LOS ANGELES — On April 9, 1906, Reverend William J. Seymour held a prayer meeting at Richard Ashbury’s home on Bonnie Brae Street in downtown Los Angeles. For days he had been preaching about how baptism in the Holy Spirit allowed for direct experiences with the divine, as evidenced by the ability to speak in tongues. Although some criticized his teachings as heretical nonsense, his meetings attracted large crowds that cut across racial, class, gender, and age barriers. Eventually, the Reverend and his believers moved to a larger building on Azusa Street, where revivals — gatherings that aid in an individual’s spiritual reawakening after a period of moral neglect — occurred over the next three years.

Historians point to these meetings and Reverend Seymour’s sermons as the cataclysmic force that ignited the Black Pentecoastal movement. The Reverend’s revivals offered a refuge from the harsh realities of 20th-century United States, a place that did not seem to replicate society’s violent inequalities. (As the movement grew and solidified into different denominations, this utopic vision was dashed by usual suspects: patriarchy, racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia.)

Otherwise/Revival, the new group exhibition at Bridge Projects, gathers 31 artists whose works tremble with references to the histories and personal experiences of Black spiritualities — from the Black Pentecostal Church to Catholicism to a synergetic mix of beliefs. Curated by Jasmine McNeal and Cara Megan Lewis, the show explores the breadth of Black praise and worship. Although most of the work was made in the past year, I was awed by the overwhelming sense of history, how the exhibition traces the contours of Black spiritual thought from Louisiana plantations to Azusa Street to our present moment.

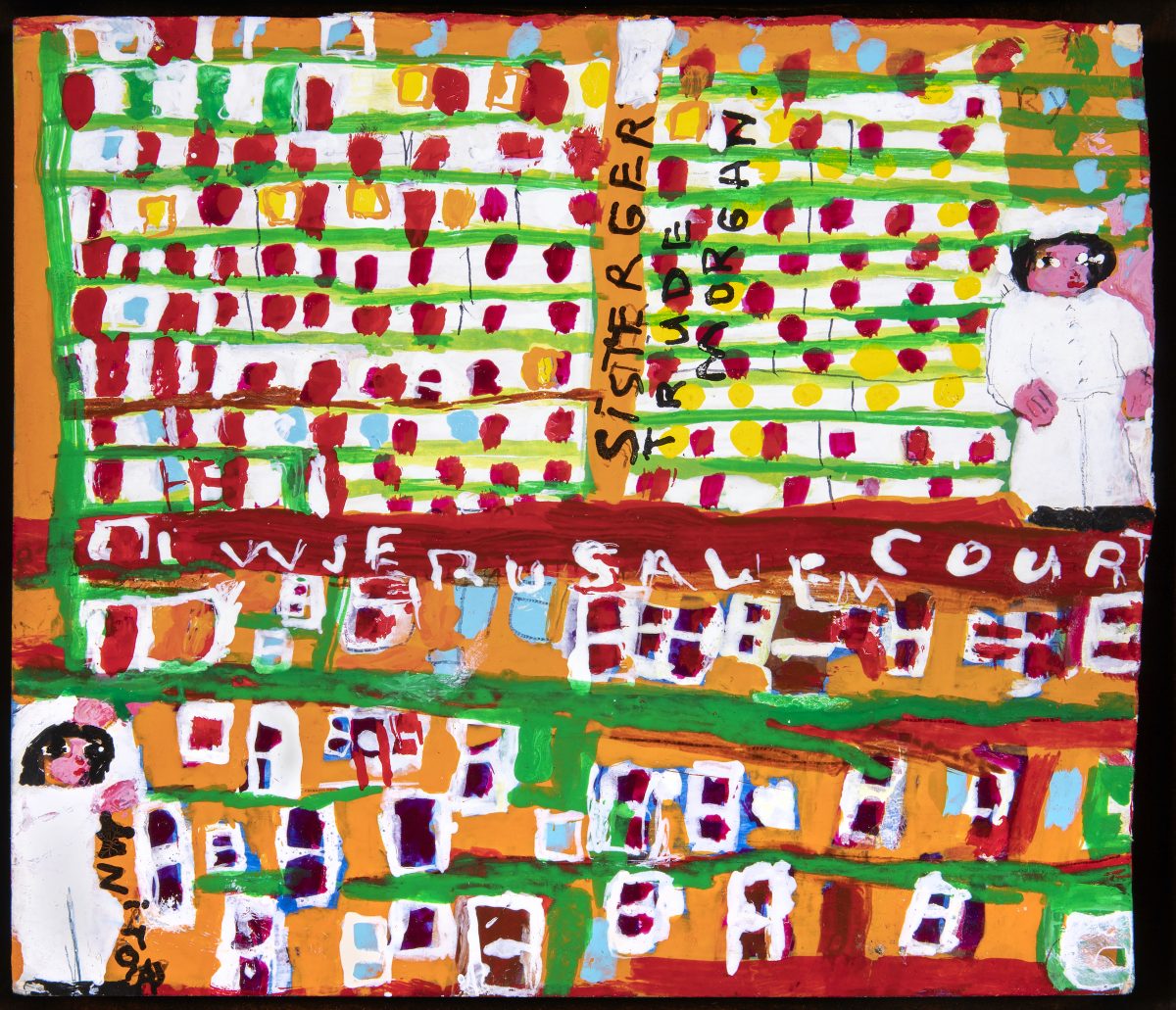

Some artists, like Clementine Hunter and Sister Gertrude Morgan, painted scenes that are pulled directly from their lives or religious studies. Hunter’s oil painting, “Coming from Church,” depicts women and young girls in bright dresses and hats leaving a white church, the flat landscape a swirl of blue-lavender and pink. The scene celebrates the everydayness of life, while also hinting that the threshold between sacred and secular exists everywhere.

Other artists twist and transform religious iconography. Kehinde Wiley and Mark Steven Greenfield appropriate popular figures like St. Nicholas and the Virgin Mary, recasting them as a young Black man and the mother of a slain Black son. Their paintings, infused with the aesthetic grandeur of Catholicism, speak to the ways that Black existence is attended by both the miraculous and the disturbing, a constant negotiation between joy and grief.

The show borrows its title from Blackpentecostal Breath: The Aesthetics of Possibilities, a book by professor and artist Ashon T. Crawley, who is also featured in the show. For Crawley, “otherwise possibility” refers to a space of expansive imagination, where alternative modes of living flourish. The elements of the Black Pentecostal church — the music, the whooping, the ecstatic presence — illustrate this possibility of becoming and unbecoming, this continual search for mutually beneficial togetherness. In a similar way, the artists in Otherwise/Revival enact their own surrender and freedom, allowing us to tap into the spiritual bonds coursing all around us.

Otherwise/Revival, curated by Jasmine McNeal and Cara Megan Lewis, continues at Bridge Projects (6820 Santa Monica Boulevard, Hollywood, Los Angeles) through July 31.

0 Commentaires