Seven months after the Black Lives Matter protests in Salt Lake City, the Utah Museum of Fine Arts (UMFA) opened an exhibition Black Refractions featuring highlights from the Studio Museum in Harlem. Promotions for the show are accompanied with the slogan “Utah has never had an exhibition like this before.” While this may be a source of pride for the museum, the exhibition throws into vivid relief the shames of the state and its dominant religion.

The State of Utah is hardly a paragon of multiculturalism. Known as the “Beehive State,” it is home to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (or the Mormon or LDS Church), an organized religion started by Joseph Smith in 1830. With a Caucasian presidency and an overwhelmingly white clergy, some attribute the state’s lack of diversity to the religion and its tenets. Last year’s publication of “Mormonism and White Supremacy” by Joanna Brooks made great strides into unpacking these connections. Whenever I have tried to understand the situation, I am met with the response that to even ask about such things is racist, because Mormons love all god’s children and by extension, everyone here is colorblind.

* * *

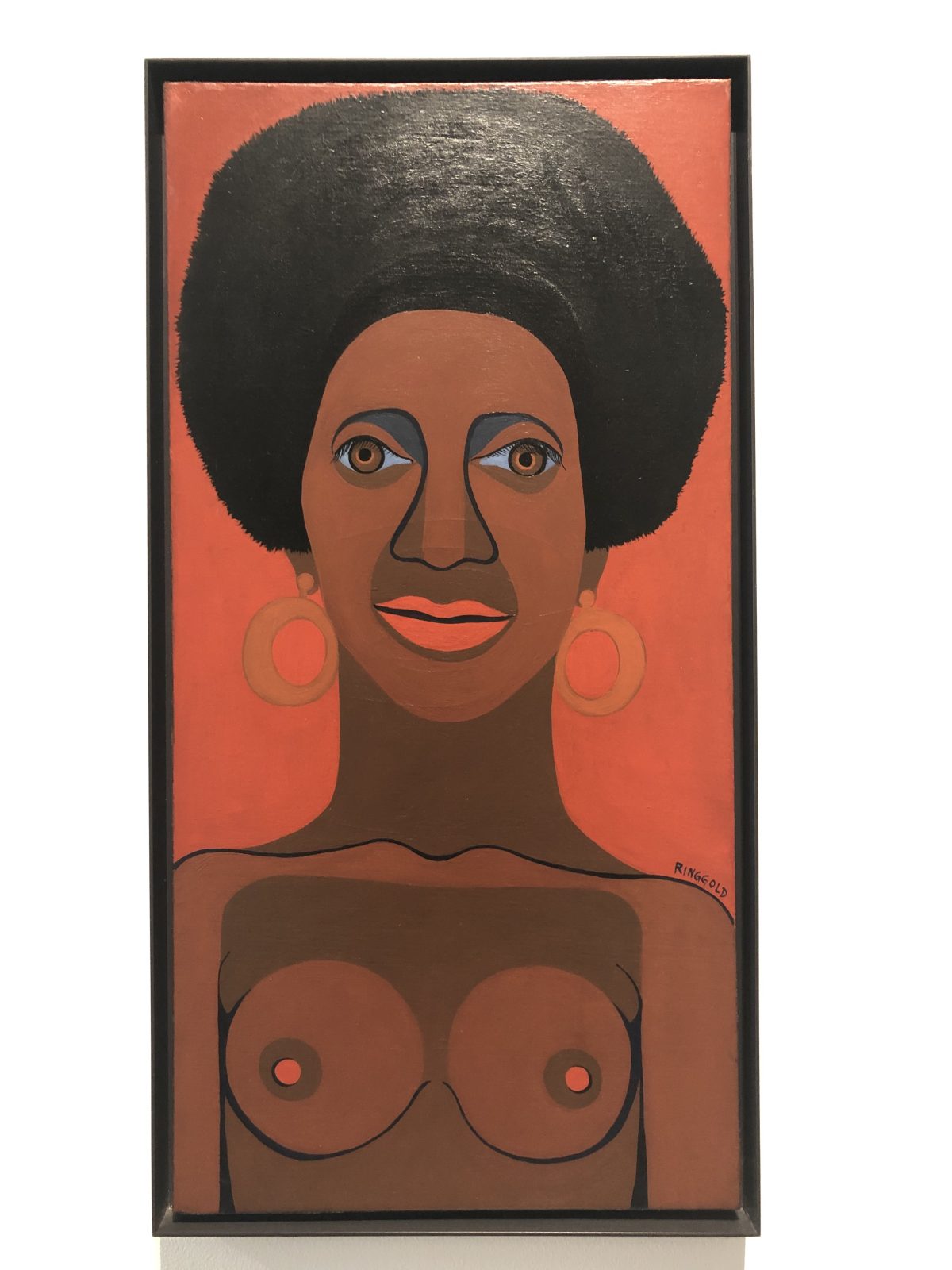

At the UMFA, over 100 works by 80 artists in the Black Refractions exhibition are augmented by a comprehensive educational program that partners with the University of Utah’s new Black Cultural Center opened in 2019 and the Tanner Humanities Center, opened in 1988. Inspired by the travelling exhibition below, the museum’s Modern and Contemporary gallery on the second floor has been rehung to include works from the permanent collection by Faith Ringgold, Jacob Lawrence and Willie Cole. While encouraging to see, their presence is tempered by the museum’s acquisition history documented on their website: Works by African, African-American, and other POC artists comprise a dismal five percent of total purchases made since 2017.

Front and center in the space is Chakaia Booker’s “Discarded Memories” from 2008. Comprising a corpulent knot of rubber tire strands, it stands at eye level. This leviathan leads our gaze into an adjoining gallery of “Arts of the Pacific” containing ancestor poles, shields, drums and masks from the Asmat culture of Papau New Guinea. A connecting gallery showcases the “Arts of Africa” from various peoples of the Congo.

Masks without shamans, crowns without kings, bowls without oils, the regalia stares out blankly. Drained of life and meaning, severed from their roots, they yearn for repatriation. Signage makes no mention of how the works came to be there. Were they pillaged and plundered as the spoils of war? Were they acquired by missionaries through “white savior” proselytizing still practiced by the church? Surely the owners of these artifacts would no sooner hand over their prized ritual objects than the Mormons would trade Joseph Smith’s own seer stones. In an essay from 2018, Elizabeth Gron Morton explains that one of the collectors, Owen D. Mort Jr. worked for the United States government as a USAID employee, from 1974 to 1982. During those eight years, he amassed an unfathomable 2000 objects from the Congo. While the objects may indeed have been fairly traded, only American imperialism and the ascendancy of the American dollar would explain such a colossal bounty.

I also consider how these “ethnographic” galleries stand in conjunction with works from the Studio Museum housed under the same roof, just one floor below, where the devastating legacies of exploitation are laid bare. There, they twist around Maren Hassinger’s “River” (2011); they tar the portraits by Titus Kaphar; they rust the surfaces of Leonardo Drew’s “Number 74” (1999). Seen in conjunction with the Pacific Island and African objects, they signify two sides of the same coin. Specifically, what would Salt Lake City’s Pacific Islander community have said? They may have valuable insights on the subject of this use of their own cultural heritage.

To understand the significance and sheer novelty of this exhibition, I looked more broadly to museum practices in the state of Utah as a whole. Like the mining museums, military museums and dinosaur museums, most museums in Utah preserve aspects of the Wild West. There are museums devoted to the stagecoach, the railroad, the trading post, the cowboy, and, of course, firearms. More Mormon history and settler culture are showcased in the Church History Museum, the Beehive House, and the recreation ground This is the Place Heritage Park. And then there are the 86 historic log cabins scattered around the state, maintained by the Daughters of Utah Pioneers.

How do the stories and histories of African Americans fit into this hegemony? Would Utah’s tastemakers be willing to name slaveholders living among the log cabin owners, risking a blight on Mormon perfectionism? Should the role of slaves be acknowledged in the construction of Deseret or Zion? Nowhere do these dynamics come into sharper focus than in the recent acquisition of a modest school bus by Lex Scott, founder of Utah’s BLM chapter, who will take her “Black History Museum” on the road, from schoolyard to schoolyard.

To be sure, the UMFA should be commended for acknowledging racial bias and for pledging to be an “anti-racist institution.” For the past decade, the museum has made gentle inroads into the state’s parochialism: Their ACME Lab and Salt series has brought in artists from around the world. Yet, when the director quips that “Utah has never had an exhibition like this before” I wonder why on earth not and what took them so long? Perhaps the exhibition is too little, too late? Located on the university campus, I also wonder how its lessons and aesthetics can percolate beyond the ivory towers to confront racism in the community at large? Could the UMFA, self-styled as a “regional leader” spearhead workshops to help Utah institutions divest of their white supremacy?

More generally, will a purported new museum of Utah art and history currently on hold, venture beyond the familiar tropes of the American West, to include stories that acknowledge black oppression and achievement? Where do the killings of Darrian Hunt, Elijah Smith, Bobby Duckworth, or Patrick Harmon belong? Will their stories be deemed “too negative” to be told in such a triumphalist society? Will Black Refractions be a one-off, temporary nod at the June protests, leaving Utahns to think that African Americans are part of the American patchwork who live elsewhere? Will Brigham Young University, the church’s flagship university, add to the six faculty of color, among a total of 1467 tenured professors? Could the church forbid its members from displaying the confederate flag, still seen around the state? Is it inconceivable that the LDS church, so celebrated for its organizational acumen, might initiate church trips for the brethren to see the exhibition and learn about the art and lives of their fellow Americans? What if they discover that many of the artists in Black Refractions have achieved levels of success and notoriety on the international art circuit that exceed that of any Utah artist, Mormon or otherwise? Could Utahns be magnanimous enough see this as a win for the country as a whole?

Of course, most agree that things in Utah are changing and nowadays it might be more accurate to say that Utah is a place where multiple narratives intersect. It may however take more than one travelling art exhibition to fulfill the hopes and dreams of this promised land.

0 Commentaires