When I first saw Choong Sup Lim’s work on Sunghee Lee’s cell phone, I had two thoughts, which I kept to myself. The first thought was whether or not Lim was familiar with the whoong-sup-ork of Richard Tuttle. The second was about Lim’s use of a soft gray green that reminded me of Korean celadon ceramics or “greenware” made during the Goryeo Dynasty (918–1392 CE).

Lee, the director of Gallery Hyundai New York, was going back to Lims’s studio the following week and asked if I was interested in meeting her there. After I said yes, she warned me that Lim lived and worked in the same place and that he had no storage.

A few days later, Lee gave me Lim’s address and set up a meeting time. By then, I had learned that Lim was born in the farming town of Jincheon, Korea, in 1941, and earned his BFA from Seoul National University in 1964. In 1973, he moved to New York, where he has mostly lived and worked ever since. Also in 1973, he was awarded a Max Beckmann Memorial Scholarship to study at the Brooklyn Museum Art School. In 1993, when he was in his early 50s, he received his MFA from New York University.

During this time, Lim’s work was shown in a number of American galleries, including OK Harris, Grace Borgenicht, and Sandra Gering, while he continued to show regularly in Korea. Holland Cotter, Marjorie Welish, Robert C. Morgan, Jonathan Goodman, and Hyperallergic Weekend Co-Editor Thomas Micchelli had all written about his work. Cotter ended a New York Times review (July 25, 1997) of Lim’s show at Sandra Gering with this observation:

The results are offbeat, but a shade too hermetic to hold the attention.

Cotter’s statement did nothing to dissuade me as by this time I was already hooked. It was while looking up Lim’s publications that I learned he had had an exhibition, Luna, and Her Thousand Reflections, at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Seoul, Korea (December 12, 2012–February 24, 2013), and that he worked across many disciplines: painting, drawing, sculpture, found objects, and installation. One of the authors who contributed to the catalogue was Richard Tuttle.

The title of Tuttle’s contribution is “Behind the Suffering.” Two sentences jumped out. The first is: “It’s all the same; we are looking for healing.”

The second the is final sentence of Tuttle’s tribute to “a friend, who touches [his] soul”: “With a certain attention, we have everything he has without the suffering.”

A week later, I went to Lim’s storage-studio-residence. I sat down near another chair, a table, and a bed, and began looking around. The place was packed with years of work; it took a long time to begin discerning what was there. As my eyes darted around the room, like a frenzied fish, I was not sure where to begin.

When Lim was a student in Korea, he found the teaching too rigid. He told me that he wanted to go to New York because, in his mind, the art was not governed by strict rules. At the same time, Korean artists of the previous generation were interested in materials and processes, which set them at odds with the repressive government of Park Chung-hee, who declared martial law in 1972. I don’t think Lim’s desire for freedom was purely aesthetic; rather, I think he saw his art and life as bound together.

The connection between art and life was central to the artists of the Dansaekhwa movement. The term means “monochromatic painting.” Although the Dansaekhwa artists shared something with American Minimalist painters, they employed materials (burlap, barbed wire), processes (pushing paint through the burlap’s loose weave and painting strokes that they never altered, painted over, or removed), and a spiritual belief system that was fundamentally different from those of their Western counterparts. All of this Lim brought with him to America. How his work evolved after he got here is what caught my eye.

Lim pointed to a small painting that I was looking at and said it was painted on carpet, which he liked because it was tough and durable. Even though I had no idea what the subject of the painting might be — and I believe there is always a subject in Lim’s work — the painting held my attention. He began showing me others, from a stack.

Behind me, on the wall, he had hung four rows of drawings. Some were calligraphic, but, unlike ink drawings, they were made over time in oil paint and other materials. He seemed to want to slow time and consider the relationship between nature and society. He showed us a drawing of a hand and talked about his mother, who died when he was young, and a particular memory of an old Korean children’s song that has the line, “Hey toad, hey toad, I’ll give you an old house, you give me a new house….”

According to Lee, children usually sing this song while playing with soil: putting the soil onto their hands, making it firm, and then drawing their hands out of the soil. She also translated what Lim had written on the drawing: “It is a toad’s house when you take your hand out from the soil; this is a sculpture that I made with my mom.”

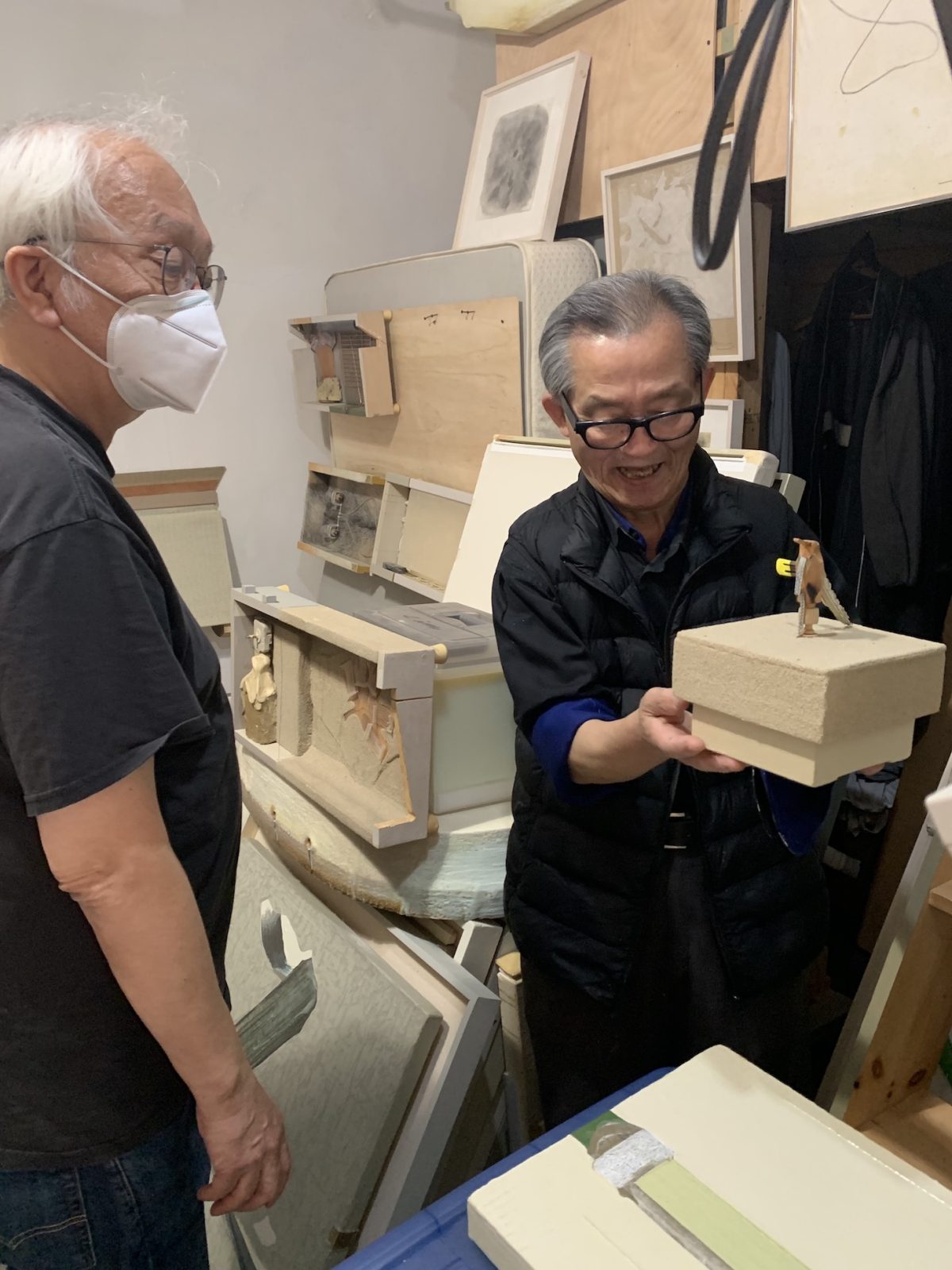

In another room in Lim’s maze-like home-studio, he showed me a bird made out of things he had collected. This was the first I had seen of Lim’s whimsical side. After a tour of his place, we returned to where we started, and Lim began showing me his notebooks. He keeps a diary, writing on a single sheet of white paper, usually in Korean. Each page is dated, placed in a plastic sleeve, and put in a three-ring binder.

Lim also talked about his shaped canvases, which had more in common with Tuttle’s abstract objects than, for instance, Frank Stella’s shaped paintings of the 1960s and ’70s. I was struck by the way Lim’s shaped paintings, which were usually monochrome, protruded awkwardly off the wall. I remembered a notebook page that Lim had shown us. On it he had written in English, under the Korean: “The barley sack which has been borrowed from somebody.” According to Lee, this is a Korean idiom referring to a person who doesn’t get along well when talking in groups or socializing, and quietly sits alone. After living in America for nearly 50 years, this was how Lim described himself.

0 Commentaires