LOS ANGELES — Tina Turner stands on a circular platform, face slick with sweat and triumph, eyes drinking in the crowd of screaming fans below her. The platform, separate from the main stage and the rest of the band, is attached to a metal crane that stretches out into a section of the massive stadium. From Turner’s vantage point, the audience looks like a sea of bobbing arms, greedy for her attention and presence. The performance clip appears briefly in Tina, the HBO Max documentary about the rock legend’s life and career. “When I’m on stage, and it’s like 20,000 people, then you know that it’s all worthwhile,” she said in an interview that plays during the clip, before coyly adding, “But there’s really a lot that goes on behind the scenes…”

In PRIVATE DANCER, Nikita Gale’s first solo show at the California African American Museum (CAAM), the multidisciplinary artist considers the work occurring behind the scenes, homing in on the objects and technologies that structure our experience of live performances, and how those materials can blur, extend, or limit the parasocial relationships between audience and performer.

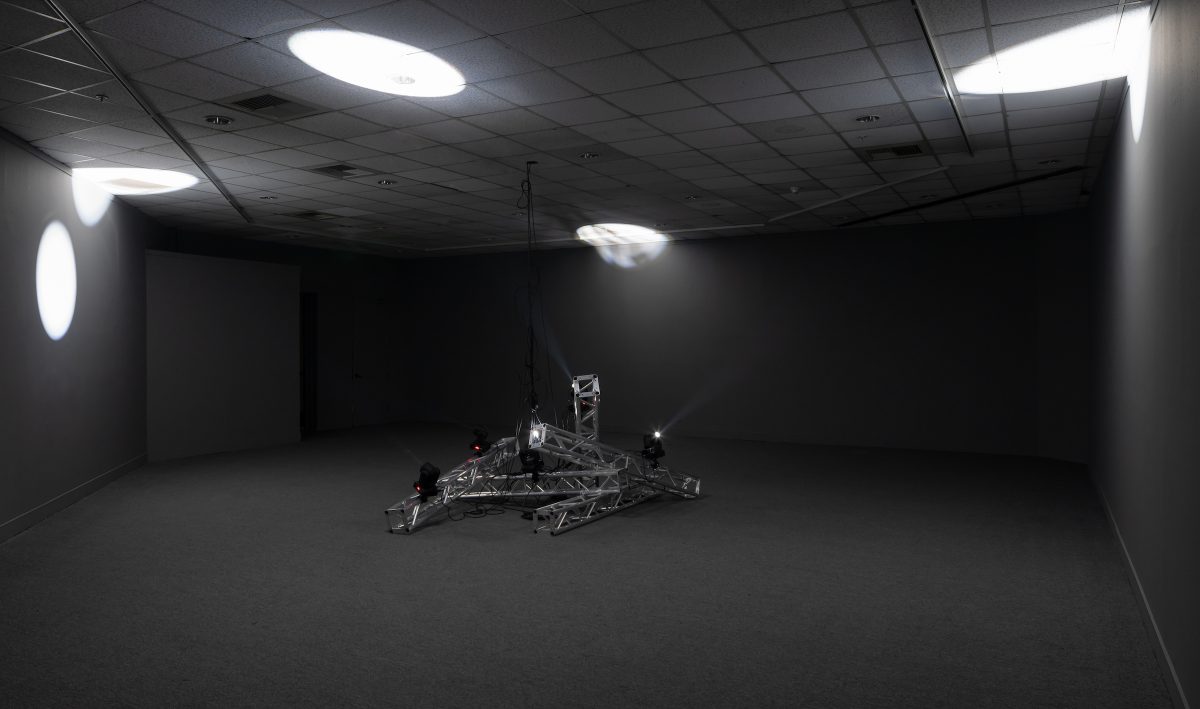

Situated in one of CAAM’s smaller galleries and curated by the museum’s executive director Cameron Shaw, Gale’s exhibition provides an inverse image to the boisterous concert footage that peppers the documentary. There are no hysterical fans or pulsing music. Instead, entering the gallery feels like crossing into a twilight dimension, where I am greeted by an enveloping darkness and a flurry of spastic spotlights. Five theatrical lighting trusses are arranged haphazardly in the middle of the room, as if the equipment were the leftover rubble from some accidental collapse. Various stage lights are set up on top of the trusses, whirring around and spilling their illumination across the room. They seem to be, like me, in frantic search of the absent performer.

Gale collaborated with lighting designer Josephine Wang to program lights that move in response to Turner’s 1984 album, Private Dancer. As I circle the sculpture, my attempts at guessing the song based on the rhythmic whirring is undermined by the disorienting lights and their mechanical squeaks. Although I try to slink around the room undetected, there are moments where the lights settle on my face or body, as if daring me to sing and dance in place of the missing figure.

Is this what Turner would see when strutting on the stage, not a specific audience but a phantom of light and noise? Turner is everywhere and nowhere in this piece, a potent symbol that allows Gale to meditate on the creative labor of public performances. “I think it’s very important to not lose sight of the physical exhaustion and energy that goes into performing,” the artist explained in an episode of the Carla Podcast.

Turner retired from public life in 2009, and to Gale, this decision signaled a rejection of the extractive practices of the music industry. PRIVATE DANCER recasts the singer’s retirement as a refusal, and a necessary act of self-preservation. Without a figure to absorb our projections, the ruins of performance blink on, leaving us to contemplate the invisible structures that mask the corrosive effects of being a musician.

Nikita Gale: PRIVATE DANCER, curated by Cameron Shaw, continues by appointment at the California African American Museum (600 State Drive, Exposition Park, Los Angeles) through May 9.

0 Commentaires