At 1am on December 25, 1980, four burglars entered the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes in Buenos Aires, Argentina, through a gap in the roof, and took 16 Impressionist works and seven early Chinese sculptures. The heist was peculiar for its seamlessness: ladders presumably left by construction workers made it easier for the thieves to break in. Two night guards keeping watch that night were tortured and arrested by state police, but no one has ever been charged with the crime to this day. And according to anecdotal accounts by witnesses, an army truck was seen parked outside the museum.

For decades since, a rumor has been percolating throughout Argentine art circles: the raid was staged by the nation’s vicious military junta, and the stolen works — worth over $2 million — were sold to buy weapons from Taiwan to fund the 1982 Falklands War.

Anja Shortland, a professor of political economy at King’s College in London, expounds the theory in a forthcoming book titled Lost Art: The Art Loss Register Casebook, to be published in June of this year. The Museo de Bellas Artes haul is one of 10 intriguing cases examined by Shortland that involve the Art Loss Register (ALR), a private database of lost, stolen, and looted art, antiquities, and other collectible objects reported by victims of the theft and governmental entities. Established in the 1990s, the database now holds more than 700,000 entries and has become an industry standard for conducting due diligence in the notoriously murky art market: if a work shows up on ALR, it will be difficult to sell — at least publicly.

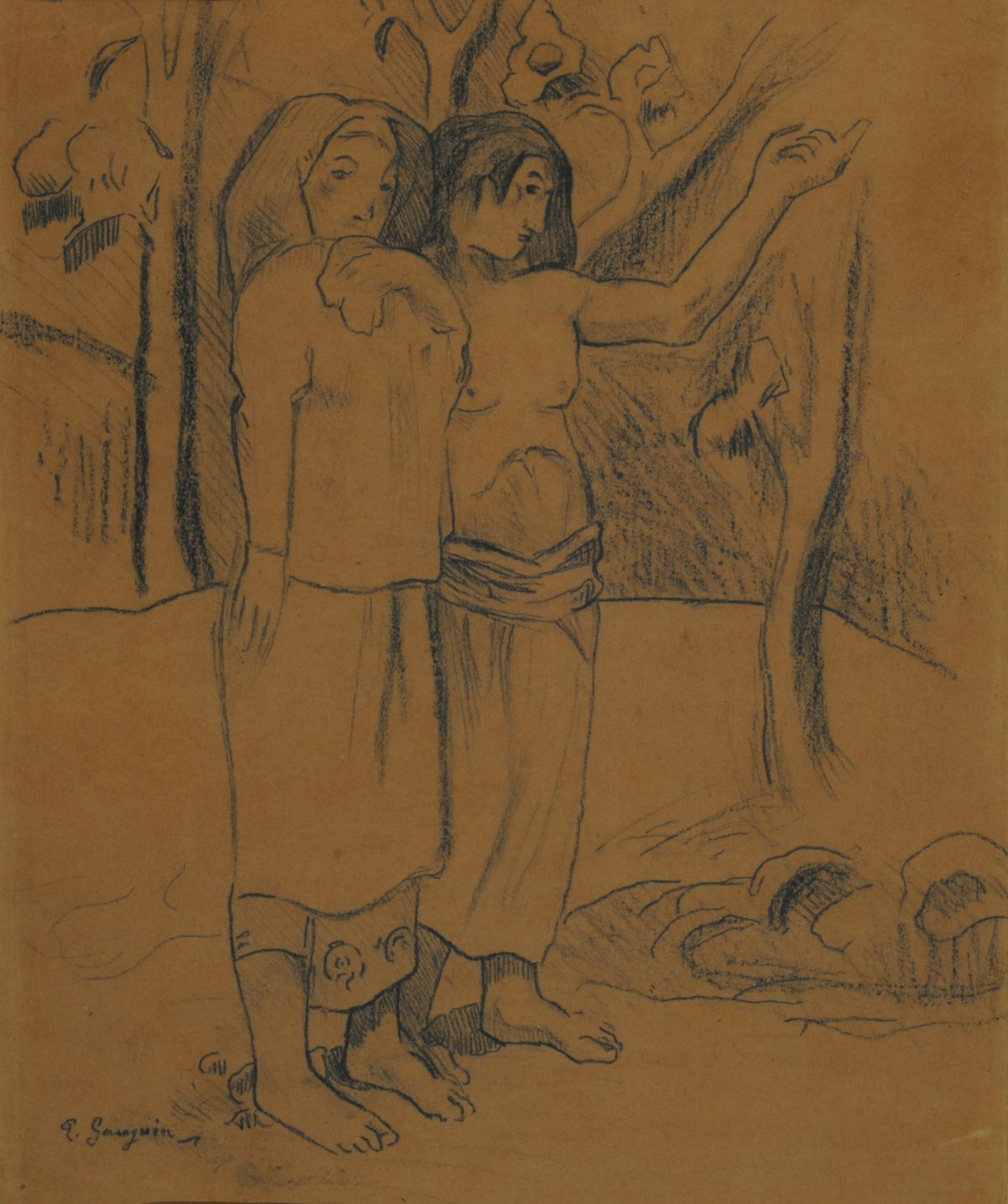

The trove taken from Bellas Artes came from a collection of Impressionist and modern art amassed by Antonio Santamarina, a wealthy Argentine cattle rancher and conservative politician. Much of it was sold at auction while he was still alive; upon his passing, his widow reluctantly donated a group of remaining smaller paintings and drawings by artists including Cézanne, Degas, and Renoir to the museum.

In May 2001, a search request came to ALR from Sotheby’s. A collector in Taipei had approached the auction house to appraise several Impressionist pieces that matched the works stolen in 1980. The database’s research team immediately alerted the museum of their findings and requested their authorization to initiate the art’s return.

But the negotiations were stagnated, in part by Argentina’s profound economic crisis — 2001 was the year the country defaulted on $93 billion of its sovereign debt — and by the resistance of the owner, who insisted he had purchased the works in good faith. “Mr. L,” as he is referred to in Shortland’s book, was a Taiwanese arms dealer.

Argentina’s Military Junta rose to power in a March 1976 coup that overthrew President Isabel Perón. The bloody dictatorship that ensued, led by General Jorge Rafael Videla, ushered one of the darkest periods in the nation’s history: the Guerra Sucia (“Dirty War”), a genocidal campaign that led to the disappearance and assassination of around 30,000 citizens, many of them left-wing activists targeted as enemies of the state.

In 1982, to distract from growing upheaval and civic unrest, Shortland writes, the Junta decided to challenge Great Britain over possession of the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), an archipelago off the coast of Argentina in the Atlantic Ocean that was usurped by the British in 1833. Though the Bellas Artes heist had seemed dubious from the very start, the identity of the works’ eventual owner boosted suspicions.

“The fact is, they turn up with a weapons dealer in Taipei, who seemed perfectly comfortable saying that they have been acquired legally,” Shortland told Hyperallergic. Taiwan, ALR’s director Julian Radcliffe said in an interview, was not among the countries that had imposed an embargo prohibiting the sales of weapons to Argentina during the Falklands crisis.

When Radcliffe initially approached the Museo de Bellas Artes to assist in the recovery of the works in 2001, the museum’s leadership vacillated, calling the operation a “very political problem.”

“ALR was dealing with a government that was in the throes of bankruptcy, and that had all sorts of political issues surrounding the question of who should be negotiating this, where the money should be coming from, if there is any money at all,” Shortland told Hyperallergic. “And certainly there seemed to be some people in the background who were going to be unhappy.”

As she writes in her book, “If the rumours swirling around the involvement of the military Junta in the theft were true, reclaiming the missing artworks might upset those who instigated the ‘theft.’”

The Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes has not yet responded to Hyperallergic’s request for comment, but the museum’s director, Andrés Duprat, told the local news outlet Infobae that “the theft was always suspected to have been organized not by external agents, but by powers from within Buenos Aires.”

After four years of labyrinthine back-and-forth, in November 2005, three of the works — two small oils by Cézanne and Renoir and a watercolor by Gauguin — were repatriated to Argentina. That particular trio had surfaced in a Parisian gallery, where the mysterious Mr. L had attempted to have them sold as soon as he learned that there was a chance they may be seized by officials and returned to Argentina. The restitution was arranged between Interpol, France, and the Argentine government, sidestepping the ALR, which had done much of the heavy lifting to facilitate the operation but ended up being paid just a fraction of its dues.

But the whereabouts of the remaining 13 Impressionist works, as well as the Chinese sculptures, remain unknown.

“We don’t know where they are, presumably they are,” Shortland said. “But they’re not coming off the ALR database unless the Bellas Artes museum tells them to take it off. So they’re still unsaleable in the open market.”

The chapter ends with an anecdote: during a steak dinner in Buenos Aires in 2005, after a presentation on ALR’s work at the Museo de Bellas Artes, Radcliffe’s host pointed to a man dining at a nearby table. “There is your thief,” he said. The government agent who had orchestrated the scheme was, presumably, dining in the same restaurant with them.

In an interview with Hyperallergic, Shortland said the theory that the Junta was behind the raid is not new. As early as 1983, an article by journalist Guillermo Patricio Kelly in La Prensa suggested a link between the heist and a paramilitary group led by Aníbal Gordon of the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance (known as the Triple A death squad.) Gordon, who was found guilty of crimes committed during the dictatorship, died in jail in 1987; neither he nor others linked to the squad were investigated for the Bellas Artes haul. Las year, on the 40th anniversary of the heist, the independent Argentine newspaper Gatopardo published an in-depth essay on the case, and in 2013, Patricia Martín García published Pasaporte al olvido: El caso del robo del Bellas Artes.

The story of the Santamarina trove is now gaining renewed global attention thanks to Shortland’s book. She is hopeful that the remaining works will be restituted.

“I have complete confidence that they will turn up, and someone will either get a bad surprise or they will just find out that these works are held hostage, not owned,” she told Hyperallergic.

“Even though there’s probably no legal way of recovery, there’s also no way in which the current holder will have any financial joy from these things,” she added. “It might take another 20 years, but eventually, they will come back, because the ARL doesn’t forget.”

0 Commentaires