LONDON – One of the first works on display in Jennifer Packer’s current solo show at the Serpentine Galleries is a double portrait of two of the artist’s friends and fellow painters: Jordan Casteel and Tschabalala Self. Titled “Jordan,” the 2014 work is painted in a palette of lucid browns and greens, with areas of close precision and others of near-abstraction. Almost every element in the painting is doubled: the pairs of artist sketches on the wall, Self’s red-and-black baseball cap, and the figure of Casteel, whose reclining pose is mirrored in that of a large-scale nude hanging behind her.

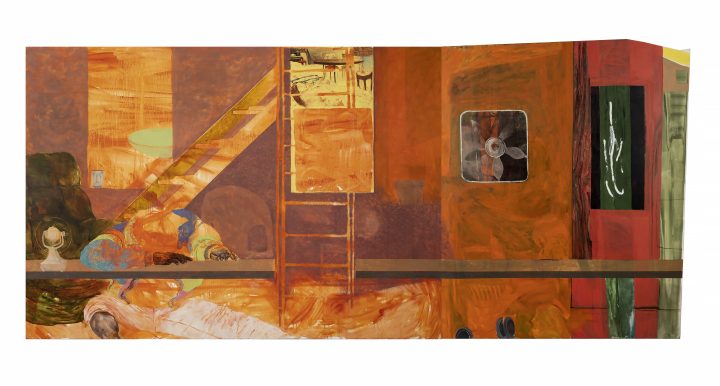

Packer’s gaze itself is doubled. She looks back at a history of art that has excluded and exploited Black people, and uses it to create works that celebrate contemporary Black life in its uniqueness. These celebrations are not always joyful, however. The culmination of her Serpentine show is a monumental canvas — three meters by four — titled “Blessed Are Those Who Mourn (Breonna! Breonna!)”, painted in memory of Breonna Taylor, the 26-year-old Black woman who was shot and killed by a group of plainclothes police officers in her own home in March 2020. The painting’s bright yellow colours are at odds with the anguished scene it portrays: a half-naked man lies on his couch, turning his head away from the viewer in grief. On the left-hand side of the canvas paint drips down in long cascades, as though weeping.

An awareness of death pervades the exhibition. Apart from a couple of interior scenes, Packer’s paintings are all still lifes and portraits — two genres historically rooted in the notion of human transience: one used to remind humans of their mortality, the other a means of immortalizing them. For Packer, the two genres are less easily distinguishable. The floral still life “Say Her Name” (2017) is a kind of posthumous portrait of Sandra Bland — another Black-American woman who died as a result of police brutality. The funerary bouquet is painted in feverish brushstrokes and splashes, so that you can only just make out the petals and leaves. Other works, such as an untitled charcoal drawing of a bunch of roses, play even more with the limits of our perception: squint and you’ll miss it.

The exhibition’s Biblical title — The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing — is a fitting tagline for Packer’s distinctive form of figurative abstraction. Her astutely observed details — a typewriter, a fan, a pair of odd socks — are interspersed with swathes of paint that express aspects of human experience that lie beyond representation. As the Bronx-based artist’s first institutional solo show outside the US, this exhibition is an astonishing debut. The 35 works, hung non-chronologically through the galleries, range from paintings made in 2011 while Packer was studying at the Yale School of Art, to those finished just a few weeks prior to installation. They could hardly be more contemporary, and yet you sense that they won’t lose their relevance any time soon.

Jennifer Packer: The Eye Is Not Satisfied With Seeing reopens today (May 19) at the Serpentine Galleries (Kensington Gardens, London, England) and continues through August 22. The exhibition is curated by Melissa Blanchflower and Natalia Grabowska.

0 Commentaires