The current humanitarian crisis in Palestine — an indiscriminate bombing campaign in Gaza, continued evictions in Jerusalem, and more, all carried out with contemptuous impunity on an already brutally subjugated population — poses a number of urgent problems, least importantly one of conscience for secular liberal anglosphere Jews such as myself. The asymmetries of power in the Israel-Palestine conflict are so vast, the suffering of the Palestinian people so profound, as to be obvious to everyone with whom we usually see eye-to-eye on questions of justice and anti-colonialism. But for some it’s hard — like, emotionally — to endorse the most virulent condemnations of the Jewish state, given Israel’s place in the story of our faith and culture, as well as our nagging awareness of the prevailing fact of anti-Semitism. Not all of us are handling this well, and I can’t entirely blame them for it. The shift in Jewish identity — or in our understanding of it — from oppressed to oppressor has been swift, absolute, and incredibly disjunctive.

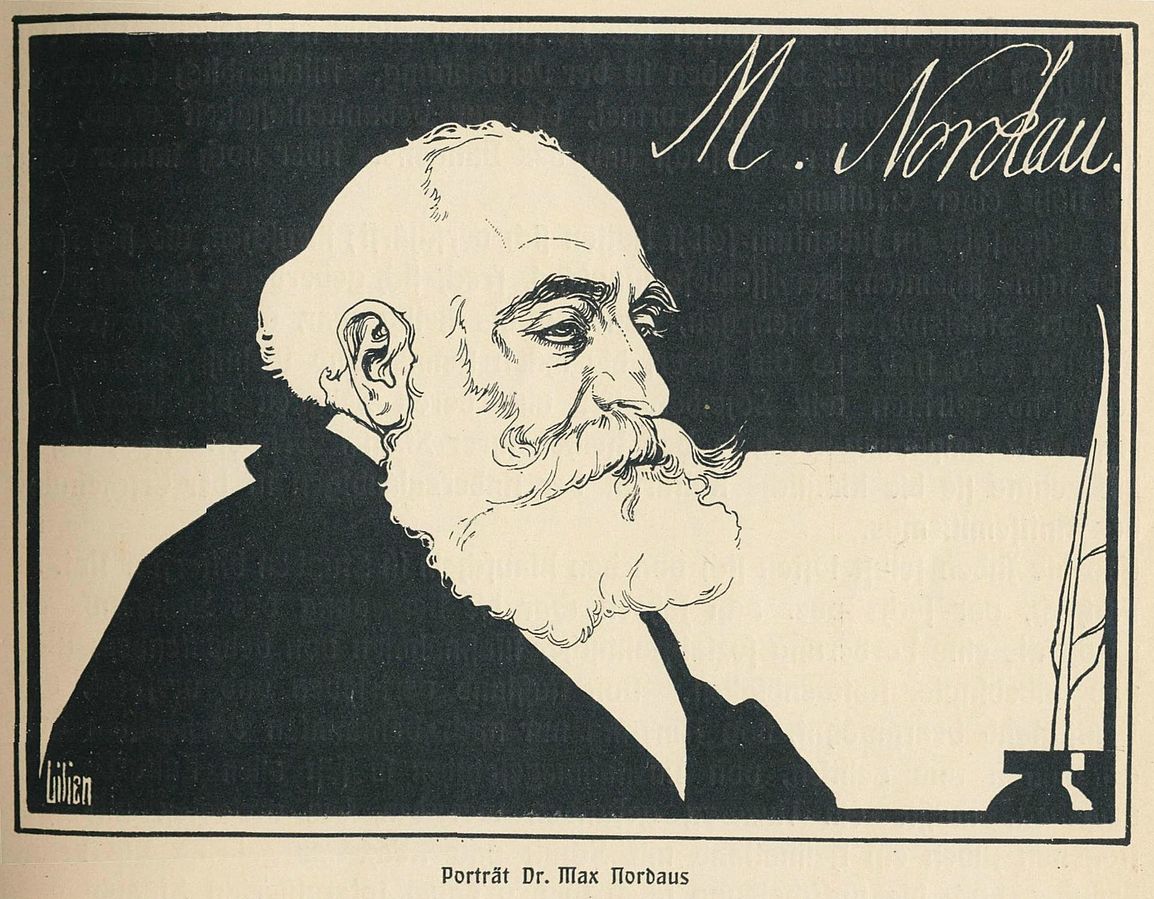

One stage where this identity crisis has played out is Hollywood, where images of Jews as victims and victimizers have often wrestled to a stalemate. In particular, I’m thinking of a cycle of films on the subject of retributive Jewish violence during the Holocaust and through its aftershocks in the Arab-Israeli conflict — films in which narratives of Jewish suffering are enclosed within demonstrations of Jewish power and righteous violence. Troubled fantasies of Jewish state (and deep state) power, they depict, mirror, and question the emergence of the Mossad as modern-day Maccabees in Israeli and American imagination, the heirs to the “Muscular Judaism” articulated by Max Nordau in 1898, with his dream of a stateless, scholarly, soft-hearted people becoming embodied through physical strength in a willful and perhaps aggressive act of self-refashioning and nation-building. These post-traumatic narratives use as figures of identification not passive, helpless dependents of remote terrors, but triumphant, macho agents of history. Continuing the narrative of Jewish identity redirected by Zionists, these films struggle to varying degrees to criticize rather than simply evoke the thin-skinned, hard-bodied mindset of modern-day Israeli society. In so doing, they parallel an American Jewish culture similarly struggling to know its own strength. To quote Daniel Craig in Munich, “Don’t fuck with the Jews.”

In his speech at 1898’s Second Zionist Congress, Nordau introduced the idea of a “muscular Judaism” with the power to “rejuvenat[e]” his people both “corporeally” and nationally. Driven to and fro and into the ghettos of growing European cities by various expulsions and pogroms, the Jewish people — stereotypically weak, brainy, cosmopolitan, more at home with the abstraction of commerce than the concreteness of labor — could overcome their persecution by rebuilding themselves physically as well as politically. (To be stateless meant to be both landless and disembodied, hence the kibbutz movement as an early outgrowth of Zionism, and its emphasis on strenuous agricultural work as the necessary prerequisite for the rebirth of a nation.) As Todd Samuel Presner explains in Muscular Judaism: The Jewish Body and the Politics of Regeneration, Nordau’s ideal had its origins in fin de siècle gymnasium culture and nationalism. The perceived need for a “new, militant and decidedly masculinist Jewish identity” was legitimized by the Holocaust and then affirmed as Israel’s military victories from the 1940s through the ’70s won hearts and minds abroad.

Wth the Eichmann trial, Marc Ellis writes in Beyond Innocence & Redemption: Confronting the Holocaust and Israeli Power, “Jews articulated for the first time both the extent of Jewish suffering during the Holocaust and the significance of Jewish empowerment in Israel.” This is the “innocence” and “redemption” of his title, and the basis of the question he poses: “Are we after our difficult history in Europe becoming a warrior people? Is it possible that the yearnings for a haven from persecution, paid for so dearly in the past, will justify the expulsion and dispersion of another people?” The inescapable image here, in this juxtaposition of moral viability (vouchsafed through suffering) and new muscular vitality (and its latent harmful potential), is something like Angelo Siciliano, the Italian immigrant and 97-pound weakling into whose face the bullies of Coney Island used to kick sand before he transformed into the bodybuilder Charles Atlas, forever flexing and preening.

In film, characters like Eric Bana’s terrorist-tracking Mossad hitman in Munich (2005) or the Jewish-American Nazi-hunters of Inglourious Basterds (2009) are something like modern-day incarnations of the Golem of Prague — earthy defenders of the faith vivified with the hopes and fears of an imperiled people. It bears observation that there’s also a heavy dose of Hollywood wish fulfillment, in that these Golems look not like clay hulks but instead the IDF hotties who chaperone Birthright trips (or play Wonder Woman). In The Debt, a 2010 remake of the 2007 Israeli drama, Jessica Chastain and Sam Worthington do sexy spy stuff in East Berlin on the trail of an obvious fictional analogue of Dr. Mengele. 2008’s Defiance, based on the true story of Belarussian Jews who formed a small partisan army during the 1940s — in the film’s telling, training up their more nebbish brethren — offers up as its ultimate symbol of the Jews who did fight back the blond-haired, blue-eyed Daniel Craig atop a white horse.

“The only blood I care about is Jewish blood,” says Craig’s Mossad agent in Munich. At the time of that film’s release, he had just been anointed the new James Bond. His rage and viciousness in defense of the… Jewish people? Israeli state? is established in Steven Spielberg’s film as a queasy warning for Bana’s Avner, who is tasked with killing the (alleged) orchestrators of the Munich Olympic Massacre. Avner’s handlers frame this blood vengeance as a morally just response to an existential threat. His mother tells him that he is the fulfilment of her wandering generation’s dream of a homeland. Spielberg and screenwriter Tony Kushner put a twist on the motif of “home” whenever Avner dons an apron to cook epic feasts for his unit of assassins. Munich, in its operatic ambivalence, documents a crisis not of faith but of masculinity, embodied in Bana’s heaving hairy chest, the heavily sexualized killings, and the physicality of the Israeli Olympians in Munich, who were wrestlers and weightlifters but nevertheless herded into an enclosed space and slaughtered.

Some of the historical reprisals shown in the film overlap with the time in the late ’70s during which three separate movies were rushed into production about Operation Entebbe. At Entebbe Airport in Uganda, IDF commandos raided a jetliner that had been hijacked by Palestinian and German guerillas en route from Israel to Paris, rescuing hostages which included Holocaust survivors. The only military casualty was commander Yonatan Netanyahu, Bibi’s older brother, forever enshrined as martyr and badass. Richard Dreyfuss played him in the ABC television movie Victory at Entebbe (1976). The one we watched in Hebrew School was Irvin Kershner’s Raid on Entebbe (1977), with Charles Bronson as the operation’s ground commander, Brigadier General Dan Shomron. Operation Thunderbolt (1977) was a Golan-Globus production which the Israeli filmmakers later remade in 1986 as The Delta Force with Chuck Norris.

“Israeli sabras believed in heroes rather than victims and martyrs,” Ellis writes. “For them, six million Jews should have become an Army of insurrection.” Victimhood is a psychological dilemma, and a narrative one as well, to the extent that the two can be decoupled. Just ask Spielberg, whose engagement with Jewish trauma prior to Munich was a Holocaust movie centered on a good German who was in a position to Do Something. Passivity is hard to endure and hard to dramatize; in both cases it’s a problem of identification. As a young reader, the two books which made the terror and gravity of the Holocaust emotionally vivid and legible to me were Anne Frank’s diary, of course, and Number the Stars, Lois Lowry’s Newbery Medal winner about a young Danish girl who participates in her nation’s rescue of its Jews. It was awe-inspiring to imagine Annemarie Johansen, Lowry’s little Schindler, mustering the bravery of a Resistance fighter. I much preferred it to the story of the introspective Jewish girl who waited in an attic in vain. In Nordau’s “muscular Judaism” speech, he mourned how “In the narrow Jewish street our poor limbs soon forgot their carefree movements. In the dimness of sunless houses, our eyes began to blink shyly. The fear of constant persecution turned our powerful voices into frightened whispers.” But, he promised, “our new muscle Jews [can regain] the heroism of our forefathers.” That’s a promise of narrative agency, and with agency comes another kind of neurosis.

In Munich, Avner’s unit participates in the killing of bystanders and argue about how far they can pursue vengeance while remaining righteous. Such debates, often in the form of excruciating pilpul-esque dialogue exchanges, are a recurrent feature of the Don’t Fuck with the Jews genre, and faithfully reflect a discourse around Israel and Palestine forever fixated on ethical hairsplitting — acts of provocation, calibrated retaliations, legitimate targets, and “precision strikes” whose precision is primarily rhetorical. More generally, the performative preoccupation with justification recalls the “shooting and crying” trope in Israeli culture, in which the guilty feelings of an individual soldier affirm what Ellis calls the “innocence” of the Israeli project.

No such anguish obtains in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglourious Basterds, in which Hitler and Goebbels are entrapped and killed in a movie theater where flammable nitrate film is the allegorical Zyklon-B. This alternate history Holocaust revenge-porn fantasy also boasts a squadron of marauding American Jewish soldiers, played mainly by the types of character actors who would be the schlemiel in most WWII platoon movies. Horror movie director Eli Roth plays “The Bear Jew,” who administers baseball-bat beatdowns to German officers. In The Atlantic, Jeffrey Goldberg pondered whether the film was Good for the Jews. On the one hand, it reminded him on one hand of the dreams of “righteous Jewish violence” that were his outlet for dealing with the anti-Semitism he encountered in his adolescence, which ultimately inspired him to join the Israeli Army. On the other hand, it also reminded him of the way some of his fellow IDF soldiers would “[beat] the hell out of Palestinians because they could.” Goldberg ultimately disavowed the film’s most gleeful acts of sadism — like scenes of Jews carving swastikas into Nazi foreheads — as “[not] the Jewish thing to do.” Perhaps, uncomfortable seeing how much fun an outsider was having riffing on decades of media celebrating militant, masculine Israel, Goldberg worried that QT was blowing up his spot.

Goldberg showed foresight to flinch at Tarantino’s flattery. The year before Inglourious Basterds, another juvenile genre cinema icon offered his own take on muscular Judaism: Adam Sandler, whose Mossad super-agent in You Don’t Mess with the Zohan is a cheesy, hairy sex god. Zohan brags about pulling off commando raids without any collateral damage — he shoots without crying — but nevertheless runs off to New York to become a hairdresser. (Like some faygele? his Six-Day War veteran father wonders.) There he falls in love with a Palestinian woman who had to leave her homeland because of the violence, hatred, and extremism on “both sides.” She says this three times in a single scene, though when John Turturro’s PLO hero/terrorist repeatedly slaps Zohan and implores him to “fight back,” the film is letting you know Who Started It.

But a decade on, such precision about The Jewish Thing to Do might seem passé. On the satirical docuseries Who Is America?, Sacha Baron Cohen played a much harsher parody of the kind of Jew you don’t want to mess or fuck with: Erran Morad, with his steroid-choked vocal cords and waxen, almost immobile GI Joe face. In this Mossad drag, Baron Cohen secured interviews with simpatico U.S. movement conservatives, drawing out absurd case studies in the hyper-militancy and anti-Arab bigotry that unites the American right and the Israeli government, appealing to a liberal audience growing ever more skeptical of the latter.

Like the Zohan, Munich’s disillusioned Avner eventually moves to New York City. So did Peter Malkin, one of the Mossad agents who captured Eichmann, though Operation Finale, the 2018 film about the raid, ends in Jerusalem in 1961, while he still lived in Israel. “A trial resembles a play in that both begin and end with the doer, not with the victim,” wrote Hannah Arendt. In Eichmann in Jerusalem, she described the Israeli government presenting a “lesson,” as she said, in “how the Jews had degenerated until they went to their death like sheep, and how only the establishment of a Jewish state had enabled Jews to hit back, as Israelis had done in the War of Independence, in the Suez adventure, and in the almost daily incidents on Israel’s unhappy borders. […] Jews outside Israel had to be shown the difference between Israeli heroism and Jewish submissive meekness.” Operation Finale shows victims becoming doers. Malkin (Oscar Isaac) infiltrates Argentina to kidnap Eichmann with a team, and on behalf of a country, still bearing the scars of the Holocaust (sometimes literally, in the form of multiple concentration camp tattoos at which the camera respectfully gapes). Throughout, he is haunted by flashbacks of his sister’s death in the Holocaust, each one offering a different painful vision of her unknown fate. It’s after witnessing Eichmann’s trial that he’s finally able to imagine saying goodbye to her and feel the burden of history lifted — a personal and national catharsis.

In these flashbacks is a wan echo of Munich, in which Avner is likewise overcome at crucial moments with mental images of the Olympic hostage crisis. These climax along with the film in one of the most notorious scenes of Spielberg’s career: a montage intercutting the horrific and drawn-out massacre of the Israeli Olympians with Avner’s thrashing, sweaty sexual intercourse with his wife. This scene was much derided upon the film’s release, and still is today, but it has an incredible potency. It’s off-putting and unforgettable, and gets to the heart of the anxiety and contradictions of the Jewish diaspora’s relationship to Israel. It depicts the return of a repressed trauma that Spielberg’s muscular protagonist can’t overpower, a pain he can’t fuck away, Jewish suffering and Jewish strength suspended together in a mental maze from which there is no exit.

Thanks to Keith Uhlich, Adam Katzman, and Noah Kulwin.

0 Commentaires