In his brief time as an artist, Matthew Wong (1984–2019) addressed a paradox that haunts artists who work in traditional mediums: how do you accommodate the medium while also becoming yourself. It takes some artists years to become themselves, while others seem to balance traditions and individuality from the outset. Wong belongs to the latter group.

For Wong, an artist of Chinese descent, living and working in Hong Kong, Zhongshan, China, and Edmonton, Canada — the East and the West — the paradox encompasses cultural and racial considerations. I think this is reflected in his first choice of materials, which he continued to use throughout his the rest of his life.

In 2012, shortly after Wong graduated from the City University of Hong Kong School of Creative Media with an MFA in photography, he began drawing. In 2014, in an interview in online magazine Altermodernists (October 29, 2014), he stated that he initially started with a sketchbook and a bottle of ink and making “a mess every day randomly.”

He also stated:

Art is all-encompassing in my daily life. When I’m not working, I’m at the library doing research into the history of art, figuring out where I can fit into the greater dialogue between artists throughout time, or on the internet looking at art-related websites and engaging in dialogue on social media with artists and art-world figures around the world.

Wong had his debut solo show in New York at Karma in 2018. His second show at Karma, Matthew Wong: Blue (November 8, 2019–January 5, 2020), was posthumous. While it was apparent from his first exhibition that drawing was central to his practice, and that he proceeded mark by mark, it was not clear until his current exhibition, Matthew Wong: Footprints in the Wind, Ink Drawings 2013 – 2017, at Cheim & Read (May 5–September 11, 2021), just how deeply his work is rooted in the practice of ink drawing on rice paper.

Rice paper was invented in China at the beginning of the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE). Initially used to write on, it was not until the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368) ruled China that artists who wanted to break away from previous generations began painting in ink on rice paper rather than silk. I cannot imagine that Wong did not know this history. It seems that consciously being a Chinese artist was the foundation upon which he began and from which he never wavered, even as he absorbed a wide range of references and influences. In the catalogue published on the occasion of this exhibition, Dawn Chan writes:

We know that Wong specifically fixed his attention on the art of Shitao, as well as those of his [Shitao’s] contemporary, Bada Shanren. Both artists were famous for pushing the envelope in their work — for moving ink painting towards surprising moments of expressive abstraction. Their influence is deeply integrated in Wong’s own works. Wong maintained a committed ink-art practice, making an ink painting every morning. Painting immediately after waking, before food or coffee, he experimented boldly with the medium, pouring paint and letting it pool on the page.

It seems to me that this should change how we look at Wong. Instead of seeing him as a self-taught Chinese artist gesturing toward the work of western artists, such as Vincent van Gogh, Lois Dodd, and Julian Schnabel for inspiration and guidance, as Roberta Smith and Jerry Saltz proposed, he was absorbing the work of western artists through the lens of Chinese art, specifically ink painting, which cannot be revised or scraped away, as well as carved lacquerware.

Like the older Chinese artist Liu Xiaodong (b. 1963), who has expanded the common view of realism and observational painting by working on site, often on a monumental scale, Wong has broadened what is commonly defined as calligraphic art and painting based on mark making. Liu redefined observational painting in order to subvert the propagandistic idealization of Russian-style Socialist Realism, which he learned in school, while Wong expanded ink painting out of a desire to make a space in which the two cultures that shaped him fit together. For these reasons this exhibition is important to an understanding of Wong’s work. It charts his development as well as underscores his decisiveness and self-directed drive.

Given the misguided view among many westerners of Chinese art as a tradition based on copying, it is not surprising that the New York art world has qualified its recognition of Liu and Wong as innovative artists who moved both western art (realism) and Chinese art (abstract mark making) in a new direction.

In “Untitled” (ink on rice paper, 15 1/2 by 27 inches, 2013), the earliest work in the exhibition, Wong stained the absorbent paper with different densities of ink, ranging from deep black to washy gray, essentially eschewing the calligraphic line. It is, of course, calligraphy that most appealed to western artists interested in line, from van Gogh to Mark Tobey and Robert Motherwell.

By staining the paper with irrevocable shapes and marks, Wong undercut any evidence of tentativeness that he might have felt. What is remarkable about this early ink is the degree of confidence with which Wong evokes a complex, atmospheric space of near and far.

Wong’s process for the ink drawings was incremental. In “Untitled” (ink on paper, 31 by 57 ½ inches, 2014), he poured ink as well as used a loaded and dry brush, depending on what he was after. As with the 2013 work, the subject is an abstract landscape that viewers cannot quite identify. Each mark, series of marks, or shape, seems to have called him to make another in response.

In “Untitled” (ink on paper, 30 ¾ by 57 ¼ inches, 2014), the dense, irregular grid of ragged, crisscrossing bands is made entirely by pouring, with the bands spreading in different areas and intervals. Already in these early works, the viewer should sense Wong’s restlessness and openness; he was not looking for a signature style.

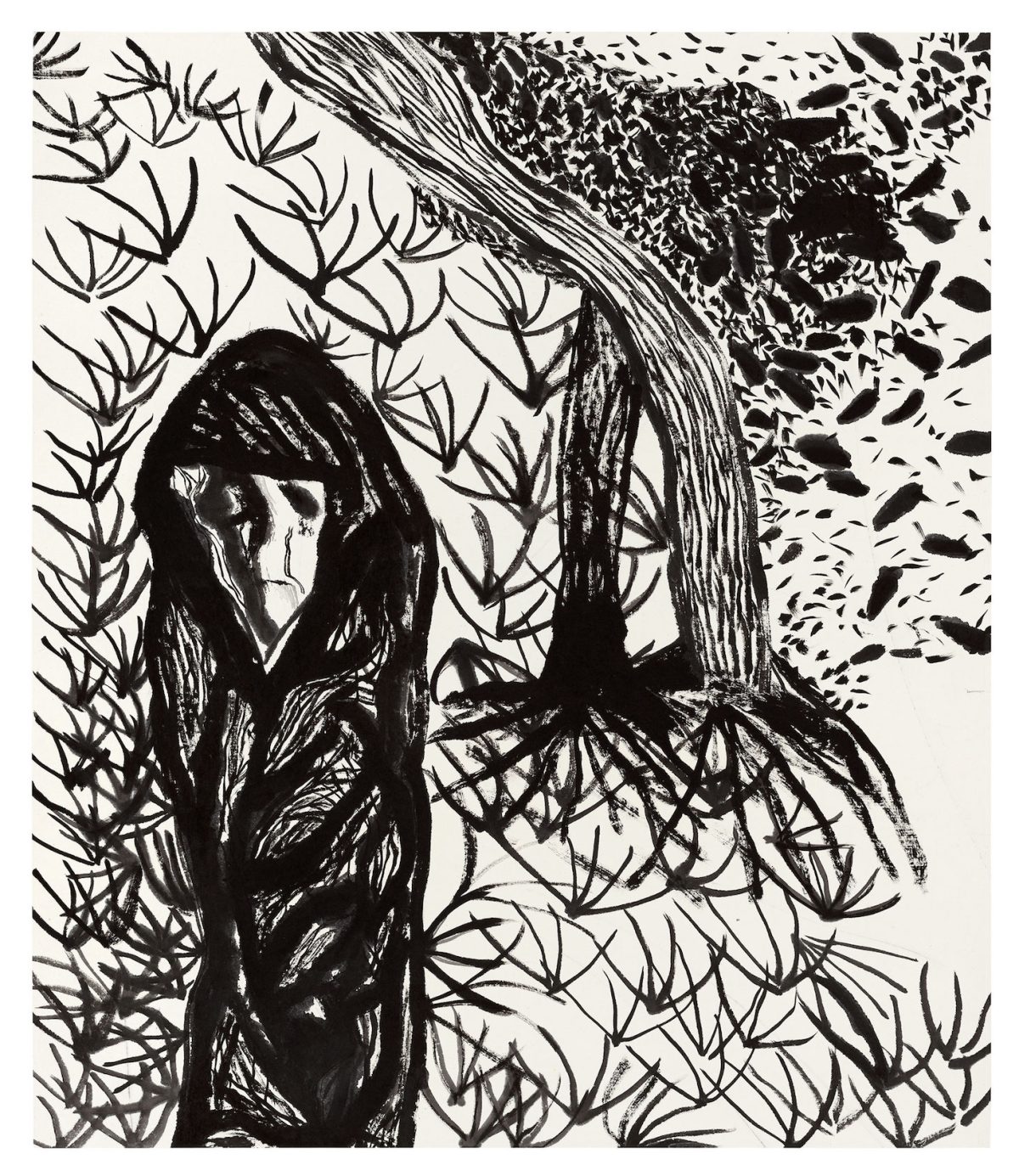

By 2015, he was combining large poured areas with swarms of small, repetitive marks, as in the overtly figurative “Untitled” (ink on paper, 26 3/4 by 22 1/8 inches), which is dominated by a silhouette of a what looks like a young girl that stretches from the paper’s top to bottom edge, amid a welter of vertical and horizontal marks of varying lengths and widths. A large, triangular opening in the silhouette’s rounded face is filled with lines, bonding her to the surroundings. The opening is echoed by another triangle that defines the space separating the nape of her neck, a braid of hair, and her shoulder. A thick brushstroke curving gently down from the front of the girl’s neck to the drawing’s bottom edge accentuates her connection with the surroundings, as the space between the brushstroke and her chest is filled with lines that are similar to those outside the thick line.

2015 also marks the first time Wong titled a work. In the vertical “A Poet’s World” the silhouette of an outlined head and solidly stained body encounter a largely black, abstract landscape in the foreground. The dark landscape at the bottom edge transitions in the middle to outlined leaves and a pattern of parallel lines set at different angles. Above and beyond the figure and foreground, Wong has made a series of vertical lines, with a variety of marks in between. In the upper part of a tree trunk near the left edge, he has written the work’s title ideogrammatically.

It seems to me that Wong strongly identified with the Southern School of Chinese painters working in ink wash. Also known as the literati painters, they were more interested in inner realities than the outward appearances and devotion to realistic detail favored by artists associated with the Northern School. It is best to look at Wong’s art from this perspective.

Remarkable as this might seem, it strikes me that by 2015 — just three years after he first devoted himself to art and drawing in ink — he had found his subject and assembled an abstract vocabulary of pouring, staining, and linework to create an entire world that is parallel to ours.

One of the recurring subjects of the literati painters was a lone traveler observing nature. This became a motif in Wong’s concentrated views of the inside of a flower or a figure gazing at the stars. At times, as in “Winter Wind” (2016), the hooded figure exudes a melancholia that brings to mind the work of Edvard Munch.

In “Odyssey” (2017), a path ascends slowly as it recedes into distance, curving behind a dense archway of black tree trunks. Turning into the darkness, it is hard not to read this drawing metaphorically.

Matthew Wong: Footprints in the Wind, Ink Drawings 2013 – 2017 continues at Cheim & Read (547 West 25th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through September 11.

0 Commentaires