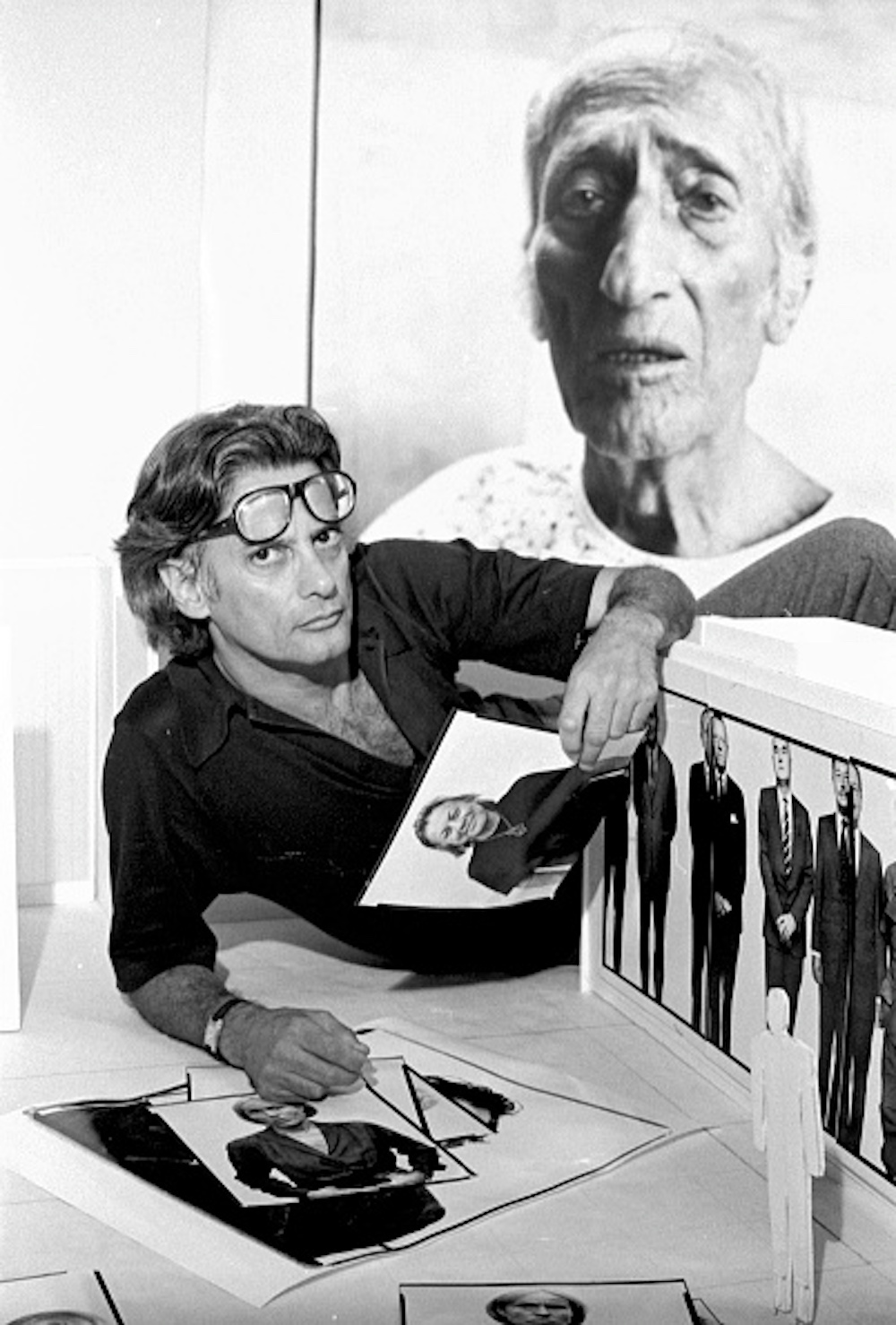

Richard Avedon’s last major exhibition before he died was at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was there on the closing day, January 5, 2003. Perusing this enormous retrospective of celebrity portraits, cowboys, and fashion models, I entered a separate room with a very different atmosphere. Here was a series of photographs of Avedon’s dying father, almost too personal for the public gaze. I felt like a voyeur but I was emotionally struck. Avedon was sharing his father’s last days with us. Why? Could the photographer not resist the rich visual portent of decay, tangling his emotions with his art production? Or was he motived by something else? I imagined that photography enabled Avedon to be more fully with his father as his health declined, to not turn away. These pictures revealed a son’s steadfast, insistent, unfiltered gaze.

His father had died in 1973. Avedon first showed this work in 1974 at the Museum of Modern Art. Jacob Israel Avedon: Photographed by Richard Avedon received mixed reviews. Avedon had been hospitalized during the show with an inflammation of the heart. A new biography by Philip Gefter, What Becomes a Legend Most (2020), recounts how he set a critical New York Times article on fire from his hospital bed then flushed it down the toilet. The objectionable review by Gene Thornton had concluded that the images “[…] seem to lack the classic, calm finality of truth.”

I left that room at the Met stunned. Whether the pictures held “the finality of truth,” I don’t know. But the space between a dying father, a camera lens, and a devoted but conflicted son imparted a kind of wisdom about life and art: Art is about the making of things and the processing of ideas but it is also about the courageous act of looking, of being present. Too often people look at things through a protective scrim of assumptions. We can become skilled at controlling the amount of emotional and human content we can bear. Avedon once said, “I think I photograph what I’m afraid of … things that I couldn’t deal with without the camera” (American Masters Series, 1996).

With new reverence, I returned to the exhibition’s other bodies of work, in which drifters, clowns, and coal miners sat alongside art luminaries like Andy Warhol and Francis Bacon and performers such as Janis Joplin or Tina Turner. These juxtapositions of humanity heightened the tenderness by exposing the shared vulnerability of all people. Avedon found people unequivocally interesting. He stepped nimbly in and out of social strata. The burnished faces of his cowboys are not so different from Samuel Beckett’s anguished countenance. I was so absorbed in the images that I initially did not notice the person standing next to me, who was also still and quiet. When I turned, I saw it was Avedon himself: short, fit, with his unmistakable mane of lush gray hair. He was there to take one more look on the last day of his show. First, I stared, and then I sputtered a few accolades. He thanked me sweetly and moved on.

A few months ago, I experienced the death of my own mother. For five days after she stopped eating, she lay in her nursing home bed, busy doing the work of dying. It’s not a simple thing for the body to shut down. Two windows graced her with light. I studied her face and hands, desperate to create imprints in my memory. My eyes roamed from her gorgeous white hair, now long and silky, to her face, almost unwrinkled at 99, to her arthritic hands, bony but elegant with polished nails. She was tiny, like a bird or child, only 70 pounds now, her legs like broken sticks bent toward her chest. I leaned in, snapped photos, tried to really see her. When my surveillance began to feel like an intense desire to consume, or make contact, I tried to meditate and simply be with my mother. People say you should talk to the dying to reassure them, but words felt too pedestrian for this profound space of transition.

While my mother was dying I turned to fabric to process my emotions. I cut strips of cloth, wrapped bundles with string, twined different cords and ropes, and made flowers from styrofoam grocery-store containers I had saved. My hands seemed to know what to do. When this object was completed, I hung it on the wall to assess it. I realized that I had unknowingly made a symbolic body, a portrait of sorts, of my mother, with her apron strings dangling. Her years of caring, tending, and mending were embodied in shreds of muslin and gingham, a scrappy heart in the center sadly tethered in kite string the way a three year old might repair an aorta. While her body was shutting down, perhaps I was psychically there, my fingers moving, spider-like, ritualistically, to create a new vessel for her as she relinquished flesh and heartbeat.

My mother died on February 9, at 11:15 a.m. I was not in the room. This fabric shroud hangs at my cottage. It is now my mother, her essence, far more tender and descriptive than the tiny box of ashes or a braided lock of hair I’ve saved. I want to think that in my own way, I was with her each day of her dying, my hands busy twining the infinite with her last breaths.

In Jewish tradition, the burial shroud, or tachrichim, is a white linen gown — the same for people of different backgrounds or means. It removes the deceased from superficial demarcations of culture or status. The shrouds are stitched by hand and have no buttons or zippers. Avedon routinely employed a white backdrop that separated the sitter from worldly vestiges. It almost seems as if his entire prior career was slowly building up to these photographs of his dying father. Through decades of preparation for the inevitable, he learned to frame the divide between presence and absence with two strobe lights and a Deardorff camera.

Avedon, who died the year after this retrospective at age 81, accomplished what all of us need to figure out, now more than ever: How do we hang on and let go at the same time?

0 Commentaires