“If we believe that the spread of nuclear weapons is inevitable,” President Barack Obama postulates, “then in some way we are admitting to ourselves that the use of nuclear weapons is inevitable.” This audio clip plays as a voiceover towards the end of Smriti Keshari and Eric Schlosser’s experimental film the bomb (2016). Obama’s words illustrate the register that frames discussions around the proliferation of nuclear weapons. In contemporary political discourse, nuclear weapons are discussed in formal, geopolitical terms — a global jockeying between nation-states underneath the obtuse machinations of diplomacy. Within Keshari and Schlosser’s film, Obama’s staid phrases are inscribed as a conceptual plea to reimagine the discussion around nuclear weapons, one where disarmament is a tangible possibility.

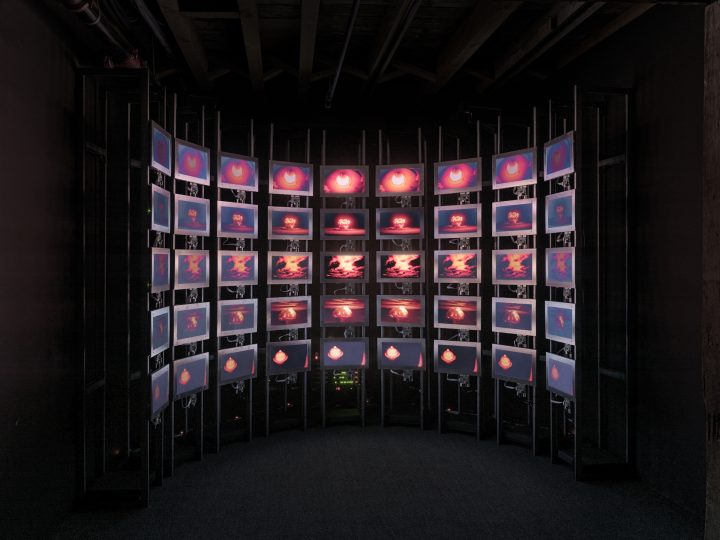

At Pioneer Works, the bomb is displayed on 45 iPad-sized screens arranged in a semi-circular grid at the back of a small room. To view the film, you can sit on the ground or small cushions, four or five feet from the monitors. This cramped room departs from the massive, 360-degree screens of the original screenings, billed as “immersive” experiences. Likewise, in this installation, too-small monitors make it difficult to read the minimal text that does appear to contextualize the archival footage.

Over the film’s 59-minute runtime, Keshari and Schlosser offer a visual archive, recycling and remixing documents, footage, and audio from the approximately 80 year history of nuclear weapons. An original soundtrack by electronica group The Acid heightens the emotional impact of the footage, pacing the film with the rapid BPM of the music. Flashes of U.S. government advertisements (presumably from the 1950s) for nuclear fallout preparedness are rendered uncanny and eerie when played against the electronic score, with jingles like “Duck and cover” warped as if sourced from a Twilight Zone episode. At turns, different image patterns appear across screens — diagonally or alternating between rows — to emphasize a particular moment. Silence envelops the room as the screens turn blank and black in unison to represent the detonation of nuclear bombs in Japan during World War II. Watching the bomb, horror, anger and grief washed over me.

This is precisely the strength of Keshari and Schlosser’s film; by opting for a nonlinear, non-narrative approach to the history of nuclear weapons, they are able to reach at the affective registers of debates surrounding them. The bomb leaves the viewer with no answers but instead imparts a feeling of dread.

Still, at other times, this approach stunts legibility. While a quick google search reveals that Obama’s quote is sourced from a 2009 address in Prague, much of the footage in the film is left out of context. Likewise, the film leaves out how one might apply this knowledge in such a way as to affect the elite political machinations which make decisions around nuclear policy. Instead, a substantial amount of time in the film is devoted to distorted mushroom cloud footage accompanied by rattling bass drums and operatic synths, perhaps explaining why a 2017 screening at the music festival Glastonbury was appropriate.

Notably, the film highlights several instances (and news coverage) of accidental launches of nuclear weapons, calling into question the very notions of “control” or “safety” when it comes to nuclear devices. the bomb, as a piece of political activism, seems to circle around the same fallacy of control with respect to how the proliferation of nuclear weapons has long since escaped the individual or individual nation-state’s grasp. Earlier in the same 2009 address, not included in the film, Obama notes, “as more people and nations break the rules, we could reach the point where the center cannot hold.” the bomb, in its poetic form, is in some ways a fitting representation of the discourse around nuclear weapons and disarmament precisely due to its opacity, fragmentation, and contradictions.

the bomb: Smriti Keshari and Eric Schlosser continues through May 23 at Pioneer Works (159 Pioneer Street, Red Hook, Brooklyn). The exhibition was curated by Gabriel Florenz.

0 Commentaires