Harmony Holiday had been preparing to stage a one-person play as her contribution to Made in LA: A Version, the Hammer Museum biennial. But, like so many plans made and unmade over the past year, she had to readjust the direction of her piece in the wake of COVID-19 closures. Holiday — a writer, dancer, archivist, and experimental director, and author of numerous poetry books, including Hollywood Forever (2017) — switched up mediums, turning an excerpt of the text into an impressionistic short film. With the reopening of museums in April, audience members can finally experience “God’s Suicide,” an elegiac loop inspired by James Baldwin’s five suicide attempts.

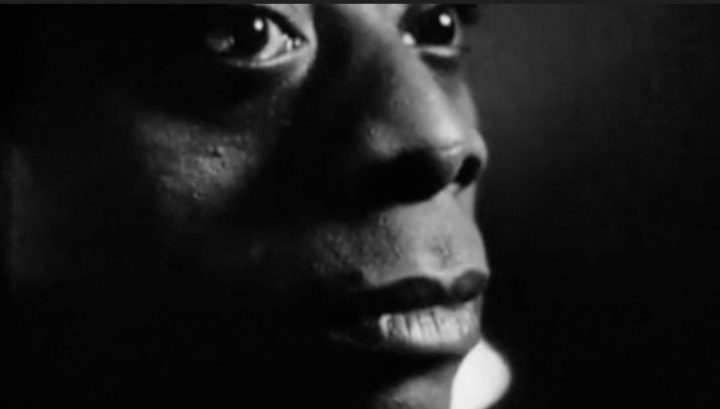

Framed as a letter to his dear friend Eugene Worth, the film presents edited archival clips of Baldwin set to a voiceover by actor Larry Powell, who delivers a tender and wounded performance as the writer. Some of the themes coursing through “God’s Suicide” appear in Holiday’s 2018 essay, “Preface to James Baldwin’s Unwritten Suicide Note.” Holiday shuffles together moments from Baldwin’s public life (appearing as a guest on The Dick Cavett Show; as a talking head in various documentaries; strolling the streets of Paris), an associative spiral that is more concerned with the meanings held in the curve of a hand or the sharpening of a glare. “Make that leap with me,” Baldwin/Powell implores. Though the film is projected on one of the gallery’s white walls, it can feel like you’re gazing over a precipice, transfixed by rhythms of the restless water foaming below.

Baldwin was haunted by the death of Worth, who committed suicide in 1946 by jumping from the George Washington Bridge. As Holiday notes in her essay, “In almost every one of his novels there is a suicide or a kind of ego-death that mimics it.” Throughout his own life, the writer experienced severe depressive episodes and suicidal thoughts. His biography is littered with attempts and near-attempts — in 1949, after a demeaning night in jail; again in 1956, following a fight with his lover, Arnold, and a few weeks after that, in Corsica. This facet of Baldwin is rarely acknowledged in mainstream accounts, a sanitization that deprives Baldwin of his prickly contradictions and emotional fragilities.

We spoke to Holiday about the typecasting of Black artists, using archives as an intervening force, and how Baldwin has ultimately been misunderstood.

***

Hyperallergic: What first drew you to exploring Baldwin’s depression and suicidal ideation, and how that informed his creative outlook?

Harmony Holiday: There’s a long tradition of making Black artists into what Jimmy Baldwin himself once called, in dismay, “exotic survivors.” That position, that typecasting — using men and women as cultural props — flattens their potential and serves them neatly to neoliberalism to be repackaged as politically expedient concepts and not full and complex human beings. I saw this happening with James Baldwin, a lot of name-dropping and fetishizing by people who likely hadn’t read any of his work or much of it but had seen the version of him in I Am Not Your Negro (2016), a stylized but functional melancholy. Then I read his biography, twice, and also listened to it as an audiobook. Each time I was stunned by the theme running through it that we never see in interviews or lectures of his: that he tried to take his own lifetime and again, was a genius, hysterical and distraught as he was grounded and exuberant.

That essay and this play are efforts to make vivid the inconvenient parts of this man who everyone claims to love but few take the time to understand.

H: How was the process of translating the play into a film?

HH: The vision had to be scrapped and recreated a few times. What we get is an excerpt from the play set to archival Jimmy Baldwin. The archival images of Jimmy gesturing and the beautiful voicing by actor Larry Powell come together in a way that I hope honors Baldwin’s ability to dance and lean and sway and gaze and pierce his way into what would otherwise be unsayable. His gift for language didn’t stop at words; the way he moved through space and time, those cadences in his form, are almost as important as the writing because they echo it and show how its true home is in him as a man who loved life as much as he struggled through it. Ultimately, I hope this film piece feels more like music than anything and captures the song and prayer that unfolds in the play.

H: Could you talk more about your approach to integrating archival materials into your work?

HH: In the film and in other works of mine, especially print and books, I’ve used archival sound and image to intervene, and to point out that these archives we have are the diaspora’s ruins. I want to engage the beauty beneath their rubble, to be curious and fumble through it, to dig ourselves out.

In the case of “God’s Suicide,” I really wanted the version of Jimmy Baldwin who still belongs to us to show up for us — a man who could laugh erratically, or throw shade, or look so pensive it aches to witness it — not just the one who always knew what to say after the state assasinated one of his friends, but also the Baldwin who was baffled and befuddled and wounded and perfectly real.

H: The visibility afforded to our Black cultural icons and heroes comes at a cost — commodification at one end, and literal death at the other. Are you more interested in privacy, or other alternatives, over visibility?

HH: I’m interested in both, how they circle and seduce one another, the cliché ‘grass-is-greener’ position we’re often forced into when we get too seen or too quiet. Part of the paradox and why it haunts Black identity so much is that the visibility we think of as valuable is often grounded in a lie about who we really are. The more public someone becomes, the more misunderstood and taken out of context and manipulated to fit the needs of the narrow collective imagination — as we have seen with Baldwin until now. Every interview possessed some version of the question: how does it feel to be gay, Black, and nearly dead? What was he supposed to do with that but become a caricature?

I think what I love most is exiting that binary and finding the source of real intimacy in any context. I hope I captured some of the gorgeous and very real sense of intimacy that helped Jimmy Baldwin survive all of the identity politics orbiting and preying on him. That intimacy can save some of us from the mire of spectacle when we make it our primary focus, because it’s where we safeguard real, loving attentiveness. That part is worth living and dying for.

“God’s Suicide” by Harmony Holiday is on view in Made in LA: A Version at the Hammer Museum (10899 Wilshire Boulevard, Westwood, Los Angeles) and Huntington (1151 Oxford Road, San Marino, Calif.) through August 1.

0 Commentaires