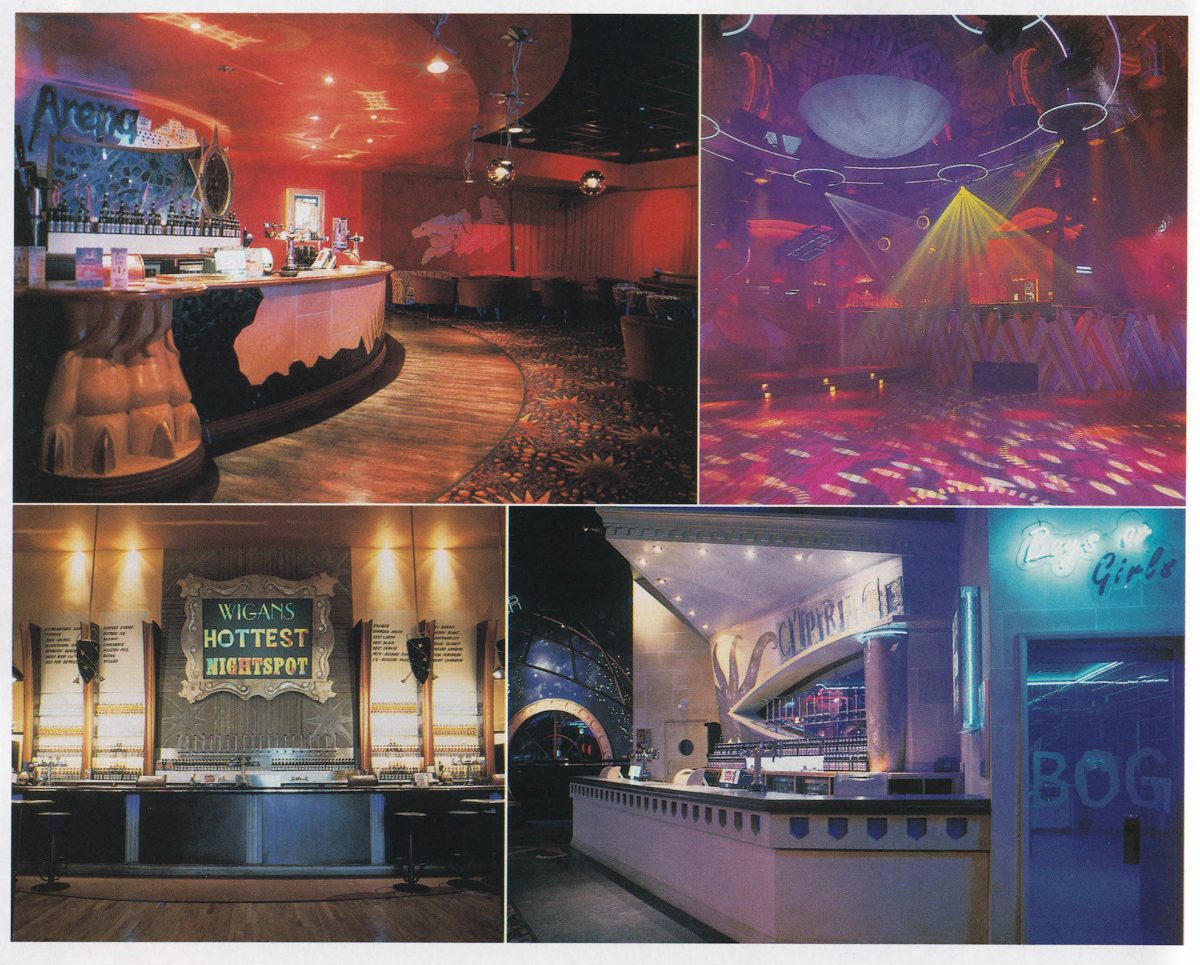

Multicolored laser beams, day-glo dance floors, mirror-plated ceilings, kitschy patterned carpets, giant spaceship sculptures: from its nascence in the 1960s, discotheque aesthetics has been defined by the whimsical and the offbeat. Those familiar with artist Adrian Wilson, better known today for his humorous, subversive interventions across New York City, may be surprised to learn that he got his start reveling in this unique typography, capturing the heyday of European disco design in the late 1980s and ’90s.

As a freelancer for trade publications like Disco Mirror and European Discotheque Review for 11 years, he shot over 800 venues, including Ministry of Sound in London; Ku Club in Ibiza; and Le Malvern in Arzon, France. Using medium format slide film, Wilson says, he “documented the golden age of discos before bottle service and bland design.”

“After I stopped shooting for them, the magazines threw out all the images,” the artist told Hyperallergic. “I don’t blame them — at the time, I saw no value in 10-year-old random discos either, but now I think these would make an amazing book.”

Because the magazines depended on the advertising dollars of the companies that furnished the spaces or installed equipment, Wilson always photographed the clubs empty. As a result, the images are strikingly crisp, rare views of legendary venues like the 65,000-square-feet Genux club in Rimini, Italy — which featured a massive light fixture in the shape of a human brain suspended above the dance floor and claimed to be the largest disco in the world.

“Suddenly it became a kind of fantasy world where everyone was doing these themed nightclubs with crazy things like viking boats and volcanoes, anything to attract people,” Wilson said.

His favorite disco, however, Club Paradiso in the Northern Italian city of Rimini, was not the most eccentric but rather “supremely elegant.”

“It was the best-designed place in the world,” he continued. “I seem to remember they had cameras pointing at other tables so one could check out the other customers by looking at a TV screen on the table instead of looking at them.”

Seen today, when mass-produced minimalism and mid-century modern monotony continue to dominate the landscape of design, Wilson’s images of the quirky and extravagant disco interiors are immediately enchanting. But that wasn’t always the case, the artist says; when he approached Architectural Review with the photos a few years back, an editor described 1990s disco design as “universally abhorrent.”

“There was a snobbery toward discos,” Wilson said. “Because they weren’t really bound by taste or anything. They were meant to be a fantasy land, escapism. And that’s kind of missing nowadays.”

0 Commentaires