In many interviews, John Lees returns to three artists: Georges Rouault, Chaïm Soutine, and Milton Resnick. While they all share an extreme fascination with paint’s materiality, and the various ways this can be both manipulated and manifested, I don’t think Lees’s intense, lifelong preoccupation with them is purely about what they do with paint. The following statement by Rouault, who is all but forgotten in America these days, suggests to me the deeper bond that Lees feels with them:

Anyone can revolt. It is more difficult silently to obey our own inner promptings, and to spend our lives finding sincere and fitting means of expression for our temperament and our gifts.

“Interiority” is one of the words that the art world has never quite known what to do with, as it prioritizes the importance of subjectivity and the isolated individual rather than objectivity and collectivity. The other thing that Lees’s work brings home to me is that an expressionist painting need not be done fast, no matter how fluid the paint might look.

In his current exhibition, John Lees: New Work, at Betty Cuningham Gallery (March 26–May 22, 2021), I recommend the viewer check out the dates of each work. Having first seen Lees’s heavily worked paintings and worn drawings in the mid-1970s, and written a catalogue essay for his exhibition at Hirschl & Adler in 1986, I was sure that I had seen a number of these paintings in earlier iterations, and I was not wrong.

Done in oil on canvas, ‘Bathtub” is dated 1972–2010. I knew I had seen this impasto painting in an earlier state, but I was not sure how many times. Lees keeps going over his subjects, holding onto whatever brought him to a particular view, memory, or vision in the first place. We might never learn what memories and associations the bathtub provoked in him, but we don’t have to.

Lees’s paintings and drawings are deeply contradictory, which is what makes them human. A bathtub is where the defenseless and vulnerable individual sits partially immersed in water, alone and naked. It is where one goes to become clean. This hardly seems the case with Lees’s portly bathtub.

The rim and front are encrusted with dirty, round lumps of white paint. On the far right, a paint-caked gooseneck pipe rises from the interior of the tub, like a periscope, connoting that far more is hidden than seen. While the tub’s surface has been built up, the wall behind it has been worn down, particularly in comparison to the tub.

Lees’s signature process seems perfectly in tune with the subject of his paintings. By repeatedly returning to the same motif, and by building up as well as sanding down the painting’s surface, Lees attempts the impossible, which is to freeze a particular object, individual, or moment in time.

Made of worn globules of paint and eroded surfaces, often in muted colors, Lees’s paintings are deeply scarred records of time passing. He seems to want to stop time, and, in many works, honor a childhood home, even as he is compelled to recognize and even embrace time’s obliterating, corrosive power. In his traumatized surfaces, Lees discovers beauty while expressing rage and horror at its inescapable disfigurement.

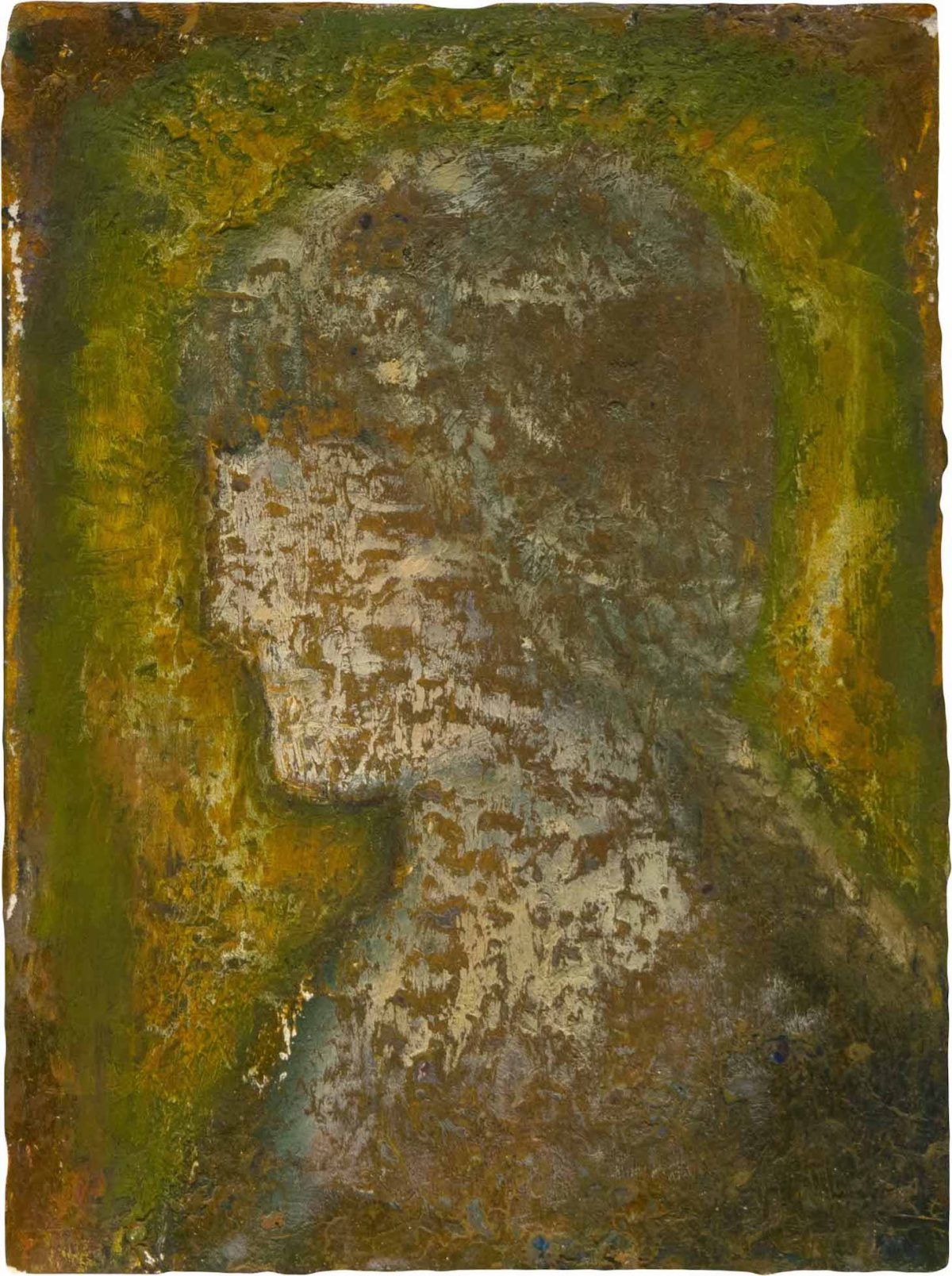

It is in his portraits and figure paintings of friends, admired individuals, and partners that Lees’s brew of contending feelings reaches an excruciatingly powerful pitch. In “Profile (Sandy)” (2013–19) — one of the great paintings in the exhibition — it is as if we are looking at a worn-down fresco, a surface abraded by time. Sandy, who is seen in profile, has been ravaged, her facial features stripped away. If we cannot stop time, and Lees knows that he can’t, perhaps one alternative is to honor its caustic effects.

In subversive counterpoint to portraiture, which is about preservation and resemblance, about holding time at bay, Lees addresses time’s pervasive effects. A select show of portraits by Lees, Francis Bacon, and Frank Auerbach would offer different ways of contemplating portraits that go beyond resemblance (or image) and investigate the bond between flesh, memory, seeing, paint, and time. In his portraits, Lees more than holds his own against these two older, highly celebrated English counterparts.

One thing that strikes me about Lees’s oeuvre is that it is an unapologetic gathering of private fixations. We never learn who Sandy is or why Lees devotes so much effort to a bathtub from long ago. And yet, in dedicating decades to a painting, and working in a way that evokes time and decay, he rejects society’s marketing of beauty, flawlessness, and idealized physical fitness, as well as its aesthetic counterparts. If anything, one detects a certain delight on Lees’s part in knowing that time erases us all — yet it does not necessarily terrify those who recognize that they are on the brink of disintegration. A million selfies won’t save you.

A diaristic artist, who often dates each time he works on a drawing, as he does in “Sitting in One Place (Scroll)” (2001–21), which is 13 by 95 inches, and made of joined sections of paper, Lees seems to be looking at his everyday life, rather than the past. The black cat we see lying in the foreground on the far left becomes, years later, the outline of a cat seated, looking into the drawing of the landscape on the day Lees records that he dies.

The linear marks done in ink and pencil and Lees’s insistent writing are worthy heirs to Vincent van Gogh’s letters to his brother, Theo. Despite being self-effacing in his paintings, Lees has always worn his heart on his sleeve.

Along with this attention to his present circumstances, paintings such as the panoramic “Hills of Home (Smaller Version)” (1997–2021) and “Couple (Winter)” (2020) indicate that Lees — who is in his late 70s — is the midst of a new phase in his career. In terms of color, he has gone from being a tonalist with a penchant for greens and browns that recall the moody seascapes of Albert Pinkham Ryder to a palette of reds, yellows, and violets. His recent color schemes are almost as shocking as Vermeer using a tube of bubblegum pink. Seen from an elevated viewpoint, the figure in the fenced yard, with his arms outstretched and his back to us, looks almost exhilarated, as his dogs run free in “Hills of Home (Smaller Version).” The drawing in the paint has become awkward, and shares something with the primitive Irish and English land- and seascape artists James Dixon and Alfred Wallis. Within the enclosed space of the yard, and of the painting, Lees seems to have found a way to let go of his melancholia, nostalgia, moodiness, and anger, all while staying true to his inner promptings.

John Lees: New Work continues at Betty Cuningham Gallery (15 Rivington Street, Manhattan) through May 22.

0 Commentaires